Metal Gear: Solid Start

Greetings, friends! As promised, here is the first installment of the Hideo Kojima retrospective, albeit at the end of the work week, not the actual week. I don't expect everyone is going to be interested in this tangent, so the next missive will probably be more strictly movie-focused. As much as I would like to have this series done in time for Death Stranding 2's release on June 26, I can already tell that's not going to happen, so I'm not going to rush it. A Kojima-less glow-up of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater comes out just two months later, which may be a more appropriate time to wrap it all up.

I. The Reality Is No Match For The Legend

Metal Gear

(dir. Hideo Kojima, 1987 for MSX2)

July 8, 2020 English transl. by Nekura_Hoka

"Hideo Kojima is a genius" is one of those 'it's true but you shouldn't say it' statements. The man's influence and creativity are undeniable, yet so to are his indulgences, especially as his fame has grown. He has been a superstar of the gaming world for going on thirty years, but in the past decade he has begun to expand his sphere of influence, first courting and casting Hollywood actors and directors, and now developing with hip studio A24 an adaptation of his 2019 game Death Stranding. Kojima may yet become a household name among what used to be called the general public, and they will almost certainly swallow the 'genius' line, as the hagiography documentary Hideo Kojima: Connecting Worlds already waits within their Hulu feeds to be fed to them. This is unfortunate.

Kojima may be brilliant, but he is also divisive, just as often vexing as amusing, and has been for nearly as long as he has been acclaimed. Some reasons are better than others, but he has not been universally beloved. Exploring why that is, is far more interesting than reflexive idol worship and offers substance to the empty gilded frame of 'genius.' In examining his body of directed work I hope to offer some necessary context, and what better lens than cinema? Kojima's body is "70% made of movies," and he is as yet the only game developer to have a Criterion Closet segment. The bridging of movies and games has been his project from the beginning.

There is in this the peril of nostalgia, the kudzu of judgment, a lovely little vine that strangles all it touches. I am hardly outside its reach, as I grew up on Kojima's Metal Gear Solid series. I want to cut away the overgrowth of hype and memory and see these works, and Kojima himself, for what they are: both derivative and original, inane and ingenious, authored and open. These are not constant states. The contradictions wax and wane over time, and the now-sixty-one-year-old elder statesman of video games is not the same person he was when he started working at Konami in 1986. Progression and regression, hand-in-hand: that's a very human story, and a compelling one.

II. Enfant Terrible

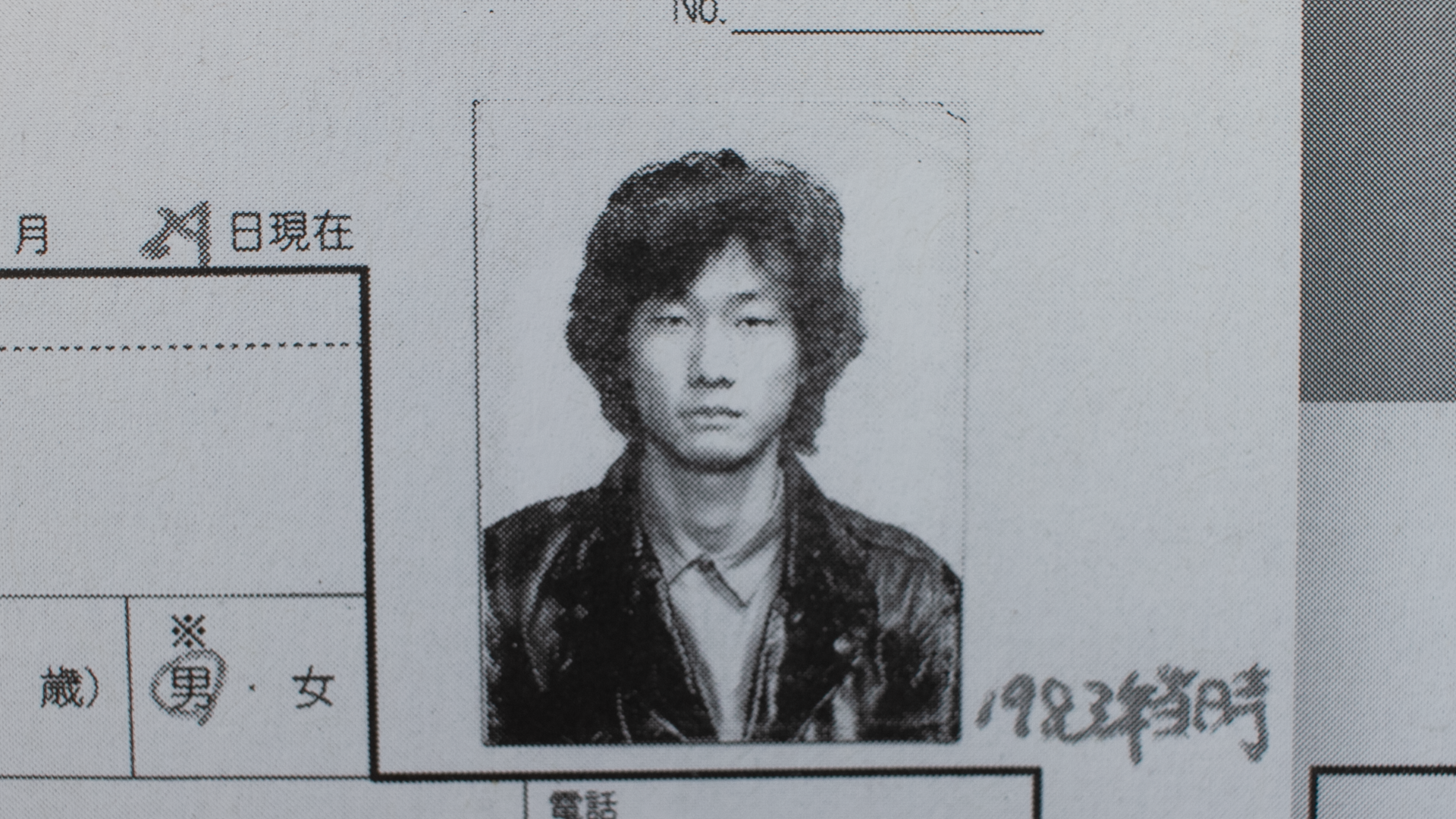

Kojima's story begins in August 24, 1963, when he was born in Tokyo. Growing up in Osaka, his father, Kingo Kojima, cultivated in him an ambivalence about war and a love of film, perhaps best summed up in him making the young Hideo watch the anti-war documentary Night and Fog. Filmgoing was a regular family pastime, with Kojima's parents not only allowing him to watch adult European movies with them but insisting he stay up until they were finished. When he was older he was given money to go see movies, on the condition that he discuss with them what he saw. Kingo passed away when Kojima was thirteen, a traumatic event that would shape many of his future works. His mother then went to work to support him and his two other siblings. (The death of Kojima's father and recurring patricidal motifs are the focus of a lot of discussions of his work, not the least by Kojima himself, but I'm more interested in the fact that his mother's name has not appeared in the public record at all.)

Kojima majored in economics in college but nursed dreams of becoming a filmmaker. Having made Super8 movies with his friends in his youth, as a young adult he tried his hand at writing novels in the hopes of getting enough acclaim to make the jump to film, and joined the games industry after failing to get a foothold in either. This was not uncommon, as he reminisced in a 2003 interview with game writer and author Oji Hiroi:

"It was fun, wasn't it? Everyone had these broken dreams...I know I had unfulfilled dreams about being in movies, or being in a band. Manga, too. Everyone was like that. We wanted to make names for ourselves. We were ready to show everyone what we could do. We had nothing to lose."

He also saw the creative potential of the medium, citing the expressiveness of Super Mario Bros., the branching narrative of The Portopia Serial Murder Case, and the detailed backstory of the war shooter Xevious. He was alone among his friends in seeing that potential, however, as games were looked down on as unserious and disreputable. It was this low status that led Kojima to specifically apply to Konami; they were the only games company listed on the Japanese stock market.

Less than two years passed between Kojima's hiring and the release of Metal Gear. Despite wanting to be part of the company's arcade or Nintendo Famicom division, he was assigned to the less powerful MSX, a Microsoft computer console with slots for multiple disks and cartridges that were played with a full keyboard rather than a controller or joystick. Kojima's only credit before Metal Gear was as a co-director of 1986's Penguin Adventure, a racing adventure game for which he reportedly only contributed some ideas but did not work on or manage. He was next attached to a wrestling game that became a platformer with the title Lost Warld (portmanteau of 'war' and 'world'), for which Kojima began crafting a story set on the Titanic involving a female "Masked Warrior." This was cancelled after six months for being too complicated for the MSX hardware to handle. It was not a promising start, but even here we can see the same mind at work that would go on to coin the term transfarring ('transferring' and 'sharing') in regards to a game that involves helping a group of Sandinistas destroy a nuclear-armed AI.

Following the cancellation of Lost Warld Kojima was handed a project that had bedeviled other Konami designers. The company wanted a war game similar to Capcom's arcade run-and-gun Commando, but as he had become acutely aware, the MSX hardware was limited and would not be able to display the many sprites necessary to convey a pitched battle. Kojima moreover objected to war and instead reimagined the project as the opposite, a stealth game where the player avoids combat. Company leadership was skeptical, but Kojima was eventually able to convince them to approve development. What eventually won them over was the exclamation mark that appears over enemies' heads when Snake is spotted, a piece of audiovisual feedback that would become a series signature.

III. It's Like Something Out Of My Hollywood Cinemas

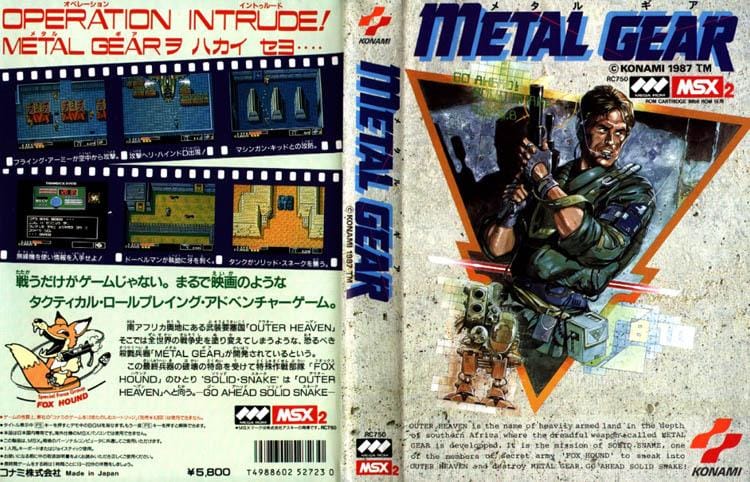

The game that resulted, originally with the generic title Intruder but renamed Metal Gear, put players in the role of Solid Snake, rookie operative of U.S. special forces unit FOXHOUND. Snake is sent by his commander Big Boss into a South African terrorist military base, Outer Heaven, after the unit has already sent in and lost contact with its best agent, Gray Fox. Snake infiltrates the base unarmed and has to scrounge up weapons and tools, rescue Fox and other hostages, and eventually destroy Outer Heaven's secret weapon Metal Gear, a bipedal tank capable of launching a nuclear warhead.

It's a scenario that wouldn't have been out of place among the military action movies of 1980s Hollywood, though Metal Gear would have hardly been alone on that front. Many contemporary titles were pastiches of known movies or characters: Konami's own Castlevania staked out its own territory in Dracula fiction, and Universal Studios unsuccessfully sued Nintendo in 1982 for infringing on their King Kong copyright with its game Donkey Kong. Taito's Operation Wolf, released the same year as Metal Gear, pulls from the same post-Rambo and -Commando iconography of a lone soldier going behind enemy lines to rescue hostages, albeit much more violently.

Although Metal Gear's military aesthetic recalls a Stalone or Schwarzenegger flick, it pulls from a much wider variety of inspirations. Its stealth ethos Kojima attributed to The Great Escape, though much of its attitude is lifted from John Carpenter's Escape From New York. The name of that movie's hero, Snake Pliskin, and his cigarette-smoking solo rescue operator archetype, were transplanted to Solid Snake wholesale. (Kojima took "Solid" from the song "Solid State Survivor" by Japanese electronic group Yellow Magic Orchestra.) Pliskin's eyepatch is given to Big Boss, and so instead of Kurt Russell Snake's appearance on the original box art is ripped directly off of a publicity still of Michael Biehn as Kyle Reese in The Terminator. One of the bosses, Coward Duck, owes his name to the comic adaptation boondoggle Howard the Duck as well as the foe's gameplay gimmick of using hostages as human shields. The Bruce Lee film The Big Boss is the namesake of the FOXHOUND commander. Kojima fit his homages in where he could.

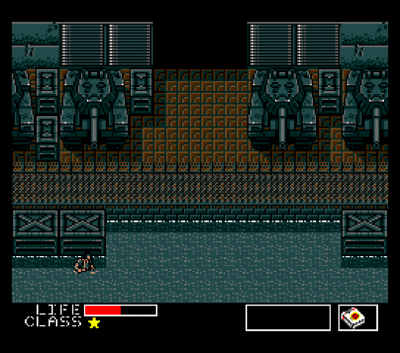

There were, of course, not very many places he could do so. The presentation is a birds-eye view, providing the player a wide view of their environment at the expense of character detail. These characters will occasionally give a few lines of flavor text, a thank-you and maybe a hint from a hostage, boasts from bosses with names like Machinegun Kid and Shoot Gunner, but little else. There is a radio that Snake can use to contact Big Boss and members of an ill-defined resistance group within Outer Heaven, but only Snake has an avatar on the 'Transceiver' screen; the others exist only as short text messages, with their character art and most of the visual film tributes confined to extrinsic elements like the game's manual. The radio calls have some character to them, but they are short-lived and inconsistent, often failing to even provide the guidance that is their main purpose.

IV. Syntactical Espionage Actions

It falls then to the language of games for Kojima to convey his story, and the vocabulary here is limited. While Metal Gear provides a good mix of tools and obstacles (albeit spread across a map that eventually gets tedious to backtrack), the player is still essentially either moving, punching, shooting, using an item, or calling on the radio. Only very occasionally is gameplay interrupted for a scene to play out, more or less in the intro and ending, and then a point early on where Snake has to be 'captured' and put in a cell next to Gray Fox. There is also a sequence on a rooftop where an alert is automatically triggered and the player has to fight their way through. This is supposed to convey a kind of action hero perseverence but is instead just aggravating, because of how it goes against the game's basic design.

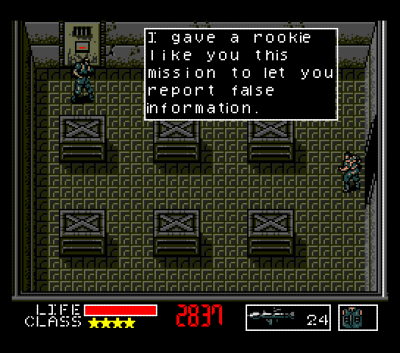

Although some of Metal Gear's frustrating difficulty can be chalked up to its 1980s design and Kojima's inexperience, there is some deliberate, in-universe justification. Big Boss is conspicuously not helpful most of the time, conveniently "forgetting" to tell you about items you will need. By the end he is feeding you straight-up misinformation, directing you to a truck that sends you back to the beginning of the base and into a room with a pit in which you can easily fall to your death. In the final stretch you get cryptic warnings about the leader of Outer Heaven, and after destroying Metal Gear TX-55 you come face-to-face with the terrorist leader—Big Boss.

The twist is rudimentary and would have deeply stupid ramifications for the series in the future, but here in its original context it is effective in expressively leveraging the game's limited systems. We know now that Kojima likes messing with the player and their expectations; this can occur with sudden fourth-wall breaks, as when Big Boss orders you to abort the mission and turn off the MSX (a line repurposed to even greater effect in Metal Gear Solid 2 over a decade later), but it can also be with the gleeful trickery of Big Boss' misdirection. Even after he dies and you have to escape Outer Heaven before the base self-destructs, you are presented with three ladders to climb, two of them leading to dead ends, one last trap for when the player thinks they would be done. Beyond all the names and tropes that would become endemic to the Metal Gear series, it's this, the desire to fake the player out and provide the satisfaction at having been played like a damn fiddle, that marks this as the first Hideo Kojima game.

V. You're Pretty Good

The action movie pastiche ends as it must: with an explosion, several even, as Snake makes his escape from Outer Heaven. He makes a final radio call, declaring victory and his intent to return home, not unlike Ripley at the end of Alien. Then, in one more bit of repurposing the game's elements, the transceiver switches to a news station, 'Radio KNK,' reporting on an earthquake that hit near 'Galsburg, South Africa,' that then segueways into the game's credits. Of course Kojima cannot resist one last twist, a post-credits stinger indicating Big Boss is not dead and will have his revenge. It is but one of many, many elements that would become series hallmarks.

Metal Gear's aged design makes it mostly a historical curiosity today, but its fundamentals were strong enough to for it to be a success in its own time. Even an inexplicably bastardized Nintendo port for the American market did well enough to garner an unofficial but very important sequel. As an attempt at channeling cinema Metal Gear is modest, barely a story, and mostly a framework on which to hang the gameplay. Yet the essence of its scenario—a solo infiltration, betrayal by the player's superiors, destroying a nuclear mech—along with the sometimes nonsensical but evocative names, would become a template for a medium-defining series. In the meantime its brisk sales afforded Hideo Kojima greater resources and autonomy at Konami going forward. His authorial voice and aspirations, here only fleetingly glimpsed, would soon be on full display.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion