Oscar Clickbait

Greetings friends! With the Academy Awards concluded I'm about wrapped on 2024. Along with a write-up of the ceremony I've put together my reads on the best of the Best Picture nominees, Nickel Boys, The Brutalist, and I'm Still Here, along with a write-up on the results and links to nominees for live-action and animated shorts.

I Want to Spank the Academy

Half the fun of following the Oscars is complaining about the Oscars. My biggest complaint about Sunday's ceremonies was an old one: their habit of bringing up the music to force award-winners to wrap up their speeches. This is always bad, but it was especially galling considering how much time was given over to nearly twenty minues of tributes to James Bond and Quincy Jones. The best Oscar ceremonies are the ones with minimal bullshit, and that should be the producers' lodestar every year.

The actual results were surprisingly hard to predict, which made them fun to watch. There was enough split between Wicked, The Brutalist, and Anora, with Conclave as a dark horse candidate, to make it an unpredictable night. Flow winning Best Animated Feature was a very nice surprise, and I'm Still Here, along with being an excellent movie, is even more impressive for getting Best International Feature when few people had even heard of it two months ago.

The biggest snub was baked in: Nickel Boys was not nominated for Best Cinematography, and even though it was very good in other respects, the first-person visuals led the conversation on the movie. Without recognition of that there was no foundation for Best Adaptation or Best Picture, and so it took home nothing.

The speeches by No Other Land filmmakers Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham calling for an end to the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, the return of October 7 Israeli hostages, and a political solution that accepts the dignity and national aspirations of both peoples, was brave and clear-headed. It made Adrian Brody's later speech, rambling, somewhat self-pitying, ending with a mealy-mouthed call to stop hate, even more embarassing.

Morgan Freeman's tribute to the recently departed Gene Hackman was quite moving. That David Lynch received only a wordless third billing on the In Memoriam section was very strange (non-Lynchian) for how widespread was the mourning after he passed in January, especially because he died from being evacuated from the L.A. fires which were referenced several times in the ceremony. Michelle Trachtenberg wasn't mentioned at all, despite being well-known for her characters on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Gossip Girl. For Millennials of a certain age, however, she was a 90s Nickelodeon fixture. I'll always remember her as Little Pete's best friend (and Iggy Pop's daughter) Nona Mecklenberg on The Adventures of Pete and Pete.

I had a great time with Anora when I saw it, and even said I would be happy for it to be the only other picture besides Parasite to take both the Palme D'or and the Oscar. (I also lamented that at the time Anora co-star and underrated pillar of the Sean Baker Cinematic Universe Karren Karagulian still didn't have a Wikipedia page, so I'm going to take credit for this.) It's still a terrific comedy, but having seen most of the other nominees (A Complete Unknown and Wicked held little interest, and it's not like I'm getting paid for this), my immediate thoughts feel hyperbolic in retrospect. I'm not eating my words, but I am nibbling. Here's why.

Short-Changed

Nickel Boys

(dir. RaMell Ross, 2024)

The thing everybody is talking about with Nickel Boys is that 'it uses first-person perspective,' and while that is an easy enough summary, it also obscures what makes it more than just a gimmick. The change in POV brings with it a number of choices that have to be made about movement, focal length, staging of scenes and more, as the assumptions in place with third-person shooting and editing can no longer be taken as given. These have all been thoughtfully considered by director RaMell Ross, and the result is remarkable.

The omniscient camera is not normally assumed to have a POV, even though shot selection implies directorial intention that shapes audience response. The first-person camera is in fact a character, here two of them, close friends Elwood and Turner, who meet at the hellish Nickel Academy reform school in 1960s Florida. A lot of thought has gone into how they see the world, what they want and don't want to see. It does this and yet still manages to also look frequently beautiful, the long lenses creating more intimate image, soft focused to give it the gauzy feel of a memory. Which it is: although these shots are all 'one-er' single takes, the scenes are not minutes-long marathon takes of an ongoing experience the way life is lived. Instead they unroll elliptically, jumping forward and backward in time. Adding to this are various movies, home videos, and other media of the time, and then still another visual scheme, this time a third-person camera set behind Elwood during scenes that are set decades later in the 1980s, when he is played by Daveed Diggs.

This third-person camera is not so immersive: it is clearly harnessed to the actor from behind rather than being positioned there, it follows his motion with every minute turn he makes, and so the visual language is less traditional film than third-person action video game, which sacrifices all compositional elegance in favor of mere readability, a nonissue for a non-interactive medium. These shots do not present the same harmony of character and camera that the first-person shots do, but it's not clear that they are supposed to. We do eventually get a 'hand-off' from first to third person, with an inference of its cause and meaning. I won't discuss the specifics of it, if only because Nickel Boys has been rather scandalously under-seen. But the Elwood of the 'present' day is traumatized and even decades later in a state of dissociation, having closed himself off from the intensity of feeling he once had. From a content-dictates-form standpoint, the psychological collapse informs the aesthetic collapse.

A recurring act in the first-person shots are other characters making eye contact, looking head-on into the camera. This has been compared to characters in a first-person game doing the same, your Skyrims and Bioshock Infinites, but that is to undersell the power of live-action and the human face. Directors from Yasujirō Ozu to Spike Lee have utilized direct address in isolated shots, to communicate accusation or to break the fourth wall and consider them as people and not just characters. To do so in a sustained fashion really does create a kind of radically direct empathy with both the POV characters and their second-person interlocuters, whose gazes bore into the viewer without the distancing of a third-person framework. It's impossible for a subjective camera to embody the full experiece of a perspective, the body language, facial expressions, inner thoughts, contextual associations, but Nickel Boys still conveys what it is like to move through its particular world, with all its attendant love and terror.

A Shorts Interruption

Predicting the Oscars shorts is always a crapshoot, but this year's animated winner In the Shadow of the Cypress was the obvious standout, using appealing and sometimes poetic visuals to tell a story of overcoming wartime trauma. Beautiful Men was also trying to be more than just cute (Yuck!, Magic Candies) or edgy (Wander to Wonder), but it was obviously too weird to get enough votes. I do admire it for its full-frontal male puppet nudity. The moment in the ceremony where the Iranian filmmakers lost their spot in their Google-translated acceptance speech was sweet, a highlight of the night.

For live action I had pegged A Lien to be the winner for the political salience of its ICE entrapment story, but this year's ceremony was light on politicking. The actual winner, I'm Not a Robot, is amusing and well-made, but really does feel like a one-panel New Yorker cartoon stretched to twenty minutes, the weakest of a solid crop. The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent is tense and ends with one of the most wrenching dedications I've ever seen. Anuja is built around a good relationship between its two sisters, but it ends on an ambiguous note that I'm not sure works for a short. For me the clear champ was The Last Ranger (no online viewing option unfortunately), which boasts African landscape and wildlife photography, a lush John Powell score, and a title character who feels positively mythic as a defender of endangered wildlife from the depredations of man. It ends up also being timely, for showing us that the worst person in the world right now is a white South African wielding a chainsaw.

Concrete Meanings

The Brutalist

(dir. Brady Corbet, 2024)

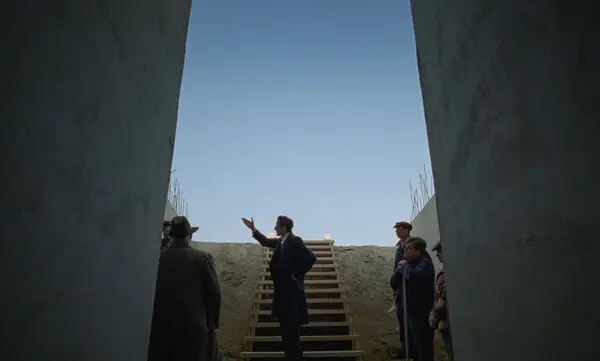

The idea of an Oscar Movie has shifted in recent years, but in the collective unconsciousness there is still the related notion of the Great Movie. The kind of grand, timeless, monumental work that we can point to and say, 'like this.' For the IMDB crowd this would be The Godfather, the older generations have epics like Gone With the Wind or Lawrence of Arabia, for the hardcore cinephiles it's the works of Tarkovsky or Béla Tarr: huge in scope, meticulous in their craft, not without humor but sober-minded and unsparing in their depictions of human folly and vice, often operating in a tragic mode. The Brutalist has all the trappings of a Great Movie and is richly satisfying as such, but there's a certain self-consciousness around the edges that threatens to undermine its ambitions. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

For all its grandeur, the scope of the story is quite intimate. At its center is the relationship between Jewish-Hungarian architect László Tóth (Adrian Brody) and wealthy industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pierce), who hires Tóth to design a monumental community center on the outskirts of postwar Philadelphia. This allows him to bring his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) and niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy) over from Europe. It's a human-sized drama which serves as load-bearing pillar for weighty themes like the postwar immigrant experience, artistic integrity, and the founding of the state of Israel. The architecture theme allows its visuals to go big, highlighting the smallness of its figures amid titanic concrete structures, and director Brady Corbet's sundry formal touches—an overture, the division of the story into chapters, ornate modernist-styled title cards, an intermission, shooting the film in VistaVision—give the movie the feel of an old-school epic. It's a pastiche of a classic film, not as slavish imitation, at least not entirely, but as subversion.

This isn't fully clear at first. While the first act does introduce some complicating factors—tensions with Tóth's assimilated American cousin, his patronage of brothels and heroin dealers—it is for the most part a straightforward portrait of The Immigrant Experience, at least as collectively remembered by the children and grandchildren of those who landed on Ellis Island: starting with nothing and through toil and sacrifice working one's way toward respectability. The movie plays it straight enough that I wasn't sure while watching what the importance of this was supposed to be. Then the second act begins, the dominoes set up begin to fall, and the movie reveals itself as a curdled repudiation of the American Dream. There have been dark, ironic approaches to the immigrant subject before—it's the subtext of nearly any ethnic gangster movie, criminal empires as the true road to success—but the ruin of an honest striver feels novel, especially for a movie aiming for prestige. It is as if the aspirational immigration of An American Tail was crossed with the predatory industry and postwar dislocation of Paul Thomas Anderson's Americana panoramics There Will Be Blood and The Master.

Like the former, The Brutalist has a time-jumping final act that involves a surrogate child who doesn't speak which threatens to break the movie. The epilogue here doesn't have an instantly meme-able monologue, in fact the difficulty in parsing it comes from the fact that Tóth does not speak for himself. Instead we are given a very pointed read on everything we have just watched, one which so goes against most of what we have seen that we have to wonder if we're supposed to take it seriously. And then the movie ends with a grotesque false cheer so left-field that it is impossible to do so. It scrambles any reading one might have had to that point and reminds the viewer that this is indeed directed by the guy who made Vox Lux.

It will take another watch to consider the rest of the movie in light of these last few minutes. I'm a defender of pieces that mar their otherwise perfect construction in pursuit of a vital idea the work could otherwise not contain, and I'll be doing it again shortly. On first viewing the ending of The Brutalist felt like a middle finger to anyone who took the drama at face value, and I'm still not sure that isn't the case. Even before that the movie is withering in its attitude toward American optimism. At a certain point, north of three hours, one yearns for some positive notion of what all this is supposed to be for.

Which is what the last scene is for, horrible as that positive value may be. Perhaps that final moment is just a postmodern shrug, an insincere and insecure smirk from a director who is afraid to take a stance. Then again, maybe it is an acknowledgement from Corbet that if he had the answers we would be in a better place. The ending is a confounding thing, which probably dashed The Brutalist's chances of a Best Picture win even more than its generative AI controversy. Would it have been appropriate for an ironic attack on respectability politics to win respect, or would that have been more ironic in turn? An achievement in cultural sophistication, or a failed attack on it? Postmodernism can knock out the foundations for grand narratives, but it poses few of its own. And as the epilogue makes clear, in a narrative vacuum, unscrupulous others will rush to fill the void.

Mending the Gap

I'm Still Here

(dir. Walter Salles, 2024)

Dictatorships come in different ideological flavors, but they are at bottom simple: one person calls the shots, his party fires the shots, and anyone who disagrees receives the shots. Something resembling normal life continues for those who don't stray out of bounds, if there is too much disruption the vastly greater numbers of people will become disruptive in turn. But for dissenters, that semi-normal life can easily give way to violence, imprisonment, disappearance, torture, death, all of which in turn becomes another part of life.

I'm Still Here is great for how it conveys this simple truth, by being itself deceptively, devastatingly simple. Telling the story of the family of former Brazilian congressman Rubens Paiva (Selton Mello) and his wife Eunice (Fernanda Torres) after Rubens' abduction by unidentified members of the country's military dictatorship, it foregoes histrionics and polemics in favor of an experiential approach, right down to its period-accurate 35mm and Super 8 film stock. The early scenes are unhurried snapshots, sometimes literally, of the family's life: playing on the beach, young son Marcelo (Guilherme Silveira) adopting a dog, eldest daughter Vera (Valentina Herszage) preparing to study in London. We have to love this family and Rubens in particular in order to feel his absence later on, and Selton Mello shines in these early scenes as a loving husband and father. The warm, lived-in relationships, developed in improvisational rehearsals prior to shooting, are everything.

When the military that is a background presence in the family's life steps to the fore, the movie remains understated, like its characters. It doesn't quite unfold in real-time, but it maintains its unhurried pace, slowly turning up the temperature. It's easier for the plainclothes secret police to take people away by speaking softly, after all. And it's easier for Rubens and Eunice to keep their dignity if not always their lives by treating it just as matter-of-factly. Fernanda Torres is not portraying an emoting victim or a political billboard but a woman who has no other choice but to endure because she has a family to protect, and she is magnetic. Watching Eunice and her kids trudge their way through unknown territory is compelling enough to overcome the narrative becoming less urgent as the movie goes on.

I would have been happy to watch these people for hours more, though there did come a point where I wondered when Walter Salles, who knew the family when he was growing up, was going to let them go. There are a couple points that seem like natural conclusions to the story, yet it carries forward, decades ahead, past the fall of the military dictatorship, far enough that the family are all played by different actors. It jostles the otherwise perfect pacing, and we do lose the performers we've grown attached to. But as I said above, sometimes it's better to be true than perfect, and the ending of I'm Still Here is necessary to its ultimate purpose: it is a portrait of a family, in the most literal sense. It will change, become unrecognizable, but... well, it's right there in the title. That's another simple truth: the best revenge against a dictatorship is outliving it.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion