Game Overload

Greetings, friends. The intersection of video games and cinema is an ongoing interest of mine, and so last month I watched several new and recent films, the documentary Break the Game, French indie drama Eat the Night, and the corporate juggernaut of A Minecraft Movie. Each provides different angles on the ways games fit into our lives. They are not often good ways, but they are true, even if, in the case of Minecraft, they are in ways they did not intend.

I Stream, You Scream

Break the Game

(dir. Jane Wagner, 2025)

It took modern homo sapiens two million years to evolve its capacity for communication, and less than two decades for social media to break it. Technology has been lowering the distance between people since the invention of the telephone in the late 1800s, but the connection of billions around the world has not only accelerated the speed of life but overloaded it. Nowhere is this more true than with streamers, most typically found on Twitch. The most successful have an audience of tens of thousands, but it is a two-way interaction; innumerable viewers from around the globe are able to respond and interact and affect the course of a given broadcast with the intimacy of a live, in-person performance. Humans are not built to handle this much interaction in general, even less so when those interactions become hostile. Dealing with an online hate campaign is the hook of Break the Game, which premiered on Twitch on April 21, after original host PBS pushed back its broadcast due to fear of government retaliation. Yet mass harassment ultimately feels like a symptom of the broader attention economy and its agnostic attitude toward antisocial behavior. The incentive structures of the modern internet make the praise of an audience nearly as perilous as its venom.

The subject of the documentary is Narcissa Wright, née Cosmo Wright, who first came to prominence as a speedrunner of the Legend of Zelda games, racking up world records for beating Ocarina of Time and The Wind Waker and her streams being watched by 18,000 viewers at her peak. Wright came out as transgender in November 2015 and immediately saw a collapse in viewers and subscribers and a wave of transphobic harassment. We enter the story as she tries to rebuild her audience. She is taken by the release of 2017's The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, and thinks chasing after the speedrunning record is the key to showing up the haters and getting back to the top of Twitch. "I want to be idolized by my viewers," she says. "Twenty-thousand viewers or bust." That essentially leaves no room for failure, and plenty of room for rubberneckers and worse to fill the void, especially as she struggles at times to break even twenty viewers.

The majority of the doc is assembled from Wright's video archives, chats and all, tempest-tossing the audience among the stream's shifting tides. Twitch is already a sensory DDOS attack, with a streamer's game and camera feeds surrounded by chat, ads, suggested follows, and loud subscriber pop-ups, and director Jane Wagner augments this with a hyperactive Monster energy editing flow, channeling for us the subjective experience of watching a viewer count tick up or down, or a chat explode with hype or calls for suicide. Adding variety are some lively retro game pixel art animated sequences by Pat Ackerman and Emily Wolver which put an expressionist gloss on Wright's trials and mindset. It's the most comprehensive portrayal yet of a sector that in just over a decade has become a hub of youth culture.

At the risk of sounding hopelessly out of touch: this is a deeply unhealthy development. Success on video streaming sites like Twitch demands more from a performer than any other kind of social media platform. Streamers are not just playing a game, often at expert levels requiring immense concentration, they are also acting as a host for their viewers, putting on a show and cultivating a parasocial intimacy with them. Keeping an audience means doing this on a consistent basis and for hours-long stretches. It's no surprise then that Wright's on- and off-screen lives become inseparable. Brushing her teeth, making her bed, sleeping in it, the digital panopticon sees all, including an incredibly upsetting mental health episode that becomes meme fodder for trolls and bigots and also turbocharges Wright's viewer count. A brief scene early on where Wright, on camera, looks herself up on YouTube and Twitch and finds a seemingly endless feed of gleefully malicious videos reacting to her videos, encapsulates the grim orobouros of the content industrial complex.

There are positive connections made through this. The most important of them is fellow trans streamer d_gurl, with whom Wright begins a romantic relationship. d_gurl is even-keeled throughout, sensibly telling Wright when she starts soliciting mental health advice from her viewers to log the hell off and talk to an actual therapist. She presents as a best-case streamer example, having boundaries and an outside life and interests. d_gurl pulls Wright back from the edge, facilitating a late pivot in the documentary's story and presentation, to life and footage beyond the Twitch platform. It is a genuine relief when it happens, to see footage that wasn't originally live-streamed and created for online consumption. It culminates in a drone shot atop a mountain that recreates the opening reveal shot of Hyrule in Breath of the Wild, neatly bringing the story full circle.

That this happy ending is only achieved by foreswearing the social Skinner box of Twitch is a damning indictment. Streamer trihex, who hosted the premiere, was candid in the talkback with Jane Wagner about his own mental health struggles, that streaming is "literally doing Covid quarantine." The irony that Break the Game premiered on Twitch was not lost on anyone, with trihex noting how surreal it is to watch "Twitch chat reacting to Twitch chat." The premiere, and the Q&A and roundtable discussion about online abuse that followed, shows the streamer format isn't wholly without merit; nobody involved in the documentary would have made it if they thought streaming was irredeemably broken. But these instances of thoughtful interaction and sustainable living occur in spite of its incentive structure. Break the Game's unvarnished look at what Twitch does to people who try to make a career on it—or any social media platform—raises serious questions about its net effect on society. Twitch doesn't even benefit its owners; the rest of us can hardly fare much better.

Available for rental or purchase on demand on VHX, PBS premiere 06/30/2025

The Opiate of the Massively Multiplayer

Eat the Night

(dir. Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel, 2024)

There has only been one game titled Second Life, but the term itself can be applied to gaming as a whole. Any hobby can fill one's time, and novels and TV series can be significant commitments, but intrinsic to games is agency, the open-endedness and flexibility that can allow a game to subsume a player's entire life if they let it. A game asks for input in ways that other media do not, with an experience co-authored by designer and audience alike. Its outputs and rewards are most rewarding within its secondary world, perhaps too much so; your avatar may have spent hours adventuring, but what about you? What were others doing in the meantime?

This duality is at the center of Eat the Night, a combination of gay crime story and online gaming chronicle. Small-time drug dealer Pablo (Théo Cholbi) and his teenage sister Apolline (Lila Gueneau) are avid players of MMORPG Darknoon, until a message from the developers announces the game will be shutting down in one month's time. Pablo meets Night (Erwan Kepoa Falé), a retail stocker who he recruits as both business and romantic partner. This leaves Apo with nothing to do within Darknoon and without, until Pablo's conflict with a rival drug operation escalates and starts having very real consequences. It is an intriguing combination, though perhaps inevitably the two aspects don't fully cohere.

The relationship between Pablo and Night is understated and sweet, and set in a grubby milieu whose queer population doesn't get enough attention relative to its more affluent brethren. It's got a subversive charge, Be Gay, Do Crime and all that. Yet their storyline mostly exists apart from Pablo's relationship with Apo, a codependent shut-in who is left adrift without her brother. This makes sense in the real world, given the hermetically sealed worlds of games. But while the fake world and UI of Darknoon as a game-within-a-film has been convincingly built from scratch (more than the live-action footage, whose underlighting betrays its low budget), the nature of the game itself remains unclear.

From what we can see, the game is more of a violent hack-and-slash affair, looking like a kinkier Final Fantasy XIV, with decapitations. Its goals are vaguely defined by Apo herself as essentially 'level up your avatar and kill things,' which is maybe an intentionally reductive parody—the over-the-top violence has shades of Elle—but such garishness shortchanges the appeal of these things to someone like Apo. It's not that the lore of a fake video game is important in itself, but knowing what the game is about could have allowed more insight into Apo and given her something to do, the craved illusion of agency, before she and Darknoon become more woven into the crime plot.

It is awfully effective when that finally does happen, thanks to a nifty shift in machinematography. The majority of Apo's episodes of wandering through the game are shown in-engine, sometimes as straightforward behind-the-character gameplay, other times cheating the camera positioning but still 'from the outside in,' as a player views their blocky character. The subtler player interactions, however, are done in pre-rendered CG animation with detailed facial expressions and gestures, allowing the scenes to play how they feel rather than merely how they look. It's satisfying, even lending some support to the absence of in-game context, as a simulation of the bewilderment felt by a spectator seeing an unfamiliar game. It makes the apocalyptic conclusion especially effective, enough that I suspect the movie's plot was reverse-engineered to arrive at it.

The movie still doesn't make a strong case for the connection between gamer culture and gang warfare, and now that I've typed that out it seems even more obvious. Yet I am partial to Eat the Night's intersection of new and old media all the same, and the possibilities it suggests, that as our real and fictional lives collapse and fall away, we may all still come together again.

Available to rent or buy on Vimeo

The Canary in the Craft Mine

A Minecraft Movie

(dir. Jared Hess, 2025)

Has there ever been a more critic-proof movie than A Minecraft one? The built-in audience is dwarfed only by that of The Super Mario Bros. Movie a couple years ago, and will only be potentially bested by the inevitable Fortnite and Roblox Movies. That audience, of the coveted 30-and-under bracket plus some of their suffering parents, put it on the path to being one of the biggest movies of the year, with an $922 million international haul so far, with $500 million of that made in its first week.

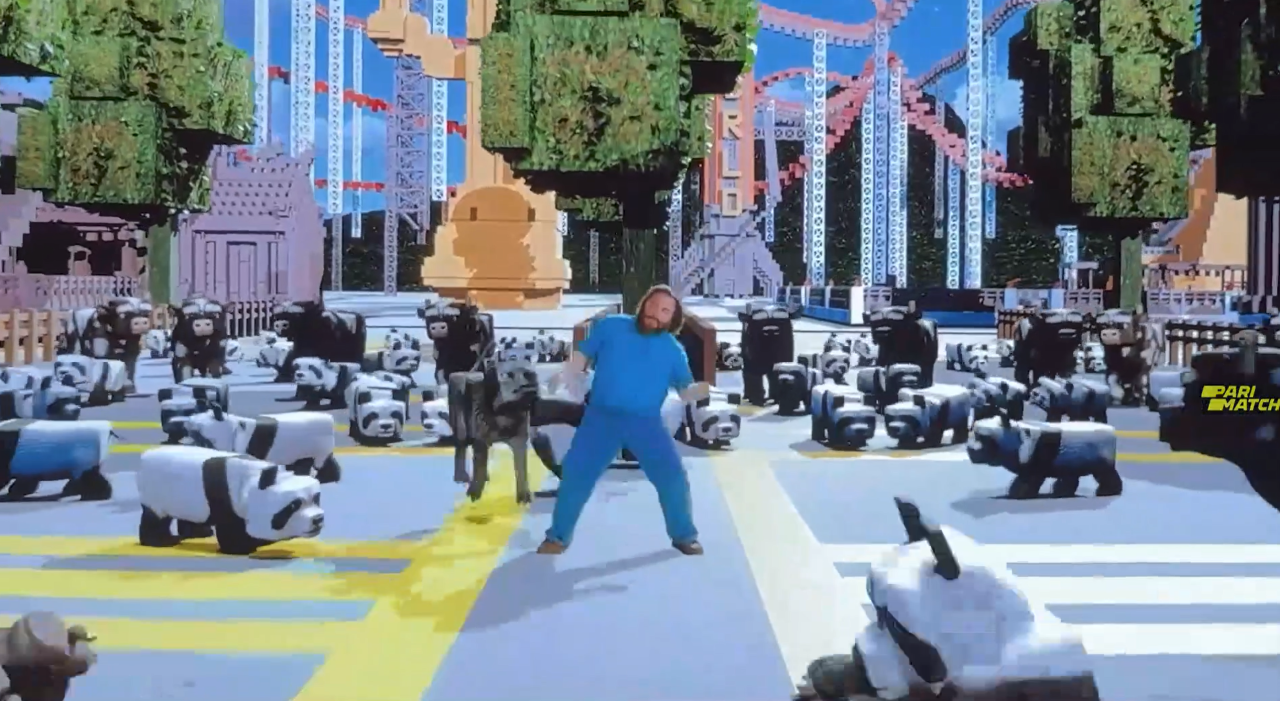

The sheer numbers overwhelm any appeals to judgment. It is beside the point to grouse about the hideous 'realistic' design of the game's distinctive blocky voxel map and models. It doesn't matter that most of the dialogue is high-pitched yelling, and that the story of a group of misfits transported into a magic world is a jerry-rigged fetch quest with a layer of insincere kid movie lessons lacquered over. It matters least that the decision to treat the game's ramshackle framework for building stuff as a coherent world results in exposition and worldbuilding that amount to a gameplay tutorial. That is why the audience is there.

What I was there for was the audience itself and the behavior which made A Minecraft Movie into not just a hit but a zeitgeist earthquake. As all of their favorite memes were incantated, particularly an arcane line about a "chicken jockey," kids and teenagers in America and the U.K. were going nuts, trashing theaters from Utah to upstate New York. My matinee audience was disappointingly (blessedly) well-behaved for the most part, but they too partook of the chicken jockey rite, a unified chant that was all the more disorienting for being so out of place. I actually don't want to dwell on this; complaining about teenagers is the oldest, laziest form of criticism, followed closely by contrarianism. Taste is less about eternal truths about art than post hoc rationalization and social signaling, class politics by another name. That I dislike an object of popular adoration says much more about me than it does the populace.

This is, fittingly, a similar position I found myself in when it came to director Jared Hess' debut film. A Sundance smash filmed on a shoestring budget in Hess' hometown of Preston, Idaho, Napoleon Dynamite came out in 2004, the year I graduated high school in McCall, six hours north-northwest of Preston, and the hype was inescapable. When I finally saw it a couple years later, I was cool on its quirky, deadpan take on rural self-amusement.[1]

I still don't care for this style, but the Hess-isms present in A Minecraft Movie are precious droplets of personality amid the corporate desolation. There is the small-town Idaho setting where the real world material is set.[2] There is a featured tater tots dish, and nunchuks of a sort, along with an incomprehension of Spanish that is too guileless to be considered mean. An awkward dance at a talent show is a pivotal plot point. Jack Black's casting likely owes as much to Hess, who directed him in his sophomore effort, 2005's Nacho Libre, as it does The Super Mario Bros. Movie.[3] I chuckled at a line about a "Mogul Zoo," a pun that will only register with people who have spent time in Salt Lake City. The non-sequitor humor in general is, for lack of a better term, Mormon-coded in its aversion to offense, and the tic of doing a random thing and then dwelling on and pointing at the random thing is Napoleon Dynamite's deadpan pauses with the volume turned up. That's about it for personal stamp in the Minecraft sections, though, which are otherwise ugly and loud and overproduced.

Beyond unanswerable questions of taste, the principle objection to all this is how it mouths platitudes about creativity, while leaving as little to the imagination as possible.[4] The visual charm of the Minecraft game is in its suggestive voxel graphics, where a world and everything in it are effectively made of building blocks. Attempting to render all of this in a photorealistic style, where the 'Villagers' have the same super-deformed proportions but also individually rendered pores and skin creases and strands of hair, is grotesque.[5] Two decades ago the Lord of the Rings movies judiciously mixed computer animation and animatronics to convince its audience that orcs and trolls were physical presences, and today the Avatar movies have gone all-in on their effects to the same end. No effort is made in A Minecraft Movie to convince that the actors, and by extension their characters, are actually interacting with anything but millions of dollars in effects. The CG sheen is not as pervasively ugly as e.g. Snow White, but it nevertheless registers as slick, slimy digital artifice.

Yet unlike other modern blockbusters with a lazy-yet-expensive dependence on visual effects, we can actually see how that deadens the souls of the movie and the people watching it. Shortly before release a workprint leaked online with TBD credits and visual effects in various states of incompleteness, and it is a positive revelation.

The over-designed realism is stripped away, in effect making the designs more consistent; the CG characters look like untextured assets from a 90s CG TV show, and the environments actually look like building blocks rather than unnaturally (yet inconsistently scaled) geometric life forms. Little has been done to blend the actors with the effects, with harnesses and cables still visible on airborne characters. The stripped-down look also reveals how much of the movie actually was filmed practically, with sets like the Overworld fields and a trap-filled cave having an 80s fantasy movie tactility that is lost under layers of post-production. Where the unmodulated screechy performances have a kind of horrible unity with the tacky CGI in the official release, in the bootleg's Nick Arcade aesthetic they attain a kind of B-movie theater kid energy, determined to make the audience believe what they're seeing out of sheer will. The movie remains bad, but it has the element of surrealist surprise missing in its over-written 'lol random!' humor.

Video games, including Minecraft itself, are the most vivid secondary worlds humans have devised. Yet tThat same vividness, as well as the intellectual properties being jealously guarded by their corporate owners, reverses the process like a backed-up drain. The secondary, fictional world begets a tertiary creation, but back into the real world, to which it bears no resemblance. It exists only in reference to the game, not an adaptation as much as an adjunct. The rise of Minecraft from an off-beat solo-developed indie game into a generation-defining media giant, the ingenious creations made within its framework, these are intrinsically compelling; there's a reason millions of people play in this sandbox. The only reason anyone would want to engage with A Minecraft Movie is a pre-existing connection to the source material. Seen in that light, the movie's attendant bachannalian memery reads as the youth misguidedly trying to brute-force some form of frictive novel engagement with a product that was engineered to be as passively consumed as a Happy Meal. People will find ways to assert control when they are powerless; somebody should make a movie about that.

The workprint copy is floating around the internet. You'll find it easily enough.

Letterkenny is a far sharper take on the subject, in part because its deadpan dialogue is delivered at a hundred miles an hour, where Napoleon Dynamite lingers constantly on awkward pauses.

↩︎Though if criticism were actually relevant here I would make a larger point about how the unmodulated wacky tone of this 'real' world is indistinguishable from the goings-on of the minecraft Overworld.

↩︎After Nacho Libre and Gentleman Broncos Jared Hess seemingly fell out of popular culture, but he's been working all the while, with an impressive roster of name talent including Jennifer Coolidge (here in an amusing bit part as a recently divorced school principal), Sam Rockwell, Zach Galifianakis, Amy Ryan, and Owen Wilson.

↩︎The best-case scenario for A Minecraft Movie was done over a decade ago with The Lego Movie, another adaptation of a building-blocks toy but one that took the care to cleanly separate its real and fantasy worlds to make a statement about them. If it is no more sincere as a feature-length commercial, it is at least more convincing.

↩︎The only reasons I can come up with for why this was a deal-breaker for audiences with the dwarfs of Snow White or the initial reveal of Sonic the Hedgehog but not here, are either that Minecraft has a larger fanbase than those original properties, or that that fanbase is alarmingly less discerning.

↩︎

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion