Final Fantasy Rewind: Cracked Crystals

Greetings and happy end of February! This week I'm going to do something a little different. I've an ongoing interest in how video games and film intersect, and Final Fantasy has been at that crucible for nearly three decades. Its next installment, Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, comes out this week, so it seemed appropriate to revisit the several infamous attempts at turning the increasingly cinematic games into proper cinema. I have so much to say about these that I'm breaking up this retrospective to give each movie, four in all, its own dedicated entry. The first one up was not released theatrically, but it's a useful introduction to the topic. It is also so obscure and so unbelievably nuts that sharing it is practically a moral imperative.

Final Fantasy: Legend of the Crystals

(1994, dir. Rintaro)

Video game adaptations all struggle with how to translate the interactivity and gameplay systems of the medium into a linear narrative. Many of them already come with narratives which bring challenges of their own. Super Mario Bros. had essentially no real plot to adapt, while The Last of Us was already so complete as a tightly-scripted story which the gameplay served to immerse a player in, that a prestige TV show seemed redundant. The quandry of the Final Fantasy series of Japanese role-playing games (JRPGs) has been that there is entirely too much story to adapt. These titles could take 30 hours to complete even in the early 1990s, and they only get longer from theire; how could this possibly be adapted to a two hour feature?

The series had narrative aspirations from the beginning. The original Final Fantasy, developed for the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1987, had the player controlling a party of four Warriors of Light charged with rescuing a princess from a dark night. This was a stock framework for games of the time—contemporaneous titles like Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda were also about saving imperiled princesses, but they never went beyond that. In Final Fantasy the rescue is only the beginning of a much bigger quest. It was primitive, consisting of going town to town and getting a new task, harnessing the power of four elemental crystals, defeating four elemental fiends, and a nearly incoherent climax involving a time loop. The four party members are all nonentities defined only by their fantasy classes, or 'jobs,' selected by the player (thief, black mage, white mage, knight, monk) for the skills they had in battle. Nonetheless Final Fantasy was a statement of intent for creating a grand fantasy narrative.

Subsequent games would build on these narrative and gameplay foundations. Final Fantasy II had the player controlling a party of named characters with defined roles in a story of a resistance against a growing imperial power, and the first entry for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, 1992's Final Fantasy IV (released in the U.S. as Final Fantasy II), gave its characters classes unique to them and their personality, and fleshed them out with motivations and full arcs; they undergo redemption, overcome fear and distrust, are consumed by revenge. All of this was done with creative use of crude visual storytelling tools: text boxes and character sprites typically only 16x16 pixels, and brilliantly economical but evocative music using the 8- and 16-bit sound chips of the consoles the games were made for. The storytelling was still simple, but it was begging for a bigger canvas.

The idea of a Final Fantasy anime had been pitched early on, but didn't take shape until the involvement of 'Rintaro' Shigeyuki Hayashi, began his career working on Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion and had already directed episodes of the anime adaptation of Final Fantasy competitor Dragon Quest. According to Sakaguchi,

Around the time of the game II or III... about five to six years ago, there was talk of making an anime of FF, but it didn't seem like they were going to make a good anime.... If I was going to do it anyway, I wanted it to be something memorable. So when I heard that Rin[taro] was going to do it, I thought, "I'm glad I waited." I had been waiting until VI to have you [Rintaro] do it. I guess sometimes patience is a virtue.

The result was not a traditional movie but an Original Video Animation (OVA), an anime movie or show that goes straight to video without being shown in theaters or broadcast on TV. It was produced not by Square but anime studio Madhouse, which would go on to produce Ninja Scroll and Perfect Blue among many other seminal anime.

The story is a sequel to Final Fantasy V, then the most recent title in the series. Two hundred years after the restoration of the four elemental crystals, the world (not previously named but here bafflingly referred to as 'Planet R') is threatened once more. At first fighting amongst themselves before uniting to protect the crystals are biker punk Prettz; aspiring summoner Linally, a descendant of one of the game's playable characters; Valkus, a general of Tycoon's airship navy; and Rouge, a leader of an all-women group of air pirates. They are aided by the spirit of Mid, the grandson of secondary character Cid from the source game, who was an adult there but is here a child. The force coveting the crystals is eventually revealed to be a demonic extraterrestrial presence, Deathgyunos, who will use their power to make himself god of the universe. It's an uninspired premise, essentially a remix and rehash of the plot of the game, which was simplified to make room for a far deeper version of the character jobs systems seen in FFI and III. (It is still one of the thinnest plots in the series, with a big bad named Exdeath who is literally an evil tree.)

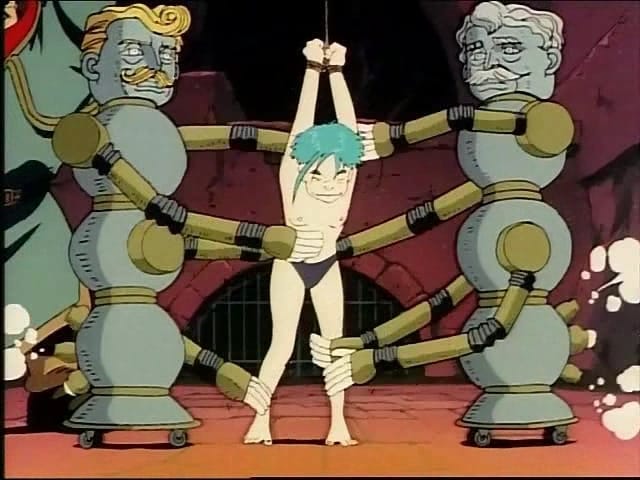

This would suggest a by-the-numbers bargain-bin kids fantasy, but that could not be farther from the truth. The generic plot outline is effectively a Trojan Horse for an utterly batshit insane execution. At one point Linally is tasked with protecting the Wind Crystal, which she houses inside her. So far, so standard adventure. But periodically the crystal lights up her panties—which are flashed toward the viewer so many times I lost count—and at one point it shoots a beam of light out of her butt, which serves to open the path to a mystic tower. There is so much like this. Little Mid is not just a projected spirit; he's a ghost, and we see him as he's killed by a laser beam to the heart by Deathgyunos, who then goes on to steal Cid's brain and uses it gain the knowledge of the crystals. This child ghost says, "I was killed without getting Grandpa's brain back from him," with utter sincerity. Rouge's pirate crew are all burly women in asymmetrical leather gear and goggles who call her "sir." Deathgyunos—who somehow has a worse name than Exdeath—is killed with a giant energy beam, but it's made up of chocobos, Final Fantasy's giant yellow bird steed mascot, who in this rendition have no feathers. Details like this pop up with bewildering frequency on the order of every few minutes. Sakaguchi absolutely got his wish that the anime be memorable.

Which is good because Legend of the Crystals is otherwise pretty bad. The character animation is decent, but the backgrounds tend to be low detail. Character designs are a hodgepodge of influences. Prettz, with his katana, goggles, and motorcycle, has a steampunk look, while Linally and her grandfather have traditional Chinese robes and yin-yang iconography. Deathgyunos looks like the All Your Base Are Belong To Us meme until he takes on his gnarly final boss battle form, which is like a monstrous cyborg version of one of Tetsuo's fleshier malformations in Akira. Tycoon's Queen Lenna looks like Shi'ar Empress Lilandra from the X-Men comics, and indeed a huge part of the overall aesthetic is 80s space fantasy, the airships all looking like they came out of Star Wars. The world is a barren waste that owes a debt to Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, but also Tycoon Castle is literally the Taj Mahal. There is a dizzying lack of consistency.

The games also have eclectic tones and influences—the back end of Final Fantasy IV involved battling inside a mechanical giant and flying to the moon in a space ship shaped like a whale—but there was usually some kind of context given and room for it all to breathe. Everything here changes so frequently, is packed so tightly, that it never feels like a coherent world. But then that was the goal: condense the hallmarks of the marathon games into a two hour package. It's there if you look—the ragtag group of heroes, the crystals, chocobos, a climax in which our heroes attack and dethrone god. There are even snatches of Nobuo Uematsu's wonderful music. Yet crucially missing is any sense of wonder and exploration, and any characters to get attached to. There's too much shrill comedy and distractingly horny panty shots for that.

Final Fantasy: Legend of the Crystals was released in Japan on VHS and laserdisc in 30 minute installments from March to July 1994. It was released in the U.S. in 1997 in the wake of Final Fantasy VII's meteoric success, before FFV itself was even localized. It was never released on DVD, though it just last week got an HD broadcast in Japan. It was not without impact: sexy sky pirate Rouge was a direct inspiration for sexy sky pirate Red Monika in Joe Madureira's steampunk fantasy comic Battle Chasers, launched in 1998. But it is basically an obscure curiosity. The same cannot be said of the next attempt at a Final Fantasy movie.

Thanks to Mirrorfalls for help with the V-Jump Japanese translation.

Member discussion