Thin Grool

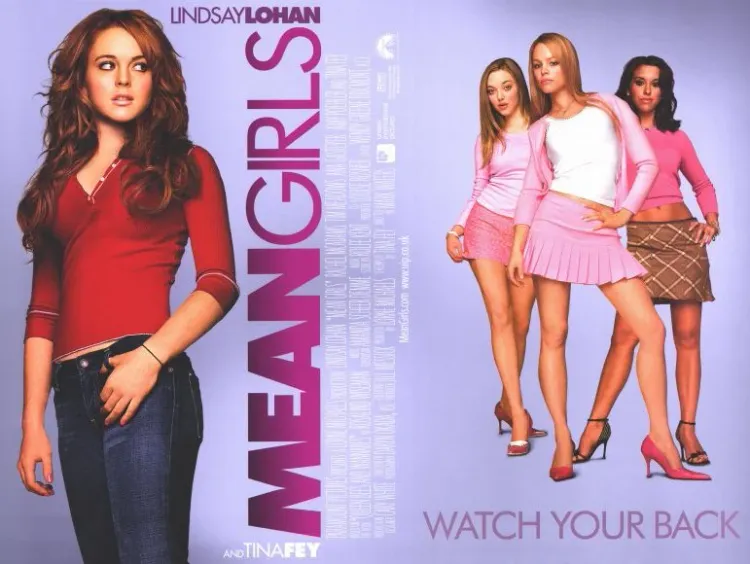

The second half of my Fetch Quest is here! If you haven't already read my review of the original Mean Girls, check out it out.

In a world where the Mattel Cinematic Universe slouches toward Barbieland to be born and every character that was popular in the 80s and 90s has a nepo baby sequel, a new version of the hit 2004 comedy Mean Girls is almost refreshing. No tortured continuity, no ridiculous geriaction scenes, just a familiar story retold in a different register. Not regurgitating the same old thing isn’t the same thing as making a good movie, however. The 2024 Mean Girls doesn’t embarrass itself and is broadly enjoyable, but in smoothing out the original’s edges it has mostly been left without a personality or purpose of its own.

The broad contours of the plot for the two movies—Mean Girlses?—are the same. Cady Heron (Angourie Rice) grew up homeschooled while her mom—dad is out of the picture now—did wildlife research in Africa, now specified as Kenya. Mom returns to the U.S., Cady is enrolled at North Shore High School, art students Damien (Jaquel Spivey) and Janis (Auliʻi Cravalho), give her the rundown. Regina George (Reneé Rapp) and the Plastics rule the school, Regina amuses herself with Cady’s child-like ignorance of teenage socialization until she shows interest in Regina’s ex Aaron (Christopher Briney), at which point Regina snatches Aaron back and Cady plots with Janis and Damien to bring Regina down.

Despite what the rather misleading ad campaign has implied, this is not a straightforward remake of the 2004 film. True, this is not your mother’s Mean Girls (the lede for the trailer which surely turned half the original’s fast-approaching-middle-age Millennial audience to dust); it is instead an adaptation of the 2018 Broadway musical adapted from it. The throughline is Tina Fey, who wrote the screenplay for Mean Girls and played math teacher Ms. Norbury, then wrote the book for the stage musical (her husband Jeff Richmond wrote the songs, with lyrics by Legally Blonde: The Musical’s Nell Benjamin), and has here written the new movie’s screenplay and reprised the Ms. Norbury role.

The original movie was distinctly Fey’s comedic voice; a musical is a different, more collaborative animal, and a movie musical different still, and so while the dialogue still contains a lot of audience-favorite quotes along with some new quips, the script on the whole has been finessed to meet the needs of its songbook. Some of the grosser plot elements have been excised; a subplot about a creep gym teacher preying on a couple Asian girl students is gone, and where before Principal Duvall (Tim Meadows, also returning) spent much of the movie leering at Ms. Norbury, they’re now in a down-low relationship that’s played rather sweetly. Kevin G (last name changed to Ganatra, played by Mahi Alam) has been reined in, though he’s still rapping and ripping his shirt at the end. The school’s racial divisions have been dropped or de-emphasized, the only identity group called out being “the Christian believers,” which perhaps says the most about how much has changed in two decades. These are all mostly welcome changes, but they are surface-level; the problems with the story remain, and now also contend with the movie’s shortcomings as a musical and reinterpretation.

The songs are standard modern Broadway fare: twee head-voice vocals and jazz-hands excitability, the kind of thing that comes to mind when you think ‘hyperactive musical theater kid.’ The arrangements are mostly in a kind of bubblegum punk style that incorporates clean guitar or electronics as needed. It’s easy enough to listen to, if not especially memorable. The way the songs are deployed are generally effective, happening during the pivotal story moments. Several have been doled out to the supporting cast, with both of the other two Plastics given one to flesh them out. Gretchen (Bebe Wood)’s “What’s Wrong With Me?” functions well enough as a setup to her being “fragile” and apt to give up information later on, but in the moment feels extraneous and slows the story to a halt. Karen (Avantika)’s “Sexy,” about enjoying Halloween for getting to be someone else while still being hot, is one of the better numbers and could in theory represent an interesting shift from 20 years ago in how female sexuality is regarded by the mainstream. But with lines like “This is modern feminism talking/I expect to run the world/In shoes I cannot walk in/I can be, who I want to be,” it’s hard to parse what the song is actually trying to say about such outfits.

Unfortunately Cady being a wet noodle carries over to her songs, which feel small even when she’s joined by other cast members like in “Revenge Party,” where she and Damien and Janis plot to bring Regina down. The rest of the cast is generally good, with Jaquel Spivey’s Damien being the most entertaining to watch, even if he is even more like Umbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’s Titus Andromedon than the character was before.

The staging of these numbers is inconsistent. Some get a full dancing ensemble within the reality of the film, while others resort to fantasy sequences to do so. Some play around with the lighting and staging, as with “World Burn,” when Regina, vowing to get back at Cady is bathed in a satanic red strobes; others get a bland, music video montage treatment. There are some intriguing uses of the portrait-mode single-take visual language of TikTok, but it’s only occasionally applied. That inconsistency carries over to the movie’s direction and aesthetic more broadly. Regina’s house benefits from its rich décor and garish pinks, but otherwise there’s nothing stylized in the locations that isn’t a part of the world already, unless it’s a fantasy sequence. The costumes are mostly non-descript, with the Plastics dressed so dissimilarly in their introduction—a dorky sweater, a colorful top piece, and a black biker jacket—that it’s impossible to believe they are all part of the same clique. Eventually they do switch to pink, which is an improvement but does make for some cognitive dissonance, what with the villainesses being dressed like they’re going to a showing of Barbie.

I did not very much like that movie, but it did at least have a point of view, or several it was trying to reconcile. Here certain lines (again, "This is modern feminism") gesture toward it without really saying anything. There’s a moment where Ms. Norbury grouses to Cady, “Homeschooled! Oh, that’s a fun way to take jobs from my union…. No, I’m joking.” It’s a laugh line, mostly sold by Fey’s rictus grin delivery, but what’s the joke, what’s the desired audience response? Is it ‘Haha yes, homeschooling does starve the union, that’s bad,’ which would be a weird priority but okay—or is it ‘Haha, of course the teacher cares more about her union than the student’s education,’ which is the position of conservative Christian-led efforts to destroy public education? This kind of satire—which is hardly exclusive to Tina Fey, it’s endemic to Saturday Night Live—doesn’t have a point of view, it just tosses out references to issues and assumes the reference is itself the joke.

The original Mean Girls’ point was straightforward enough, even if it wasn’t entirely convincing: high school girls can be viciously competitive, and they shouldn’t be. The movie made the first half of that message with a triumvirate of carnivorous Barbie dolls sitting at the top of its hierarchy. But if high school in 2024 is still a social Darwinist deathmatch of strictly enforced hierarchies, it’s not clear where these lines are drawn, and how they’re enforced. Why do the Plastics think they are better than the other students? I want to say ‘class,’ and Regina’s mother (Busy Phillips[1]) strikes me as the kind of homeowner who would want to keep those people out of the neighborhood, but there is nothing to indicate that these people are bad beyond being a little catty and maybe kind of dumb.

Perhaps the biggest example of this problem is Regina. Like Rachel McAdams before her, Reneé Rapp is best in show, getting all the best songs and putting personality and some actual vocal power behind them. She carries herself with a devil-may-care cool and a magnetism that the movie and the music goes all in on: her introduction song, opening with “My name is Regina George/And I am a massive deal” is, in theory, a boast that should mark her as a self-absorbed princess. But the leather jacket, the mystique of her direct address with the top of the screen cutting off her eyes, the slow and sultry delivery, the dirty electric guitar—she’s not baring her fangs, she’s waving her feathers.[2] She says she’s a big deal, and the movie doesn’t disagree. The Regina here is someone to be worshipped, whereas the Regina of the original movie is to be feared. McAdams delivered her lines with a tossed-off cruelty and a Kubrick stare, whereas Rapp turns a line like “Get in, loser” into a neg, if not an outright flirt, peering over her sunglasses and giving Cady and the viewer a come-hither glance. It would be fun to imagine Regina being driven by sexual jealousy rather than status if there were anything at all in the text to support it, but that takes us pretty far astray from the cruel sport that was the original movie's secret appeal.

‘The best part of the movie doesn’t understand what it’s supposed to be about’ is a weird place for Mean Girls ’24 to be, but maybe that shouldn’t be surprising. Only a relative handful of properties have gone the movie-to-musical-to-movie-musical route, and the big ones (The Producers, Hairspray, and Little Shop of Horrors, by my reckoning) were based on relatively obscure films and so could focus, with highly varying results, on capturing the things people liked about an ephemeral stage show for posterity. In this case the musical is not that great, while the original film has only become more culturally entrenched, and other teen movies have been able to apply its lessons to today's sensibilities.[3] And so the new Mean Girls ends up a decontextualized imitation, less mean and more meme. Though the title is still correct, in a sense: as math nerd Cady would be the first to point out, ‘mean’ can also mean ‘average.’

Who I genuinely think is an upgrade from Amy Poehler; Phillips treats the character having peaked in high school as not (just) a joke, but a sad fact of her life whose implications she is constantly trying to keep at bay. ↩︎

This should be a problem for a movie about high schoolers, but Reneé Rapp, who played Regina in the Broadway show in 2019 and is now 24, does not look at all like a teenager, nor does the rest of the 20s-aged cast. Which is bad for the cinematic illusion but good for, I don’t know, perverts? ↩︎

Last year's Bottoms in particular is so much more relevant, stylized, irreverent, and funny than this. ↩︎

Member discussion