Do The Write Thing

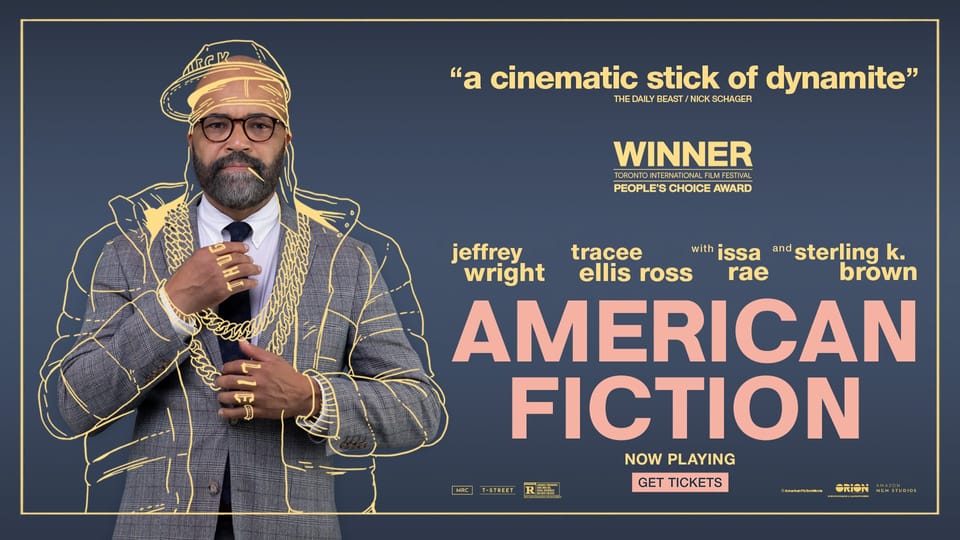

Ahoy, readers! This week's new release is not quite so new, as it took a month to make it my way. It's a definite Oscar contender, though, and Jeffrey Wright is seemingly incapable of giving a bad performance, so it was a natural pick.

It’s not often that a movie succeeds by failing to deliver on what it promises, but that’s basically how American Fiction shakes out. The trailers advertised a somewhat pandering send-up of white obliviousness; what we actually get is both less than that, and more. The political humor is the movie’s weakest element, but is also much less important than expected. The movie is much more of a character study and dramedy, bolstered by a great supporting cast, and all the better for it.

The story, set in the present day, concerns novelist Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright), a black author of literary fiction with little patience for priggishness about the subject of race. Monk’s agent Arthur (John Ortiz) is unable to find a publisher for his latest novel, a retelling of Aeschylus’ The Persians, which adds fuel to his contempt for fellow black writer Sinatra Golden (Issa Rae). Her crass potboiler We’s Lives In Da Ghetto is a critical sensation for its so-called honesty, which Monk sees as pandering to white liberal guilt. On a trip home Monk begins to reconnect with his sister Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), the family maid Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor), and his mother Agnes (Leslie Uggams), who is beginning to show signs of Alzheimer’s. When Agnes's condition worsens Monk finds himself needing money to pay for her care, and so he ends up selling a scabrous ghetto fiction parody he wrote as an angry joke titled My Pafology to a top-dollar publisher, only to find he has to keep up the pretense of the hardened thug nom de plume he’s adopted, Stagg R. Leigh.

There is much more to the story—including Monk’s estranged gay brother Cliff (Sterling K. Brown), Monk’s budding romance with his neighbor Coraline (Erika Alexander), and a literary award for which he agrees to be a judge—than could be fit into that synopsis without getting into major spoiler territory. It is in fact not until nearly halfway through the film that the Stagg R. Leigh plot kicks off, and even once it does, it never becomes the focus.

Instead writer-director Cord Jefferson (directing his first feature after a decade of TV that includes The Good Place and HBO's Watchmen) uses the literary con as a device to develop the other themes and subplots—namely the cravenness of the publishing industry and, especially, the way Monk’s erudite condescension tends to push others away. This will disappoint those who came to the movie based on its premise, but it worked for me due to the excellent character work. Jeffrey Wright plays Monk with an agreeably prickly impatience as a baseline, but he gets a wide emotional range—righteous anger, brotherly affection, regret at missed opportunities, cautious romanticism. His scene partners are at the same level and are collectively the most important element in the movie's success. John Ortiz gets the funniest material, playing at both sides of the Monk/Stagg R. Leigh deception. Tracee Ellis Ross’s portrayal of someone who’s so used to her brother’s bullshit she can needle him about it is so good and lived-in, it’s disappointing that we do not get more of her. As written Cliff is a minefield of a character, a selfish gay hedonist too busy partying on drugs to care about anything or anyone else, but Sterling K. Brown deftly manages to locate the hurt behind the bad behavior. The whole cast is like that, taking roles that are sometimes under-written and giving them personality that makes them very enjoyable company.

The foregrounding of the family drama makes this perhaps a bad adaptation; I have not read the Percival Everett source novel Erasure, but given Everett’s penchant for heady postmodernism and the story's clear autobiographical touches (Everett too has written several novels reimagining ancient Greek classics), it strikes me as being much more weird than the movie allows, something along the lines of Charlie Kaufman’s script for Adaptation but with the neurosis turned outward. Some of the literary aspects are retained—the dialogue can be verbose in a way that works better for prose than speech, and there are stabs at metafiction toward the end—but Jefferson’s direction favors the warmer character-driven material, with soft visuals, naturalistic acting, and an easy breezy jazz score from Laura Karpman.

The political humor loses some of its edge and energy because of this relaxed mood, but this is to the film's benefit because its politics are, frankly, kind of bullshit. Essentially the movie pitches itself as a didactic social justice-informed satire of white people not caring about diversity, when it is in actuality a didactic anti-social justice satire of white liberals not caring about quality black literature because they’re too busy pretending to care about diversity. It’s hard to disentangle the perspective of the source material from the post-George Floyd environment in which the movie was made, much less do so succinctly; suffice to say the political satire did very little for me. The satire of the publishing industry, which I do think is separate from the politics, is much more successful for its specificity. (The debate over whether or not to read manuscripts in their entirety when judging them is so real it hurts.)

One wonders if the material would have been better handled by someone with stronger political convictions and a penchant for the absurd like Boots Riley or Donald Glover. Yet Cord Jefferson has managed to find real humanity amid the caricatures, which only take up a quarter of the movie anyway, and so watching it feels like time well spent. The much-belabored Message of American Fiction is that black lives are more than just tragedy and prejudice, and the movie proves that. It just happens to do so whenever it isn’t visibly trying to prove it.

Member discussion