Final Fantasy Rewind: Dilly Dally Shill

Hello! This week's entry is the second-to-last of the Final Fantasy retrospective, and for my money the worst of them all. It's a definite Rubicon moment when it comes to that particular franchise, and feels like a very early sign of how pop culture franchises would begin to operate a decade later. For what it's worth the FFVII remake games are much more thoughtful and experimental in how they play with the material, and I have to think some of that is from lessons learned here and in the other sequel media.

Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children Complete

(2005, dir. Tetsuya Nomura)

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within was a disaster, but so mighty was Squaresoft at the height of its powers that the damage was mitigated by the Japanese release of Final Fantasy X on the Playstation 2 only weeks later, and in the west later that year. FFX did well enough to stabilize Square's finances and garner a sequel, the awkwardly title Final Fantasy X-2 in 2003, a first for what was then an anthology series. That same year Square concluded their merger with rival Enix, and the newly christened Square Enix immediately set out to follow X-2's success by fully exploiting the popularity of their flagship series.

To do so they would employ a new 'polymorphic content' model. Rather than 'the traditional model of secondary content,' of first making something people like and building on it, there would be a central idea from which multiple products—games, movies, TV series, toys—would be produced concurrently, to be purchased concurrently. That audiences would be interested in that central idea sight unseen was just taken as given.

The first steps of polymorphic content production would be with an idea that had already proven its appeal: Final Fantasy VII, the game that changed Square and the games industry at large. Announced in 2003, the Compilation of Final Fantasy VII, would be a variety of ancillary media that would extend and fill in the gaps in the already 30-hour long game's story. The first release was a mobile prequel game that year, but the real kicker would be a CG-animated feature film directed by the game's character designer Tetsuya Nomura and produced by its director Yoshinori Kitase, Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children. It would fill in the biggest narrative gap of all: the game's ending.

This is a problem. Final Fantasy VII's climaxes with a potentially world-shattering meteor strike on an industrial city that is being held at bay by magic and the actual physical lifeforce of the planet—and then cuts away before we can see the outcome; a post-credits scene set 500 years later shows the site of the impact now overgrown with lush vegetation. Though the sound of children's laughter is heard, no humans are seen. Did our party of characters survive? Did anybody? The game doesn't say, instead leaving it up to interpretation. It's ambiguous. Of course, gamers hated it.

It's hard to gauge just how many fans wanted definitive answers, but the sentiment was there, and apparently not just among players. The movie began life as a brief in-house demo from Visual Works, Square's in-house CG animation studio, showing a love letter being passed between kids that paid off two of the game's main characters' will-they-won't-they dynamic. This excited a lot of the team, and so a follow-up project was quickly greenlit and expanded to feature-length. The result, the official ending to the ending of Final Fantasy VII,[1] is a dispiriting example of creators misunderstanding their own work.

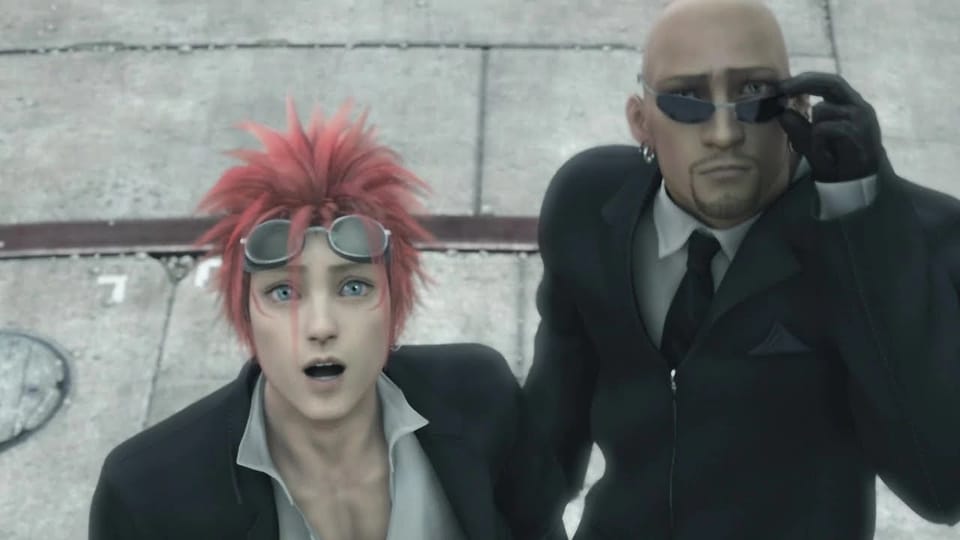

The movie starts where the game wrapped up, recreating the post-credits scene before cutting back to "498 years earlier," two years after the game's climax. Humans live on in the Midgar ruins, but people are falling ill with a sickness called Geostigma, thought to be the Planet's revenge on humanity for its destructive behavior.[2] The game's protagonist Cloud Strife is brooding over the death of his comrade Aerith and his history of... it really doesn't matter. Final Fantasy VII is an excellent if somewhat overrated game, but describing its plot elements (including false memories and genetic experimentation) makes one sound like a maniac. All one really needs to know about Advent Children is that Cloud's moping is interrupted by three petulant silver-haired anime boys want to find a magic Macguffin that will bring back the game's iconic bad guy, and stopping him will also stop said moping.

It's basically an excuse to shuffle characters around to locations from the game with much more detailed 3D animation than was possible in 1997 while speed running its story beats. There's only one new character, a sick kid, while several dead characters are trotted out, and all but one or two of the (English-language) voice actors sound bored with their inane dialogue. As storytelling it is just dire wheelspinning for ages.

Then in the last 45 minutes it becomes a series of escalating frenetic action setpieces: a team battle against a giant summoned dragon, Bahamut SIN; a motorcycle chase-and-swordfight; and a duel with big bad Sephiroth. They are deliriously staged, flouting all rules of gravity and the durability of the human body. There are some nice touches too, like a moment where the entire team from the game takes turns to throw Cloud into the air to deliver a killing blow. Cloud also now has a giant sword that is Voltroned from six other swords, which is agreeably daft.

It's quite the sugar rush, but that's all it is. Square Enix would spend the next decade-and-a-half chasing the spectacle seen here and trying to recreate it in the traditionally turn-based battles of the Final Fantasy games, which is just as well; there isn't any sense of progression or logic to the fights, so it makes more sense to imagine that every punch and sword strike has numbers coming off the characters, and that the fights end because one of the combatants reached zero HP.

The fight scenes do highlight how much the animation has improved since The Spirits Within. The character designs have backed away from uncanny valley photorealism and toward a kind of realistic anime stylization that is much less stiff. The imaginative locales are well-represented, particularly the the luminescent flora of the City of the Ancients. The movie delivers on its spectacle. The visuals suffer, however, from the movie's original render resolution, some 480p, only later re-rendered to 4K, with some variability in the detail now more visible. Which is unfortunate, as it's the one thing the movie has going for it beyond the original game's composer Nobuo Uematsu doing some trash-metal remixes of his iconic score.

'Trashy remix' is basically where this project lives. It's fan service and can certainly be enjoyed as such. But Final Fantasy VII is one of the canonical Greatest Games Ever Made, cited to make the case for them as a legitimate storytelling medium, capable of conveying artistic intention and emotion. The death of Aerith is the moment that's always cited, but the real deal is the ending's willingness to trust the player to come to their own conclusions. That the ending was ever so controversial is an indictment, both of gamer literacy and of Square Enix, who felt the evocative sound of children's laughter needed to be made so cloyingly literal. The movie ends with a bunch of kids baptizing Cloud and frolicking in a pool, which is about as appropriate as if The Sopranos had ended with Tony hugging "those goddamned ducks."

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within was at least an ambitious failure, with Hironobu Sakaguchi's reach exceeding his grasp.[3] Fantasy VII: Advent Children is a success, but only in the most mercenary sense. Yet the movie and the Compilation of Final Fantasy VII project were in their own way forward-thinking. Impenetrable mega-franchises, pandering nostalgia sequels, weightless CG spectacle, capital-C Content—this is the IP-driven pop cultural landscape we live in today, and here was Square Enix, all the way back in 2005, turning their keystone series into a multimedia, multi-franchise engine.

There were concerns at the time within and without that Square Enix had milked their golden goose. But like all such schemes, it worked for a time. Advent Children and the multitude of spinoff media sold well enough, and whatever damage they did to the brand was not enough to temper enthusiasm for a trilogy of modernized Final Fantasy VII remakes that began releasing in 2020. If anything the appetite was even greater becausea of what came after the Compilation. For, having established the 'polymorphic content' model with an old property, Square would go on to try it out on something new. The results would be legendary.

Except it's still not the end, as one character, Vincent, received a game of his own that takes place after Advent Children. ↩︎

Which would be a great idea if the movie was actually going to show why we don't see any humans in the future, which it isn't. ↩︎

It belatedly strikes me that The Spirits Within's conceptual mix of science and spiritualism is both very eastern and very anime, and a lot of the script's creaky cliches and awkward over-explanation are a product of filtering that through the sensibility of western Hollywood screenwriters with no frame of reference for e.g. a cycle of souls and rebirth. ↩︎

Member discussion