Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake: Revisionist History

Greetings friends! The Hideo Kojima retrospective continues apace, with the first of many Metal Gear sequels, one which remains an impressive and important title, the earliest of Kojima's that one both can play and wants to play.

Also, the latest episode of my movie podcast with Steven Santana, Mise en Screen, is now live! This week we talk spoiler-free about A24's hasty re-release of Chinese animated movie Na Zha 2 into theaters, along with related titles good and rotten. Tomorrow we drop an additional spoiler episode, including an in-depth discussion on China's growing role in the entertainment industry. Subscribe on your favorite podcast service!

Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake

(dir. Hideo Kojima, 1990 for MSX2)

July 8, 2020 translation patch by Nekura_Hoka and Takamichi Suzukawa

I. Found in Translation

"Possibility Space," a term popularized by Sim City creator Will Wright, refers to the array of options given a player within a game. It presupposes player agency, the ability to choose, but within narrow parameters and resulting in narrower outcomes. In the fiction of a game these decisions are usually present-tense and future-oriented—if I do this, then that will happen—though they are an arguably under-used tool for positing alternate histories: if she had done this instead of that... well, then what? Even the most complex game is an abstraction of a vastly more complicated real world, which is less a possibility space than a contingent one, subject to a near-infinite number of variables whose significance can only be glimpsed after the fact, with knowledge of the outcome.

Contingency gave us Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake. The first Metal Gear was ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System for the American market, and despite compromises in gameplay and presentation required by the hardware, it sold well enough for Konami to develop a sequel, Snake's Revenge. The company did this without Hideo Kojima's knowledge, and as he tells the story it would have remained so were it not for a chance encounter on a train with another Konami employee whose division was working on the game. The unnamed employee didn't think much of it and suggested he make a proper sequel instead. Kojima thought on it and that night sketched out a concept, with work on the new game commencing not long after. Although it's possible that Kojima would have eventually revisited his first game, the confluence of these several variables resulted in the Metal Gear 2 we got: a more complicated and polished possibility space than the original, one that became the template for its even more ambitious sequels.

II. The Front Line

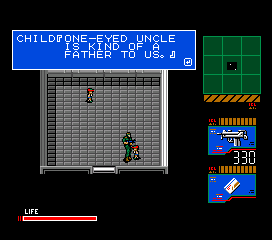

The game laps its predecessor in every way. The sneaking mechanics have been built out, with Snake able to crawl and hide beneath structures, and the patrol/alert binary of the guards revised to include a cooldown 'search' period before returning to patrol. A map has been added to the UI, allowing the player to see enemy movements on adjacent screens in eight directions. Although the weapons are largely the same, the number of tools and their uses are vastly expanded, making for a greater variety in puzzles and solutions. Metal Gear 2 may not have left RPGs, simulations, and adventure games behind to make a new genre of "comprehensive entertainment," as Kojima and the game's manual boasted, but it did take the best parts of them and create a title that still plays well today.

Being a stealth action game, it does not contain the volumes of text and detailed illustrations that the adventure title Snatcher did, but nonetheless the presentation also received a significant upgrade. Illustrated cutscenes bookend the gameplay, with radio and in-game dialogue that is short and to the point. This in itself is something of an accomplishment, as cutscenes created for the first Metal Gear had to be cut for space considerations. There's variety in Masahiro Ikariko's chiptune music to fit the game's moods and stages, though it mostly lives in a cool military futurism. Kojima and his team, including Isao Akada and Toshinari Oka on game programming and Hiroyuki Fukui on demo programming, applied everything they had learned in making Snatcher across three disks, and took small but important steps towards Kojima's hybrid cinematic ideal.

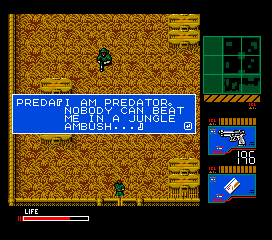

Beyond just having more items that look better when they are used, they can be used in different ways and contexts. Early in the game you come upon a control room with a view of the base. There's nothing useful or interactable in the room except two guards, but when you enter some music begins to play: the Zanzibar Land national anthem. The two guards stop and stand at attention, allowing you to take them out. On its own it's a neat little bit of world-building, but there's more: later on you get ahold of a tape deck that plays the anthem, a little piece of the world now in your control. If you play the anthem when there are guards around they will all stop and salute, which is extremely handy in a bind. If you use it too many times, however, the tape audibly warps and wears out and becomes unusable. This isn't realistic in the sense that it accurately models real-world behavior, but it makes the game world believable because it is responsive, with a quite long chain of action and reaction.

Yet for all the increase in player agency, the narrative of Metal Gear Solid 2 is an authored, contingent one. That tension will become more fraught in future titles, but here Kojima is working on a canvas still small enough to require him to be economical. The story here too is defined by contingency rather than possibility, its characters living in the shadow of the previous game's events as much as the turning tides of real-world politics.

III. New World Order

Ever the optimist, Kojima premises his game on an almost utopian world order. It is 1999, the Cold War is over, and so too is the nuclear standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. The nuclear powers have begun to decommission their stockpiles. Before utopia can take hold, however, an oil shortage sparks a global energy crisis, one that only looks to be resolved with the development of Oilix, an energy-producing microbe engineered by Czech scientist Dr. Kio Marv. No sooner has Oilix been announced but Marv is kidnapped by agents of Zanzibar Land (not to be confused with the Tanzanian island archipelago Zanzibar), a rogue nation formed in former Soviet territory between Russia and China that is also raiding and pillaging those countries' nuclear stockpiles. With Oilix and an increasing nuclear arsenal, Zanzibar Land is set to shatter the brittle peace, and so FOXHOUND dispatches its greatest operative, Solid Snake, to rescue Dr. Marv. Before long Snake learns Zanzibar is building a new Metal Gear prototype that poses the biggest threat of all to global stability.

It's a more detailed setup than the original game—too much so. The energy crisis angle complicates the backstory, similar to the plague in Snatcher, but it doesn't ultimately matter beyond the premise and would be ignored in the 1998 sequel. Oilix's main function is to provide a target for Snake to spend most of the game trying to rescue, which could have just as easily been done by focusing on the nuclear weapons from the beginning. For what it's worth, Kojima has said that the original premise was a raid on a nuclear facility but that was considered unrealistic; this would end up being the setup for Metal Gear Solid.

All the same, the game's premise is interesting for how it reflects the time it was made. Metal Gear 2 was developed at what Francis Fukuyama ambivalently called The End of History: the Berlin Wall had fallen , and while the Soviet Union was still a year away from dissolution, it had retreated from large-scale ideological conflict. Political and/or economic liberalism had taken root among the developed nations, and so the age of contests between great powers seemed to have passed. Fukuyama's original 1989 essay is sanguine about the world to come, more than he tends to get credit for:

The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one's life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.... Perhaps this very prospect of centuries of boredom at the end of history will serve to get history started once again.

He would later add, in a book-length expansion of the essay,

Experience suggests that if men cannot struggle on behalf of a just cause because that just cause was victorious in an earlier generation, then they will struggle against the just cause. They will struggle for the sake of struggle.

In the real world this would indeed play out, in the ideologies Fukuyama himself considered and dismissed: religious fundamentalism, nationalism, idle warmongering that Fukuyama himself would support, and a revenant fascism. Yet this takes us afield from the Metal Gear series. For all their geopolitical intrigue, the games, and Kojima's work in general, very rarely deal with nuts and bolts politics and ideologies. Instead they abstract political struggles to more simple, universal ideas. A post-nuclear world order is one. "Struggle for the sake of struggle" is another, and the most important one to Metal Gear 2.

IV. Meet the Big Boss, Same as the Old Boss

The original Metal Gear ended in triumph. Solid Snake, then a rookie FOXHOUND member, successfully infiltrated the terrorist base Outer Heaven, rescued veteran soldier Grey Fox, destroyed the bipedal nuclear battle tank Metal Gear, and defeated his own commanding officer Big Boss, revealed to be the terrorist leader, before escaping from the self-destructing base. It was pure action heroism, down to Snake escaping with explosions going off behind him.

The Metal Gear Solid series now is infamous for its convoluted lore resulting from later retcons, yet the revisionist approach is already present in this very first follow-up.

Metal Gear 2 casts a shadow across that victory. The first boss Snake encounters is revealed to be one of his old comrades, the resistance leader Schneider. A radio ally in the first game, he was implied to have been killed after learning Big Boss' secret, but here he tells of being unable to escape Outer Heaven–which did not self-destruct but was bombed by NATO, killing resistance members, women and children. Petrov Madnar, the reluctant inventor of Metal Gear, became all too willing to advance his dread creation after finding himself without research opportunities in the wake of worldwide nuclear disarmament. We learn Snake himself has been plagued with nightmares since Outer Heaven, just before the final battle with Big Boss, who is very much not dead. The first Metal Gear's story, such as it is, has been almost completely refuted.

With these retcons the game establishes an important precedent. Hideo Kojima would become famously ambivalent about continuously returning to the series, squaring this by revising the backstory as needed to suit his current thematic and narrative interests, and assuming there would be no sequel. The Metal Gear Solid series now is infamous for its convoluted lore resulting from later retcons, yet the revisionist approach is already present in this very first follow-up. Here the changes serve the game's fatalistic mood, embodied in the heel turn of former FOXHOUND legend Gray Fox.

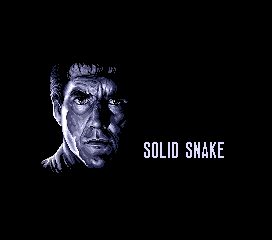

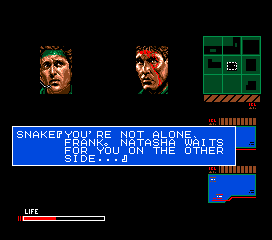

Although the game bears Solid Snake's name, it is Fox—the only codenamed member in the series to also retain his real name, Frank Jaeger—who is given the most development. One of the few allies you contact in person is Natasha Marcova (changed to Gustava Heffner in the later official localization), a former Eastern Bloc Olympic figure skater turned intelligence agent. She reveals she had been in love with Frank and wanted to cross the Berlin Wall to join him, but the West refused her asylum and, now branded a traitor, she had no other choice but to join Czechoslovakia's STB intelligence agency. Not long afterward Fox makes his entrance piloting a new Metal Gear, blowing up a bridge and mortally wounding Natasha, with neither of them realizing the irony of their situation. Later he faces Snake, first while piloting Metal Gear and then hand-to-hand. "Dying in battle suits me," he sniffs afterward, telling of a lifetime in combat zones that left him unable to be a part of normal society. It was for that reason he accepted Big Boss' offer of a life of unending battle. He is but the model citizen of Zanzibar Land, which is crawling with the orphans of yesterday's wars, whom Big Boss will send to fight the wars of tomorrow. Fox functions as a cautionary tale for Snake, who will shortly confront Big Boss and repudiate his vision of a world that will never know peace.

V. From an Era of "Entertainment" to an Era of "Experience"

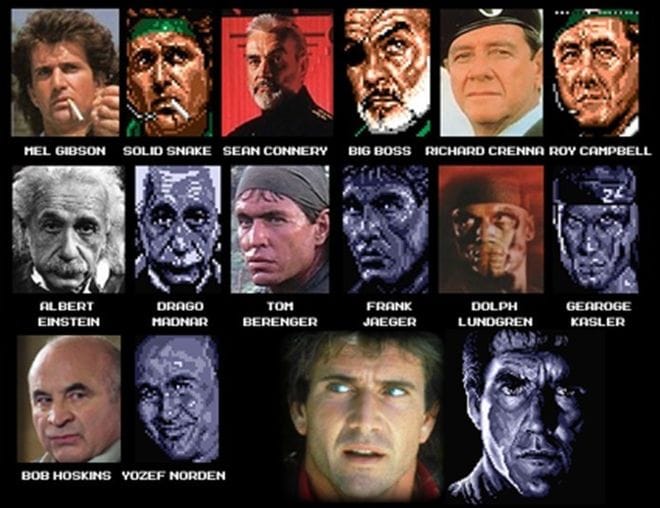

The final words between Snake and Fox are conveyed only in text and a couple heads, but Fox's fatalism and bloodied Tom Berrenger-in-Platoon headshot does a lot to evoke the post-traumatic despair of The Deer Hunter (from which Snake's bandana is taken). Stolen valor? Perhaps. As with Snatcher Kojima is using imagery from his favorite movies as shorthand for the effect he's going for, but it's in service to some genuinely compelling ideas. The real world did not face so heightened a scenario as a rogue nation stealing the world's nukes and energy–privatization in post-Soviet Russia and blowback from mujahideen-controlled Afghanistan was plenty–but if Hideo Kojima did not anticipate world history this time around, he did anticipate his own. The topics of war orphans, nuclear war, and whether a soldier can escape their own circumstances, would come up again and again in future Metal Gear titles. The game is ultimately simple in its treatment of the issues it invokes, simple even for a neocon like Fukuyama, but their presence and number bespeak a desire to break down, in its own awkward phrasing, "the Berlin Wall inside our minds," separating fact and fiction, cinema and games, player and character. I'm more moved by the attempt at emotional resonance than I am by the melodramatic results, but I appreciate the advances being made in that direction.

Over a decade after its initial release, Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake would be ported along with the original game to Japanese mobile phones and then to the Playstation 2 internationally, as bonus content for the Subsistence expansion of Metal Gear Solid 3. Among other modernizations it replaced the celebrity headshots with new stylized character art. This made it more more consistent with subsequent entries, but the game lost some of its aspirational texture. Metal Gear 2 is a good game, good enough that its sequel was structurally a 3D remake, but it didn't just want to be good. "Comprehensive Entertainment," that was the goal, encompassing and surpassing everything that came before, and nothing conveys that like The Hunt For Red October's Sean Connery in an eyepatch telling Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon that he will never be able to suppress his killer instinct.

Hideo Kojima's entertainments would grow ever more comprehensive. In 1992 he would give Snatcher a wild concluding act on more powerful hardware. He would then build on that game's exploratory adventure foundation to deliver his biggest attempt yet at an interactive movie, complete with animated cinematics—a Lethal Weapon to surpass them all.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion