New Year, New Newsletter

Greetings! With the first year of Cinema Purgatorio in the rearview mirror I wanted to step up the presentation here, with more photos, with credits and alt text. Since I started this newsletter a lot of other shorter reviews have lived on my Letterboxd. I've shared these on various social media, but rather than continuing the dying web trend of “five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of the other four,” I'm going to try to include a mix of smaller pieces and odds and ends and give the newsletter more variety. I'll still be on the Boxd, and I even branched out and started a fledgling TikTok account for snap reviews. Do tell me what you think, about the format, the length, frequency of posts. Ghost's metrics don't tell me a lot about what "works," and I don't want to become too grossly indulgent.

In today's missive, I cover the passing of David Lynch, Audra McDonald and Carrie Underwood, The Substance, and the video game documentary Grand Theft Hamlet and its implications for theatre and gaming.

The Peak

I came to David Lynch's work relatively late. I had seen Dune and Blue Velvet years ago, watched the Twin Peaks pilot, and had seen and been baffled by Mulholland Dr. I didn't do a real deep dive until the summer of 2019. I was in a low place then, and Lynch's work was a revelation. There's his weird style, of course, but what grabbed me was how much he got the Pacific Northwest, how the original run of Twin Peaks brought back sense memories of growing up in a mountain resort town in Idaho in the early 90s. I was also taken by Lynch's deep, humanistic empathy. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a disturbing, deeply sad portrait of troubled high schooler Laura Palmer in the last week of her life, but its final moments are full of redemptive grace and one of the most beautiful things he ever made.

This warm-heartedness comes through especially in The Straight Story, which I wrote about last year and re-watched with my mother the day the news broke. (She started looking up Lynch on YouTube afterward and a few nights later she pulled up his surreal nightmare sitcom pastiche Rabbits for us to watch, which shows how cool my mom is.) His career had its ups and downs—I re-watched Dune and was still confused even after seeing the Dennis Villenueva adaptations—but he and his career are a testament to following your artistic instincts with no regard for commercial considerations. There's a Twin Peaks photo slideshow on YouTube set to Julee Cruise's song "The Nightengale" that I've always loved for its wistful mood, and it hits even harder now. There will never be another like David Lynch, but there are no others like you, or me, or anyone else. We all have something to offer, it's just a matter of taking the leap.

Grand Dame Guignol

The Substance

(dir. Coralie Fargeat, 2024)

As luck would have it I saw The Substance the night before it received five Oscar nods, including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay, but after Demi Moore's Best Actress win at the Golden Globes, and a Best Screenplay award from the Cannes Film Festival, whose laurel graced the opening of the movie. I am mystified at this hype. I'll grant Moore her plaudits, she is committed to whatever crazed direction the screenplay sends her. That script, however, is a giant mess of stray parts and conflicting impulses not unlike the one that features in the movie's bananas climax. It is silly and dumb, collapsing time, distance, and basic biology. Stuff like cells dividing and popping out of themselves more or less instantaneously, is just movie logic, same with how TV shows here are closed and rebooted within a matter of days. It's also not so much an issue because the directorial style is so cranked up, full of gross-out close-ups, with sound design magnifying every possible slurp and gurgle, and all of the men portrayed as grinning, leering gargoyles. As an expression of rage, puking up the media's most revolting misogyny back in its face, it is bracing filmmaking.

Moore's aging TV star Elizabeth, however, is just a total nothing of a character. She doesn't actually get anything out of growing a younger version of herself, Sue (Margaret Qualley), who switches places with her every seven days. When Sue breaks protocol and begins feeding on Elizabeth's vitality, she has no response but self-pity. Yet there's no sense that Elizabeth is a victim, because she has no thwarted dreams beyond her beauty, and doesn't do anything to assert her agency until very late in the film. If the movie ended with the consequences of when she does so, I would have left slightly annoyed for taking so long to go nowhere. But then it keeps going and going, and topping itself, for the sake of topping itself. It gets so dumb, but it is so committed to its garishness, with gleefully disgusting special effects and ending on the most perfectly stupid shot, that it literally took my breath away with laughter.

The Substance is a collection of disreputable setpieces strung together by agreeably feminist anger that makes collateral damage of its protagonist. It's not smart, but it is unhinged, which is almost as good.

Some People

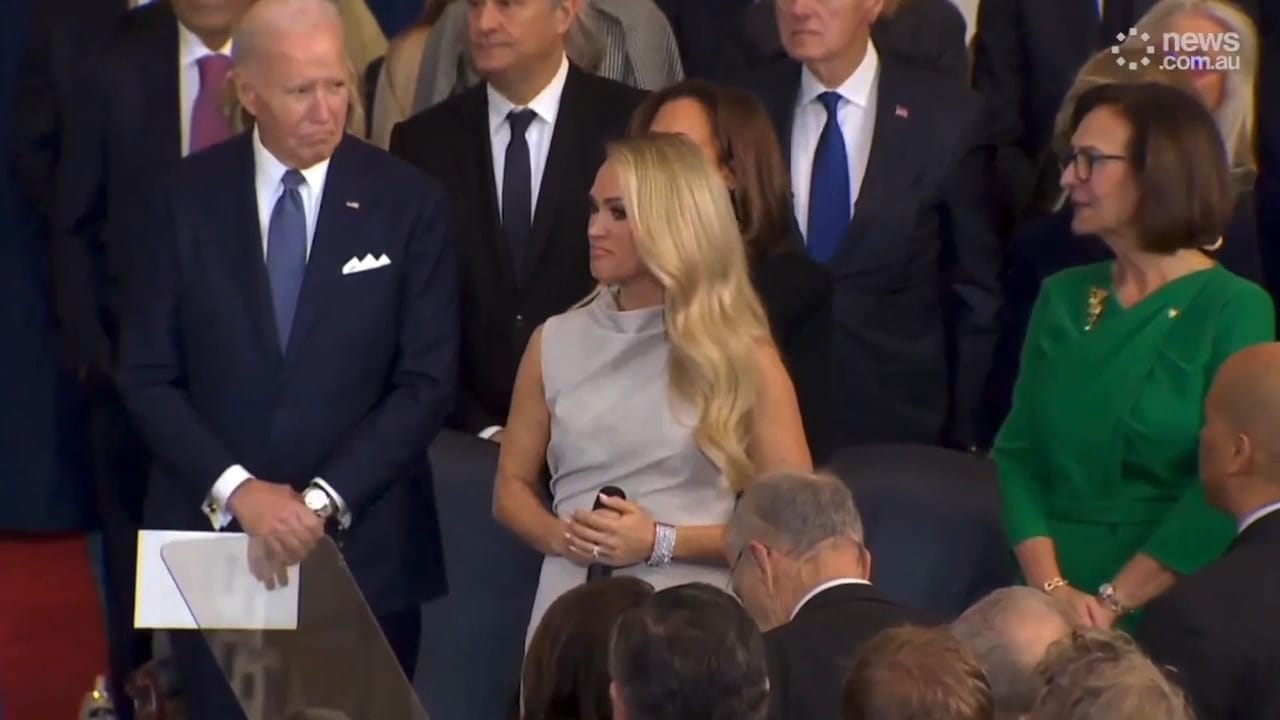

Carrie underwood and Audra McDonald, a study in contrasts. Photo credits: News.com.au, Julieta Cervantes

Last weekend I was in New York and saw the revival of Gypsy starring Audra McDonald as Rose. The show is already one of my favorite musicals, with not a weak link in its songbook and a story that even today is surprisingly dark. McDonald kills it, bringing her operatic voice down to earth with a ferocious hunger very fitting. Before now my standout memory of McDonald was as the Mother Abbess in the NBC live production of The Sound of Music starring Carrie Underwood, who she blew off the stage with her rendition of "Climb Every Mountain."

The format of a live performance with no audience was incredibly weird while it lasted, and no more so than this production. It was filmed at 60 frames per second, the standard for live events like news reports and sports as it feels more 'real.' For the most part it felt like a filmed rehearsal, with the typically expressive blocking of theatre but also long awkward pauses where the audience applause should be. But in the sequence where the Von Trapp family has to perform for the Nazis at the Kaltzburg Festival, the show took a detour into the uncanny. Because the family in the story is on a stage and performing, presenting themselves to a visible audience, the theatrical artifice faded and in fleeting moments it actually looked like a broadcast of a Nazi rally with a photogenic family performing. It was a strange accidental intersection of form and content.

Incidentally the day after I saw McDonald in Gypsy, Carrie Underwood performed at the presidential inauguration, after two minutes of awkward silence due to a microphone glitch. Life takes people in different directions.

ACT I. Slings and Arrow Keys

Grand Theft Hamlet

(dir. Pinny Grylls, Sam Crane; 2025)

I can take any empty space and call it a bare sage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.

So began The Empty Space, Peter Brook's slim but dense 1968 volume that anatomized the theater of his time—deadly, rough, holy, immediate—and went on to inspire a generations of thespians. Among its legacy is the entire mini-medium of site-specific theater, staging the action of a play not on an artificial set constructed on a stage set apart from the audience, but in functional spaces—record stores, historic sites—that dissolve the barriers between acting and the actual, actors and their audience. Actor Mark Osterveen, in the Q&A session that followed a January 18 evening screening of Grand Theft Hamlet at New York's IFC Center, cited Brooks' dictum and site-specific theatre as a framework for thinking about the staging of William Shakespeare's Danish tragedy within the digital playground of Grand Theft Auto V that the film follows. Grand Theft Hamlet pitches itself as the first staging of Shakespeare's play within a virtual world, and while this is inaccurate—the nonprofit A Stage Reborn has been staging plays, including A Midsummer Night's Dream, in Final Fantasy XIV for over half a decade now—it's certainly one of the most quixotically entertaining cases for digital spaces as a performance medium.

The doc begins in 2021, when London has entered its third coronavirus lockdown. Stage actors Oosterveen and Sam Crane find themselves out of work like the rest of their peers, and so they take to the online multiplayer edition of Grand Theft Auto V's Los Santos to stave off boredom. Stumbling on the Vinewood Amphitheater they wonder if its full-size proscenium performance space might be used to stage actual plays. An early attempt at Hamlet's Act 1 Scene 1 between two guards wary of intruders is performed in parallel with a firefight with their audience and then the police, dialogue like "Not a mouse stirring" interspersed with pleas not to kill the actors. This is enough to convince them to keep going and bring in Sam's documentary filmmaker wife Pinny Grylls to record their process. The resulting film takes place entirely within the game.

Machinema can only look as good as the game its made with, and Grand Theft Hamlet is lucky in this respect. Grand Theft Auto V is over a decade old, released two console generations ago on the Playstation 3, but developer Rockstar Games took great care in recreating the milieu of Southern California, and the game's hazy orange sunsets, cresting ocean waves, and raindrop-rippled puddles remain hypnotically gorgeous. The human avatars are less so, stylized but also with a focus on facial detail that, befitting the game's nihilistic fratire, makes even the hot character models look vaguely gross. Their mouths move at regular intervals, creating moments where conversations will briefly sync up before dropping off-time again. It's appropriate for a piece that sits at the crossroads between the real and fictional worlds.

As far as the actual play performance goes, the digital actors' expressiveness is all conveyed through motion-captured emotes and the choreography of player movement. The emotes make for some effective smaller moments, particularly one actor's audition with a monologue from Julius Caesar punctuated with judicious kitchen knife stabs and an 'off with his head' gesture, but for practical reasons Sam and Mark settled on a streamlined approach to the blocking: characters who were not speaking would stand in place, while those who were would move and repeat an emote for emphasis. (Q&A moderator Jeremy O. Harris compared this to the Brechtian 'Gestus,' the gesture of the gist, that isn't a naturalistic action but instead communicates an essential truth of a character's relation to another.) The third-person camera is of limited use—for all that modern video games vainly attempt to be "cinematic," they must always sacrifice presentation for readability when the action revolves around twitch reflex target shooting—but Pinny's use of the first person camera allows for more deliberate framing and for Sam and Mark to treat it as a proper camera, an all-seeing eye that can be ignored or addressed.

That this is all in-game, in-engine, is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the consistency in presentation is welcome. Los Santos may have been eclipsed in size by later game worlds, but its variety in settings and activities has helped keep it alive for twelve years. That flexibility is what made the Hamlet project possible in the first place, and the logistics involved are worth the time the documentary spends on them. The eventual performance was not staged in the Vinewood Amphitheater as originally proposed; instead Sam and Mark approached their production like a real-world site-specific piece. Each scene unfolds in a different locale, a bar or a rooftop deck, with the amphitheater used as the site of Hamlet's play-within-a-play. (Tom Stoppard's film adaptation of his play Rosencrantz and Gildenstern are Dead added to the metatextual density by inserting a recursive puppet show, but here in a documentary that takes place in a game it works in the opposite direction, a play-within-a-play-within-a-game-within-a-film. Hamlet itself is at most the secondary work, set within the confines of the primary work of GTA.) The spectators are ferried scene-to-scene by boat, van, jet, and memorably, a hot air balloon that serves as the Ghost's entrance, rising into view at the top of the city, and then crashes and kills all the actors and audience. As the game is a violent crime simulator, death is an even greater fact of life than it is in real urban environments but also a much more trivial one. It is a factor to be managed and mitigated, like terrible acoustics or a hostile crowd. The perverse tension between what GTA was designed for and how it is used here is always very funny, and as a work of make-do proleterian art and entertainment that meets the audience where they are, what Peter Brook called "the Rough Theater," the Grand Theft Hamlet production is a success.

INTERMISSION

Originally surfacing after the death of David Bowie in 2016, this made the rounds on Bluesky after David Lynch passed away last week, and I am feeling it:

ACT II. The Undiscovered Country

But is GTH productive? The project starts running into trouble in 2022, when lockdowns lift and the world begins to reopen. Rehearsing becomes more difficult as the cast start having to attend to their real life obligations outside the home. Sam and Mark's first pick to play Hamlet, Dipo Ola, has to step back to a smaller supporting role when he gets cast in a paid role. Sam ends up taking it on, and the project begins to take up so much of his time he misses Pinny's birthday. These are not unique difficulties, and are in fact endemic to actors' lives. "I can't, I have rehearsal" is a refrain that begins in college drama departments, and Los Angeles indie theater exists in the shadows cast by the film iand TV industries. But the self-contained universes of games and their commercial incentives often cultivate an insularity that seals them off from the rest of the culture. The rehearsal for GTH was all done in-game, but the full story of its production involves goings-on beyond. The doc's narrative and its visual and editing scheme could have gotten a shake-up by opening up to include the real world.

The limits on the film are indicative of the in-game form. As logistically impressive as the Hamlet performance is, the crew is fighting against the limits of GTAV at every turn, and they can only do so much within them. Assessing the dramaturgy of the piece–among the inevitable cuts for a two hour runtime is Norway's prince Fortinbras—is secondary to marveling at the fact that it was pulled off within the game at all. It's the kind of second-order creativity that defines fan work, that always exists in reference to, if not within, an IP ecosystem. Crane's YouTube profile describes his work as "appropriating digital spaces for live performance," and as heartening as it is to see GTA's nihilistic attitude subverted for more positive means, that second-handedness still ultimately benefits Rockstar Games.

I wanted to ask the panel at IFC, given their experience performing in GTAV, whether they would want to do so in another established title, or if they wish there was a dedicated platform for digiplays or whatever we're calling this. Surely a bespoke platform would allow for more flexbility and freedom, but it would lack that man-bites-dog appeal. In effect, performing Hamlet is a sort of challenge run, like speed-running or not violating any traffic laws.

There is untapped potential in the intersection of theatre and video games. Just as a stage can be anywhere and anywhere can be a stage, a code base can be made to show anything, and anything in turn can be explored. The mind thrills to imagine the possibilities of a framework that gives performer-players the tools to express actions beyond both the stock and standard run-and-gun of the AAA games industry, and the physical limits of live performance. What kinds of stories might present themselves, what impossible abstractions might be realized? (This is, of course, the perennial hope of video games as a whole.) Only when the performers need no longer follow someone else's script will they be able to write their future. For now, efforts like Grand Theft Hamlet exist as a kind of digital folk art, salvaging scrap from the garbage heap of corporatized popular culture to make something personal and idiosyncratic. The play's the thing.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion