On Just Existing

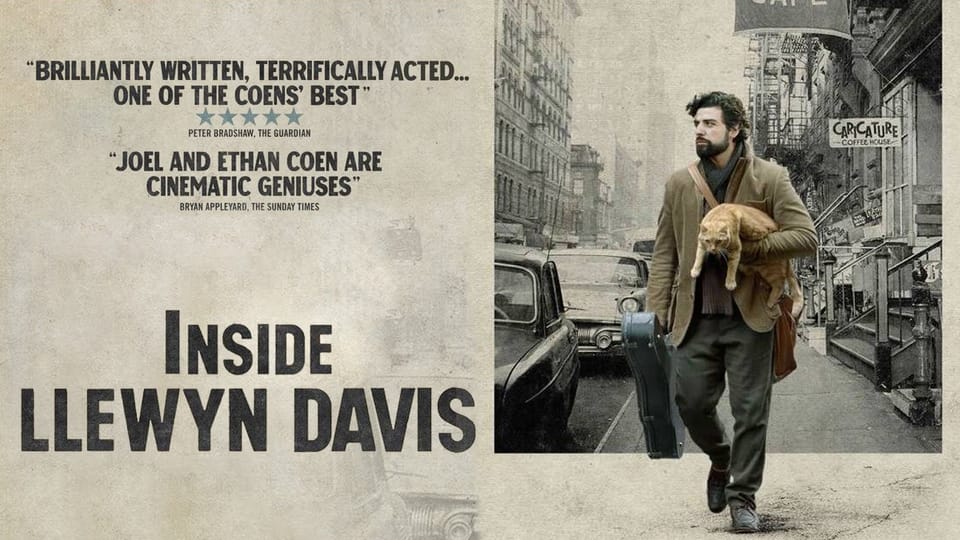

I couldn't think of a better topic for the launch of Cinema Purgatorio than a deep dive into Inside Llewyn Davis on the 10th anniversay of its wide release, give or take a day. Not every missive will be this long, but it's my favorite film, and as a look into the abyss of creative purgatory it is surprisingly relevant to how this newsletter came to be.

I. Five Hundred Miles Away From Home

In a film full of cutting lines, the sharpest exchange in Inside Llewyn Davis comes when the titular folk singer, played by a hollow-eyed Oscar Isaac in his breakout role, pays a visit to his sister Joy in Long Island. Llewyn won’t admit to her outright that “the music” is not going so well, but she can infer as much, and so she asks him if he still has his seaman’s papers, elliptically suggesting that the service could be an option if the music isn’t working out. Llewyn is incredulous.

“What? Quit? Merchant Marine again, just… exist?”

Joy is almost as amused as she is offended. “Exist? Is that what we do outside of showbusiness?”

She continues:

“It’s not so bad, existing.”

“Like dad.”

“Llewyn.”

“What?”

“You say that about your own father?”

“What?”

“That he exists?”

“I didn’t say it, you said it—”

“That he exists? Like that?”

“Yeah yeah, I’m sorry.”

It’s a darkly funny moment, arguing about whether their father exists as if that were an insult. But for Llewyn it may as well be. He is living the Bohemian dream, making a living playing folk music in Greenwich Village. Other people, normal people, make do with the spiritual death of everyday living, but Llewyn is serving a higher cause, of music, of capital-A Art. He may be in a bad way, sleeping on the sofas of people he hasn’t yet completely alienated, and has been ever since his music partner Mike threw himself off the George Washington Bridge to physical death the year before—but no matter. At this point Llewyn still reflexively dismisses any alternative to the path he’s chosen. He continues to keep the faith.

That’s what a creative career is for most who pursue it: faith—in oneself, in one’s work. One of the first and most important things you learn as an artist, in any medium, is that you become that simply by doing it and identifying it as such. If you write songs, you are a songwriter, it you write plays you are a playwright, you do not need permission or a bestselling hit to call yourself one. You will find more satisfaction waiting for Godot than you will waiting for validation in the form of awards and bags of money.

Yet self-definition as an artist does not preclude one from being compensated for it. Depending on how much money is going around, workers in some fields are fortunate enough to have enough demand and a low enough cost of living to support themselves. So it is with Llewyn and his cohort. Except for exceedingly polite visiting Army officer Troy Nelson, who’s been playing and recording between his tours of duty, everyone in this Greenwich Village milieu are making a living solely as musicians: playing sets at the Gaslight Café, performing as session musicians for one-off recordings, and pressing an album in the hopes that it catches on and leads to bigger and better things.

Llewyn at least has his meager income to show for his efforts, concrete proof of his vocation; these days one often has to work a day job, or two, while chasing that artistic dream, especially in New York. No less an authority than David Byrne said, in an op-ed published two months before Inside Llewyn Davis’ December 6, 2013 premiere, that the city had become prohibitively expensive for artists to do more than, well, exist.

[M]ost of Manhattan and many parts of Brooklyn are virtual walled communities, pleasure domes for the rich (which, full disclosure, includes me), and aside from those of us who managed years ago to find our niche and some means of income, there is no room for fresh creative types. Middle-class people can barely afford to live here anymore, so forget about emerging artists, musicians, actors, dancers, writers, journalists and small business people. Bit by bit, the resources that keep the city vibrant are being eliminated.

I was one of those emerging artists. I had arrived in New York six months before, with the goal of making it as a playwright, whatever that meant. Financial remuneration was never in the cards—playwriting is not one of those aforementioned fortunate fields, even the playwrights with the most cultural capital like Tony Kushner or David Mamet make their normal capital from teaching or Hollywood—but I had hoped to get produced, make a name for myself, get my work in front of a big audience. Not for fame and glory (or at least not just for those), but for the pleasure of having people respond to something I had written.

When I saw Inside Llewyn Davis in theaters I winced on hearing that word “exist,” winced in recognition. I had left my hometown in Idaho a few years before; a year after graduating from college I had started going stir-crazy, directing a couple shows at the local community theater to keep myself from going completely insane. By the time I arrived in New York I had internalized the attitude that just existing was, if not beneath me, then at least insufficient. During this time I would literally get myself hyped with the opening number of Gypsy, Rose’s aspirational anthem, “Some People”:

Some people can be content

Playing bingo and paying rent.

That's peachy for some people,

For some hum-drum people to be,

But some people ain't me!

You pretty much have to believe this on some level in order to pursue the arts. It is so much work for so little compensation when you could be building a career in a field that actually pays its laborers a living wage—you have to believe that somehow it is better than that; otherwise what the hell are you even doing?

Llewyn was an asshole, but he was an understandable asshole, relatable in ways most would not care to admit, and I appreciated the film’s abrasive honesty. In subsequent years its abrasions would become only more relatable, cut even deeper, in ways I would wish even less to admit.

II. The Last Thing On My Mind

The next time Llewyn sees Joy, some 75 minutes and a week later, he will have come around on returning to the Merchant Marine. At that point he has gone through a series of humiliations that have ground his determination to dust. Losing, then finding, his Upper West Side academic hosts the Gorfeins’ cat; signing away royalties for session work on a novelty song (the very funny “Please Mr. Kennedy”) in order to get the cash he needs immediately to pay for his ex-girlfriend Jean’s abortion; learning that the solo album he recorded after Mike’s death has failed to sell; exploding at the Gorfeins and then learning the cat he brought back has no scrotum; discovering that another ex-girlfriend whose abortion he paid for kept the child without ever telling him; enduring the degrading insults of a heroin addict Jazz musician in order to get to Chicago; and finally, failing an audition for a respected club owner, who advises him to rejoin his dead partner. He returns to Jean, who he can’t even remember is having the abortion on Saturday, and admits defeat. “It’s not going anywhere, and I’m tired…. I’m so fucking tired. I thought I needed a night’s sleep, but it’s more than that.”

It's not just his present failures that weigh him down, but his past success. Immediately after the earlier argument with Joy about just existing, she brings out a box of his belongings salvaged from their parents’ house, including a recording of “Shoals of Herring” Llewyn made for their parents when he was eight. He tells her to trash it, with the reasoning that “in the entertainment business you don’t let your practice shit out, it ruins the mystique.” On first viewing this seems like the character’s usual insufferable self-aggrandizement. On a rewatch, knowing where this is all going, it’s clearly a deflection, a pivot away from Llewyn’s discomfort with a reminder of a time when music provided a simpler satisfaction, one might say joy. After deciding he’s had enough with music and will return to the Merchant Marine but before he learns that that will be impossible, Llewyn visits his father in a nursing home and does try to recapture the good old days by playing the song for him—only for the old man to soil himself. There truly is no going back.

Everywhere Llewyn goes he is reminded of better, more optimistic times. The Gorfeins have a copy of the album he cut with Mike, and his label is getting rid of all the unsold copies to make room in storage. Llewyn’s angry blow-up at the Gorfeins is triggered when he is playing for their other guests and Mrs. Gorfein starts singing Mike’s harmony. Jean accuses Llewyn of not caring about the future, but as much as he is stumbling through the present, he is also mired in regret and loss that prevents him from moving forward.

This, too, would end up cutting uncomfortably close. By the end of 2015 I had been in New York for over two years, away from home for five, and writing plays for over ten, and in that time had made little progress. I had done some workshopping and a couple readings of my scripts, and had even been a finalist in that year's Eugene O'Neill National Playwrights Conference—but none of this had translated into a single production. Unlike a novel or a poem (or a self-published internet newsletter), a play is not finished when the writing is done; it needs actors and an audience. A play without a production is a blueprint without a building, and all I had to point to for my efforts were some empty lots. After more than a decade of writing scripts, the only actual production I had was some self-produced shorts I had done at the community theater back home before I, nominally, decided to seriously pursue a career. Playwrights can and do spend much longer "emerging," it is a brutal field, but this creative impotence threw into doubt the whole idea of self-identification; could I really call myself a playwright if my output was all 'write' and no 'play?'

The reasons for my failure to launch are too dull to recount, and they hardly mattered except they were sufficient fuel for self-recrimination. I spent 2015 and 2016 morbidly depressed, haunted by my ongoing failure to live up to my potential. In a particularly bleak Coens-esque twist, at one point I attempted to get a therapist to help with my career malaise through an organization that provides services to professional artists—but I didn’t have the professional status to qualify. It was here Inside Llewyn Davis began to reveal its callused heart to me.

III. The Death of Queen Jane

The stories of artists and musicians we typically hear, usually in Hollywood biopics, are of the stars. They are famous. They have, by definition, made it. As such there’s a survivor bias at work, in which the success stories become the only stories told, implying if not stating outright that with enough work you too can triumph over adversity and get your big break. The opposite is true simply as a statistical fact: the corollary of most artists making little to no money is that if they don’t graduate to making more than that, they either toil in perpetual obscurity or wash out of their field altogether. David Byrne gets at this in another part of that op-ed:

As one gets a little older, those hardships aren't so romantic – they're just hard. The trade-off begins to look like a real pain in the ass if one has been here for years and years and is barely eking out a living. The idea of making an ongoing creative life – whether as a writer, an artist, a filmmaker or a musician – is difficult unless one gets a foothold on the ladder, as I was lucky enough to do. I say "lucky" because I have no illusions that talent is enough; there are plenty of talented folks out there who never get the break they deserve.

For so many, the passion that sustained them when they were younger has been completely spent on an unsustainable way of life. What about them? Where’s their biopic?

Llewyn Davis is an avatar of that quiet failure, albeit one who says the quiet part loud. His bridges burn much brighter than in real life—many of us have robbed Peter to pay Paul, but how many of us have borrowed money from Paul to pay for his wife Mary’s abortion?—but Llewyn’s resentments are all only exaggerations of the insecurities that gnaw at any creative striver. There is his refusal to even consider civilian life, of course, but also the way his creeping despair poisons his interactions and becomes self-fulfilling. His palpable professional jealousy as a crowd begins to sing along with Jean and her husband Jim is relatable to anyone who has seen their friends—and foes—get ahead and asked themselves, “Why not me?” His wary, resentful negotiation over whether to accept a meal or a winter coat is born of the real tension of never having enough money and having to receive help that is as needed as it is unwanted.

And then there’s the way Llewyn rationalizes his hair-shirt living. He sees his precarity, even if it means living at the generosity of others, as real and honest. The morning after sleeping on Jean's floor she brings him his things at Caffe Reggio and ends up calling him out on being a self-interested disaster. He responds that looking to move to the suburbs and have kids like she and Jim do is “a little careerist… a little square… a little sad.” There’s comfort in purity, in clinging to moral victories while losing on every other front. Often this stubbornness is justified, and sometimes it even pays off. But most of the time it doesn’t.

The most painfully recognizable aspect of Llewyn is his weary recognition that “it’s not going anywhere.” People who structure their lives around their art, even if they aren’t making money off of it, will have their identity wrapped up in it. Their work becomes their baby, especially if they don’t have a spouse and an actual baby. This is not healthy, but it is practically inevitable. Without a hierarchical career ladder to climb, the artist has to assemble the ladder themselves, and any downtime not spent doing so just kicks the big break further down the line, beyond the horizon. To walk away from that is like walking away from yourself; it’s inconceivable.

I couldn’t walk away from writing, even if I wanted to. My entire time in New York I worked as a server in Times Square. The job came with plenty of stresses of its own and only really made sense in the context of a creative career that needed the flexibility in scheduling. I wanted something else, but on top of the job paying stupidly well and therefore making it harder to find something else, I also had no work experience that would make me hirable in a normal 9-5. And so I doubled down: I enrolled, with considerable preparation and effort, in an MFA program in playwriting and screenwriting, with the vague idea that I would emerge with the knowledge to make a living with my writing.

And so, like Llewyn, I went to Chicago.

IV. The Roving Gambler

After going to the Windy City and back and still managing to go nowhere, Llewyn resolves that he will return to the Merchant Marine, but the process of doing so is a cascading series of one step forward, two steps back turnarounds and reversals. He goes to the union hall to re-enlist, only to learn he is in arrears: he owes the union $148. With the remainder of the $200 in cash that he made on “Please Mr. Kennedy,” he settles his debt. He drops by Joy’s house to get his seaman’s license—only to learn that it was in the box of his personal effects that she dutifully put to the curb. So he returns to the union hall to get a replacement, only to find that costs $85 he doesn't have. Hoping to salvage his money as well as his dignity, he attempts to get a refund and is instead rebuffed; you don’t get refunds on union dues, least of all on money owed. Unable to make forward progress, nor even to go backward, all he can do is continue to tread water.

Llewyn returns to the Gorfeins, and at first there is some relief in returning to his status quo. His meltdown from last time is water under the bridge, and the couples’ cat—Ulysses!—has returned home in the meantime. When Llewyn leaves the next morning, he blocks the cat’s escape and prevents a repeat of the past week’s odyssey to nowhere. Yet soon enough it becomes clear just how trapped he has become. A comment from one of the Gorfeins’ guests about “Please Mr. Kennedy” suggest the song is going to be a hit, and thus Llewyn gave up the money and recognition he’s been chasing when he hastily took the payout. The owner of the Gaslight off-handedly remarks that he fucked Jean, revealing that the entire reason for taking the cash—Jean’s pregnancy—wasn’t even actually Llewyn’s problem. His frustration boils over, but the only outlet he has is the midwestern middle-aged woman performing onstage, probably the most authentically “folk” performer there. He heckles her to tears, which leads to him getting the shit kicked out of him the following night by her husband—bringing the movie full circle back to its opening, the image of a folk musician getting beaten up that was the Coen Brothers' original inspiration—while inside a yet-unknown Bob Dylan takes the stage, the final, cruelest cut to Llewyn’s aspirations. Not that he notices; with a hangdog smile he regards the departing husband in a cab with a wry “Au revoir.”

The tragicomedy of Inside Llewyn Davis’ last act, with Llewis’ cash and karmic debts coming due just as he tries to take steps to escape his predicament, is both its biggest departure from literal reality but also where its bite is deepest and feels the most true. An arts career takes so much active effort to sustain that abandoning it is straightforward enough; one simply stops and does something else. And indeed if the movie was content in just being a portrait of defeat it could have well ended with Llewyn hoisting anchor and leaving it all behind, disillusioned and disenchanted. But that would be too pat, simply the mirror image of the just-so biopics, promising failure rather than success. The Coen Brothers are many things, but they are not pat.

If Llewyn were a great folk musician, then his failure to succeed would read as merely sad, a loss both for him and the world at large. As he is instead not good enough, the calculus is more complicated. It may still be sad, but in a lower, more quixotic register. Our sympathies can only be directed away from the music itself and to its maker, who is seemingly doomed, as Jean warned, to remain stuck turning everything he touches to shit. The editing of the movie suggests that the week’s cycle, starting and ending at the Gorfeins’ and getting beat up in an alley, will continue. It is a grim outcome; Llewyn did not invest his identity into his music to end up okay but not great. Yet such is the fate of most artists. Quality is subjective, of course, and the connection between what is good and what is financially successful is tenuous at best. But most, including many of the success stories, will reach a point where they have to face that, to a greater or lesser degree, the life they imagined is not the one they got.

For me that came less than a month after completing my graduate program. I had my MFA, but I was broke and burnt out and had no concrete idea of what to do with it. I had gone in wanting to make money as a writer, ostensibly in the film industry, and this time to actually make stuff. Now even if I’d had the money to get to L.A., I didn’t want to climb the ladder to a writer’s room, and I didn’t want to become a hired gun for studio garbage. I had hoped that school would clarify my goals beyond ‘make a living,’ which is the artistic equivalent of having a kid in order to get direction in your life. Now I was done and I still just wanted to make my own dark, weird stuff, but was now could more clearly not see a lot of money here.

The final straw was the failure, a few weeks after graduation, of a fundraiser for a too-long short film I had been developing throughout my second year of school and had boxed myself into launching prematurely. It would have been embarrassing except nobody was paying attention, so instead it was merely crushing. In itself this was just another dead project among a dozen, but I had pinned all my post-graduation hopes on it, and without it there was nothing. I was the dog that caught the car, which then slammed on the brakes.

By the time a novel coronavirus shut the world down less than a year later, I had done no new dramatic writing, not that any theaters were open then. I spent most of 2020 at home trying to keep myself busy and stave off depression by exploring other creative outlets: game development, 3D modeling and animation. By June it came time to start looking for work. Months passed without any success, and with my savings running out I was going to have to consider going back to restaurants or into retail. When I got the opportunity for a normal office job in late fall, I took it. If my old career hadn’t died of burnout, it was now certainly dead of COVID-19. It was time for something new.

V. I Been All Around This World

That was three years ago. Of the many differences from then, the most important may be mental; for the longest time I considered myself a playwright first. Whatever job I was doing to survive was a necessary evil that I increasingly resented and felt I had to negotiate with for time to do the real work. Hating the thing you spend most of your waking hours doing is a bad way to be, but I had just taken it as a given that that’s what it took—the price of passion. Stephen King wrote in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft that “Life’s not a support system for art, it’s the other way around,” and for most of the time I was trying to be an artist I had indeed gotten that equation backwards. I mortgaged personal satisfaction for financial comfort, which is like cutting out your tongue to pay for a steak.

I still love Inside Llewyn Davis for all of its many virtues as a film that I have otherwise not touched on: Oscar Isaac makes the viewer see the inside of someone who is so outwardly off-putting, the rest of the cast is just as good, and for how heavy it is it also just as often hilarious. ("Who wrote this?") But watching it now I feel a bit on the outside looking in. I'm no longer in a morass of creative regret, feeling life pass me by. I'm on a regular schedule. My downtime is fixed, and it is up to me what I do with it. I’m still working on creative projects, but without the burden of career expectations I can enjoy the process without trying to build a train track in front of me. Although I am not writing plays and screenplays anymore, I still lend my time and support to helping writers. I have been seeing movies and writing lengthy reviews of them for over a year. I’ve enjoyed it, done it consistently, and received enough encouragement to now formalize it and, well, start a dedicated review and criticism newsletter.

I’ve always been an opinionated person, and while I still think my plays had potential, I knew even when writing them that their characters were often secondary to their arguments. Good writing is straightforward and honest, and making characters play-act a sociopolitical schema is neither. If were still in a depression spiral I would scourge myself and uncharitably say that it's easier to criticize things than make them, which it is—for me. I think anyone who cares about art and media in some capacity, which is to say everyone, has competing impulses to consume, to critique, and to create. Most people comfortably settle into the first of these modes, as the audience, while others have to navigate some mixture of the three. Part of why my plays never went anywhere was that the analytical side of my brain would inevitably short-circuit the inventive side, poking holes until the entire endeavor was sunk. A related problem was that despite efforts to plan and contain scope, I could always think up new ways to make the thing bigger and better. Clearly some things have not changed, but having complete control over the form of the work that text offers makes it easier to bring it back around. As a nice bonus, now people actually get to read what I write.

As much as he could have perhaps made a good critic, Llewyn Davis is not able to escape his cycle of torments—but I can. Anyone can. I’ve loved this movie since I saw it over a decade go for the honesty of its depiction of a life in the arts on the skids, and I hope I’ve done it justice in trying to be equally honest here. Career stagnation and failure isn’t a topic anyone really wants to talk about for obvious reasons, but I think social pressure, sunk cost fallacy, and the terror of the unknown leads a lot of people to try to stick it out in positions that never paid well and no longer even satisfy, and that’s no way to live. Especially after the past few years, a lot of people are in a state of vocational dysphoria. I would never tell someone to give up their passion, but neither would I want them to think they can't do anything else because they've told themselves they shouldn't. People in the arts hear enough about what they should be doing, the last voices that should telling them that is their own.

Some are able to do the legwork it takes for the career they choose. Others end up walking a different path. One of those community theater shows I directed back home, Edward Albee's The Zoo Story, has a line: "Sometimes it's necessary to go a long distance out of the way in order to come back a short distance correctly." The quote loses some of its air of dorm room wisdom when you consider the character saying it is a menacing, antisocial freak, but the point still stands. I may yet find my way back to dramatic writing. For now, though, I’ll follow my feet and just exist. It’s not so bad.

If you want to dig still further into Llewyn Davis, be sure to check out the companion essay, a look at how it fits the Coen Brothers' moral universe, by way of its music.

Member discussion