Fetch Club

This week's missive started off as a joint review of both the original Mean Girls and the threemake that opened this weekend. I had more to say than I expected, though, so I'm separating them. The review of the new movie will go out Wednesday. For now, here's my read on the original.

Everyone has their What How List, the classic movies they have not seen which makes people go "What? How??" when they find out. My most memorable moment of experiencing this incredulity was my first day of teaching introductory screenwriting to undergrads. My admission that I had never seen Mean Girls was regarded with such shock and disbelief that it probably undermined their confidence in my professorial authority. Alas Mean Girls is indeed a Millennial touchstone that I missed out on in its heyday and never caught up with, even after getting roasted by my students.[1] When I learned a new Mean Girls was coming out, I knew there would be no better time to finally cross it off the list. I approached the old movie like its protagonist: naïve and open-minded. Which is all well and good, but it turns out what the movie needs I no longer have: the sensibility and immediate experiences of an early 2000s high schooler.

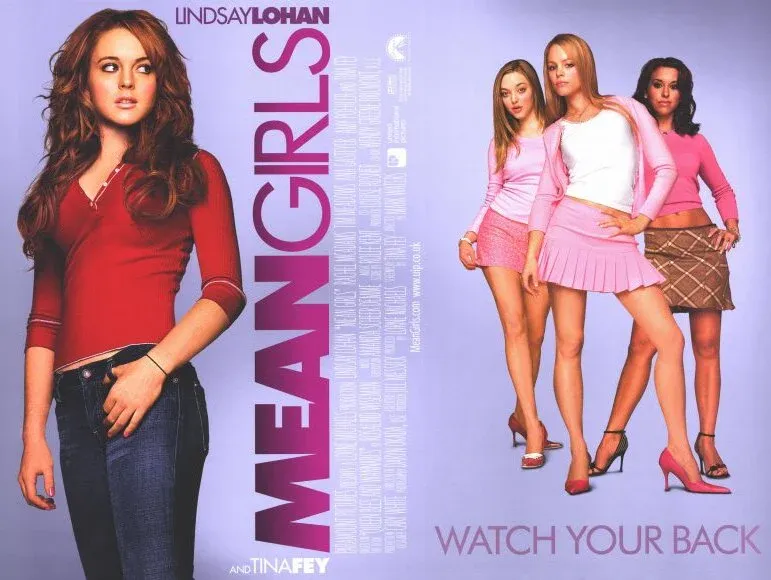

The movie is so well-known that a plot summary is practically beside the point, but I know what it’s like to feel like the only person who had never seen it, so: Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) grew up homeschooled while her parents did wildlife research on the African savannah, but when they decide to return to the U.S. to teach at Northwestern University, she is enrolled at a public school, North Shore High. There she is befriended by two misfit art kids, sassy gay Damien (Daniel Franzese) and caustic maybe-lesbian Janis (Lizzy Caplan), who give her a primer on the school’s various cliques. At the top of this hierarchy sit the Plastics, a trio of pretty rich popular girls led by the witheringly cruel Regina George (Rachel McAdams). Regina takes an amused interest in Cady, who has no experience with the mores of American teenagers, and takes her under her wing, with Janis and Damian encouraging her to be wary but also report back on the Plastic life. It is not long at all before Cady falls for Regina’s ex-boyfriend Aaron (Jonathan Bennett), going so far as to pretend she doesn’t know how to do math in order to get him to talk to her. This leads Regina to spitefully take Aaron back, setting Cady on the path to revenge.

‘Humor is subjective’ is a critical escape hatch meant to soften the blow of not connecting with something beloved by millions, and I’ll get to that, but I will say I do understand why Mean Girls became such a quote mine. The screenplay is stuffed with one-liners and funny business, with laugh lines dropping at a rate of something like every five seconds. Even as I’m not a fan of what that all does or doesn’t add up to, I appreciate the volume of jokes packed into the movie’s 97 minutes, the effort in making sure the audience gets the bang for their buck. Many of these lines have been continually quoted and referenced ever since: “Stop trying to make fetch happen,” “Get in, loser,” “She doesn’t even go here!” Similar to Heathers a generation before, Mean Girls strikes a nerve because it gets right at the Darwinian stratification of high school life. Its thesis is right there in the title, mean girls, and articulated by its meanest girl, Regina. Rachel McAdams plays her as a terrifying apex predator, with big, intense eyes communicating menacing intent and a top-teeth-baring grin whose breadth makes you understand why chimps interpret this as a sign of hostility. Regina's hissable villainy is delightful, rightfully star-making stuff, and holds the entire movie together.

And the movie does need some holding. Lindsay Lohan makes for a sympathetic anchor, but I find Cady to be a bland protagonist. She is upstaged by not just Regina but also Damian and Janice, and her passivity makes her transformation into a mean girl two-thirds of the way through the movie unconvincing. Also unconvincing is how after this the movie immediately back-pedals into a happy humanistic ending, in which the artificial social divisions of North Shore High School are torn down and the Plastics join other cliques. We are supposed interpret the story from Cady’s perspective, from a point of innocence, but the overall view of the film itself, separate from the world it takes place in, feels, well, mean. Tina Fey’s race problems are well trod ground at this point, and it feels like stepping into a trap to get offended by edgy jokes from an edgy era. But the way the school’s divisions are cynically described by Janice (“Asian nerds, cool Asians… unfriendly black hotties”) leaves a bad taste. The script’s rapid-fire quippy style has the drawback of leaving the actors little to play but shtick, which is detrimental to the non-Plastic characters and gives the non-white actors little to do except play their reductive types with as much energy as possible. Tim Meadows’ sick-of-it-all principal is the exception, while Amy Poehler as Regina’s equally plastic mother is the rule, and I have no idea what to do with deluded sex-crazed Indian wanksta mathlete Kevin Gnapoor, though I am happy to learn his actor Rajiv Surendra has found inner peace as an artisanal craftsman. The movie would not have improved by giving us a touching scene of Kevin G giving Cady some yarn he had spun like Surendra did for Tina Fey while they were shooting, but just including some details that played against type would have gone a long way toward making the movie’s theme of mutual understanding, which is literally delivered as after-school special message, more credible. As it is, no one in the movie, not even Cady or her parents, knows which country in Africa she is from, so it all rings hollow.

This makes sense given the movie’s origins. Mean Girls was an original script, but it was inspired by Rosalind Wiseman’s 2002 nonfiction parent guide to teen girl bullying, Queen Bees and Wannabes. It would be a stretch to call the movie an adaptation, but it is enough of a derivative work that Wiseman was paid $400,000 for the film rights.[2] And yet despite that anti-bullying messaging and framework, Regina is far more sharply observed than the ignorant outsider Cady. Tina Fey subsequently admitted to being a bully in high school, and in the publicity for the new movie says she identifies most with chip-on-her-shoulder Janis, that in high school she "talked a lot of smack," and that abrasiveness comes through in the writing. This isn’t inherently bad, writing mean is fun, but it doesn’t gel with the script’s more wholesome origins and outcome.

“Your fave is problematic” is not an original or even useful observation, as it mostly functions to foreclose engagement rather than foster it, and I am willing to consider context. Rude, elbow-throwing humor was the dominant mode of comedy in 2004. That was the year of Team America: World Police, and back then I ate that shit up (so to speak). And I would certainly have been more receptive to Mean Girls when I was still fresh out of high school and not wondering if I'll be attending my 20 year class reunion. But as it is, while I appreciate the craft and the acting, its humor just no longer does much for me. Yes, finally, humor is subjective, and comedy as a genre also ages faster than any other. I’m not surprised that one which passed me by 20 years ago, when I was the age of its target audience and characters, did not work for me now. I am actually bummed to have missed it at the time when I would have been most primed to enjoy it and gotten the two decades of shorthand it begat. It is of its time and can be understood as such.

Yet surely if Mean Girls were to be done today without the weird racial baggage, it would be the best possible version of itself, right? Get in, losers, we’re going to the movies.

In my defense, when the movie released in April 30, 2004, my town’s only movie theater had already closed for good months before. To this day the nearest theater is still a 40 minute drive away. Not great! ↩︎

Wiseman last year threatened legal action against Fey and Paramount Pictures for unpaid net profits, but the new movie’s release was the springboard for a New York Times profile last week, so they seem to have worked out their differences. ↩︎

Member discussion