Policenauts: The Future is Unwritten

Greetings friends! It's been a minute, hasn't it? Life and various obligations have kept me from doing much writing here. I'm doing weekly movie reviews for the Mise en Screen podcast, so for the time being I'm going to focus on seeing my Hideo Kojima retrospective all the way through. (The most recent episode covers Angel's Egg, the newly restored surrealist anime directed by Kojima's friend, Ghost in the Shell director Mamoru Oshii.) This time we examine Policenauts, the most obscure of Kojima's games and where technology begins to catch up to his filmic aspirations.

Policenauts

dir. Hideo Kojima, 1994, 1996

Played on Sega Saturn via emulation (Beetle Saturn)

2016 English translation patch by Marc Laidlaw, Artemio Urbina, and Michael 'slowbeef' Sawyer

I. The Boom Generation

In a recent column for the Japanese women's magazine An-An, Hideo Kojima wrote of the Osaka Expo 70, a 1970 festival of world culture and futuristic optimism that was a formative experience, his own "B.C. and A.D." He compared it unfavorably to the 2025 Expo, which did not inspire in him a similar sense of wonder. The exploratory committee had sought his input in 2020, he says, but they did not have the money to realize his ideas. What those ideas involved are unspecified, but we do have copious examples of how Kojima has envisioned the future before. All of his games except for the Metal Gear titles that take place in the past are speculative fiction to varying degrees.

Policenauts is perhaps the clearest look we have at what he imagined the future to be. Though it trades in the kinds of conspiracies that would soon become his signature, it presents a vision built on the optimism and technology of the Space Age in which the Osaka Expo took place. Policenauts was in its own time futuristic, using the newest technology available, refining Snatcher's adventure game design, and converting the anime-influenced pixel art into actual cel animation. Yet there is much about this that Kojima would never do again, making it something of a path not taken, an intriguing glimpse at an alternate future.

II. Crew Up

As far back as the production of Snatcher, Kojima was thinking about space travel and its effect on the human body. It wasn't until after the release of Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake in 1990, however, that he could begin working on what would become Policenauts. In December of that year journalist Toyohiro Akiyama, accompanying Soviet cosmonauts on the Soyuz TM-11 mission, became the first Japanese person to go into space. This created significant interest in NASA and space in Japan and brought the concept of the game into focus. As would become his standard, Kojima also took inspiration from various topics and news stories that piqued his interest, in this case Japan-bashing in the wake of the movie Rising Sun and ethical debates over organ transplants of brain-dead patients.

Several of Kojima's key future collaborators came on board during Policenauts' production.

By year's end he had scripted and storyboarded most of it but was transferred to another department within Konami, from Planning to Technical Training, which delayed production. In all he would be transferred three times in six years while working on the game and its various ports. The scripting and flagging language previously developed for Snatcher was further refined, allowing him to plan much of the game out independently, to control the timing of dialogue, animation triggers, and transitions.

Which is not to say he made the game by itself. Several of Kojima's key future collaborators came on board during its production. Noriaki Okamura directed system design and programming; he would go on to direct the Kojima-produced Zone of the Enders and, having stayed with Konami after Kojima's departure in 2015, is now the Metal Gear Solid series producer. Kazuki Muraoka came on for sound design, and Kazumitsu Uehara for programming. Late in production the most important of Kojima's creative partners was hired, artist Yoji Shinkawa, though his responsibilities here were largely debugging and revising the mech art.

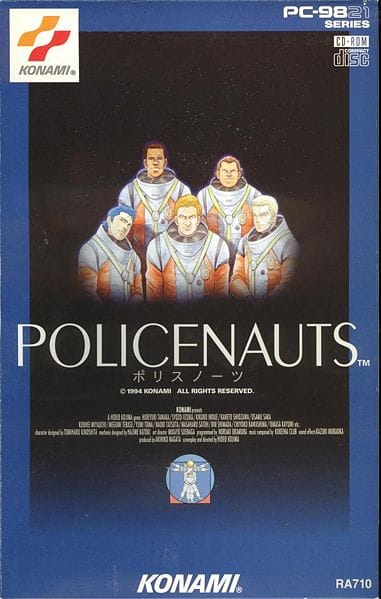

Collaborators were not the only new part of development. Leaving the 1980s tech of the MSX2 behind, the new game (originally titled Beyond, which proved to be un-trademarkable), would be developed for the PC-9821, an update on the popular Japanese PC-8800 series of computers that used CD-ROM technology. By this point Kojima had worked on the 1992 PC-88 port of Snatcher, the basis of the later American Sega CD version, but that was essentially a higher-definition remaster. With mouse control, greater storage and memory capabilities, and CD-quality sound and music available from the go, Kojima was able to make his most polished attempt yet at marrying the presentation of cinema with the interactivity of games.

III. Ars Technica

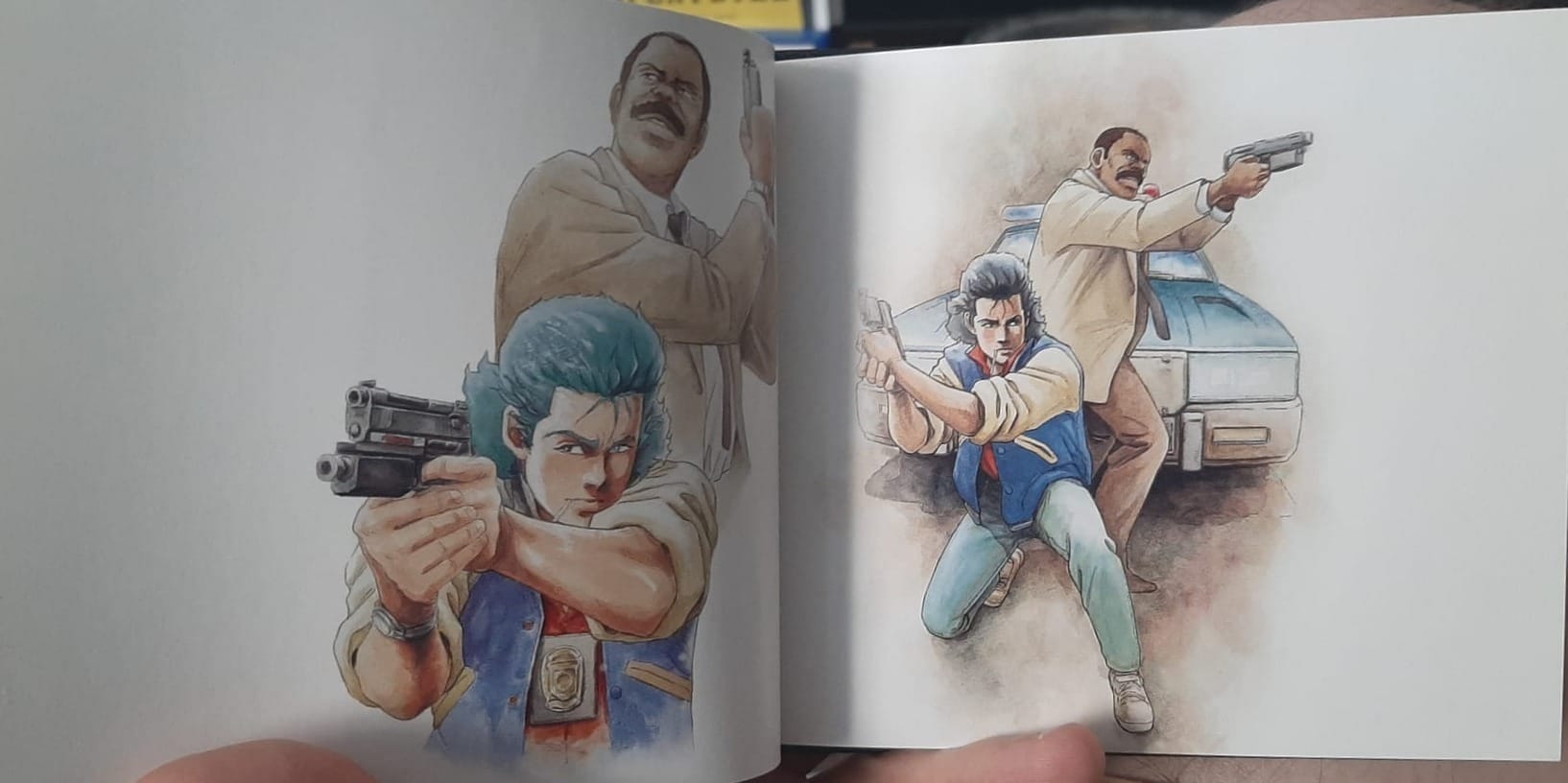

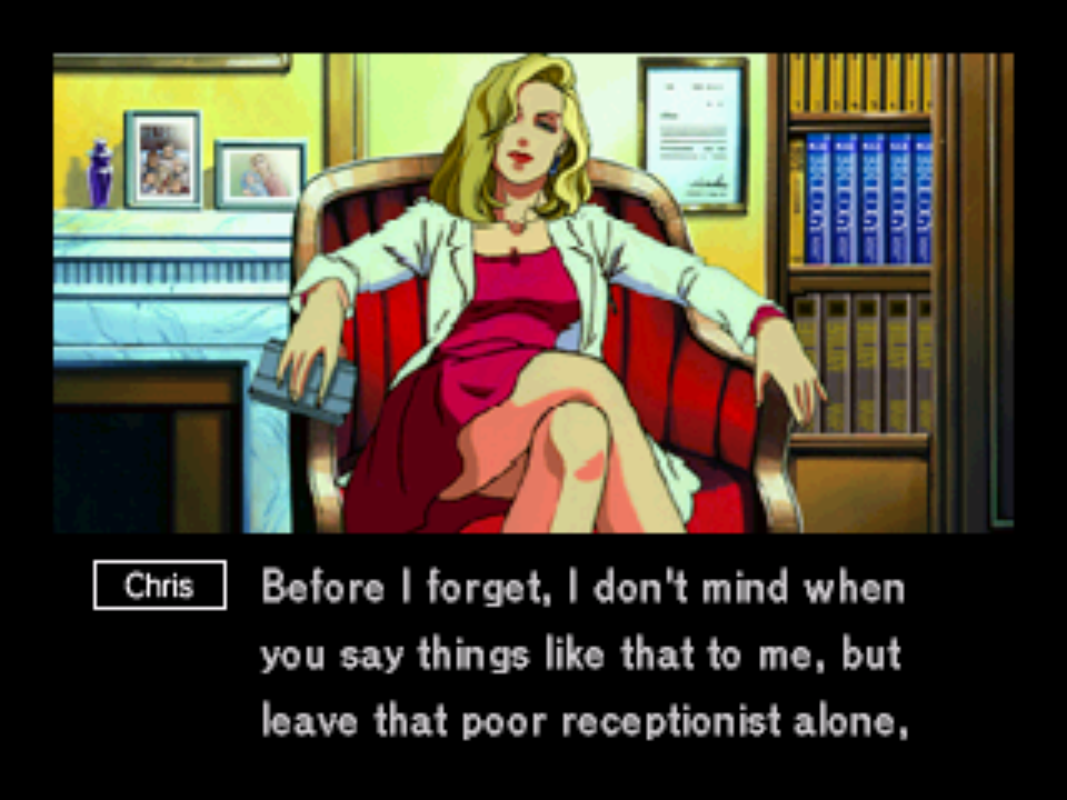

Although later ports of Snatcher would get fully voiced dialogue, Policenauts included it from the start, requiring new skills and workflows. The game's visual inspirations were, as ever, American movies and TV series—Lethal Weapon most obviously, but also Starsky and Hutch—and so when casting Kojima looked for actors with dubbing experience. Hideyuki Tanaka, Jonathan Ingram's voice actor, had done dubs of Michael Biehn in The Terminator and Aliens, and Jonathan's ex-wife Karen's voice actor Kikuko Inoue even dubbed the Rika van den Haas character in Lethal Weapon 2 a year before Policenauts' release. Recording took six days, in part because the actors couldn't record their lines together.

The PC-98 edition received no patches or updated releases adding captions, which has hamstrung efforts to localize it up through the present day.

Extensive, professional voice acting was still a novelty in games and best practices had not been established, and so Policenauts' original PC-98 release did not include captions in cutscenes on a first playthrough. An outcry from players who were hard of hearing led to all future ports of the game being captioned. The PC-98 edition remained as is, however, with no patches or updated releases adding captions, which has hamstrung efforts to localize this version up through the present day. More's the pity, as the advancement in visual presentation in subsequent ports is a mixed success.

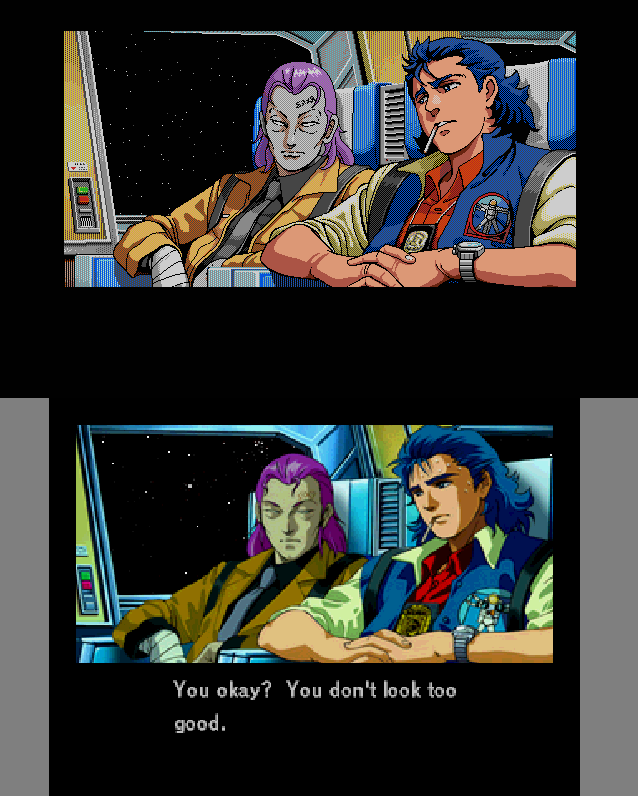

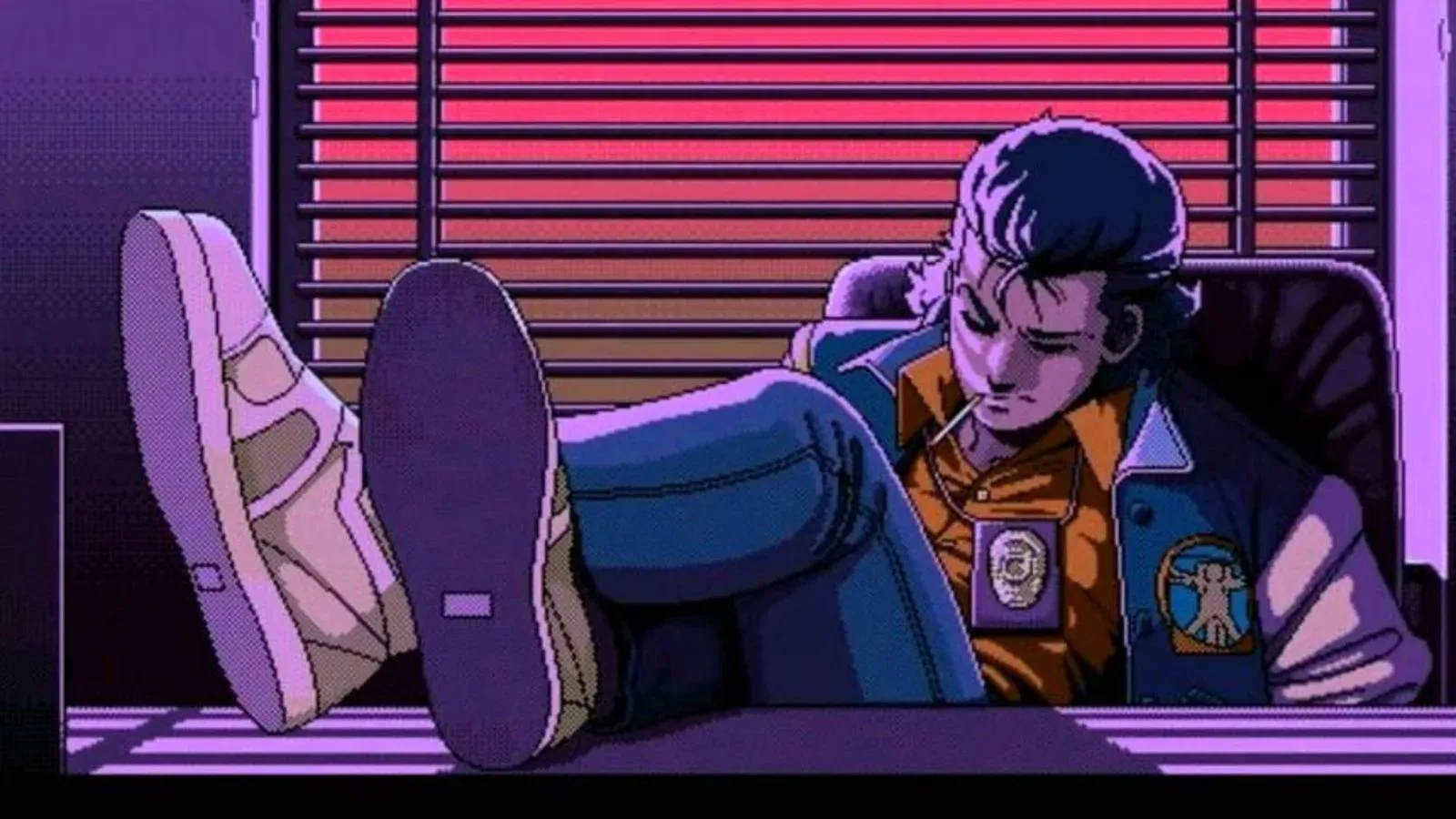

The graphics of the PC-98 edition are all pixel art: crisply rendered in 640 x 400 resolution, and actually benefitting from the unusual decision to work within the limitations of the earlier PC-9801 to only display 16 colors at a time rather than the PC-9821's 256. As with Snatcher's various incarnations and Metal Gear 2 they have few animated elements, but their dynamic direction more than makes up for it. But for the console ports, starting with the 3DO and continuing to the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn, the cutscenes and slides were re-drawn and animated in cells by Anime International Company, known for the OVAs Bubblegum Crisis and Ah! My Goddess! The crossover between interactivity and hand-drawn animation is exciting, yet the effect is compromised; CD storage was limited, and in order to fit them the resolution was cut essentially in half, down to 320 x 240, making for a less detailed and more pixelated image.

It's an unfortunate compromise, though not one that a mid-90s console player would have minded. Narrative-driven games were mostly confined to RPGs, which were still enjoying a console heyday on the previous generation of hardware; Chrono Trigger was still new by the time the PlayStation version of Policenauts came out, and Final Fantasy VII was still a year away. Cutscenes and dialogue in next-gen games were functional at best, clumsily grasping for cinematic visuals. Policenauts not only looks like something you might watch in the cinema, it has the confidence to kick off with the audio of you would hear, a female announcer as was once typical of Japanese theaters:

"Thank you for your patience. And now, our feature presentation. Enjoy the show!"

IV. Space Odyssey

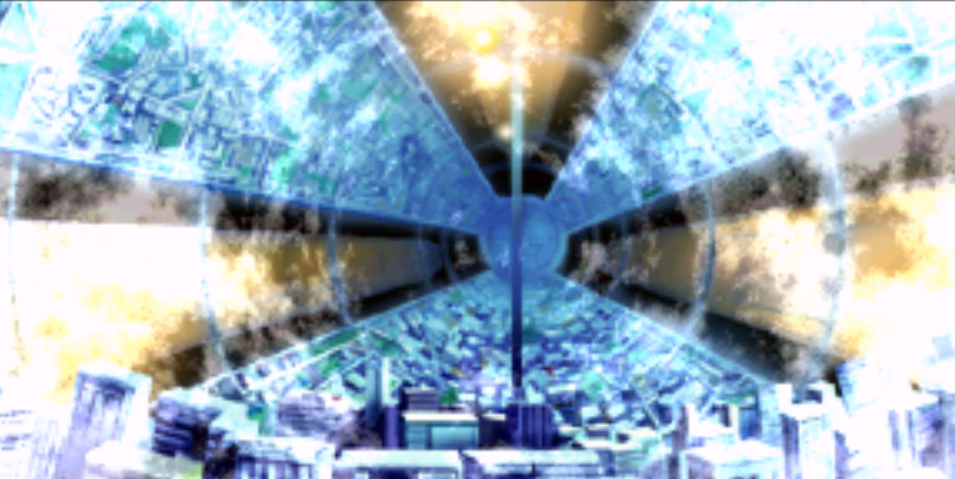

In the future of 2013, space travel had advanced to the point that construction of the first space colony, Beyond Coast, was completed. Providing security for the fledgeling station were a team of Earth's best law enforcement officers, trained as astronauts. Jonathan Ingram of the LAPD was one of them and was performing routine maintenance when a malfunction sent him flying off into the outer reaches of space. His life support unit saved him but put him in suspended animation, in which he remained for 25 years until being discovered and rescued.

Three years later Jonathan is back in L.A. making ends meet as a private detective on missing persons cases. Into his office steps his ex-wife Lorraine, whose Beyond Coast scientist husband Kenzo Hojo has gone missing; she feels Jonathan is the only person she can trust to find out what happened. Jonathan would just as soon never go into space again and turns her down, but after she is killed in a car bombing outside his office he resolves to go to Beyond Coast and find the culprit. At the Beyond Coast Police Department he reunites with his old partner Ed Brown, banished to irrelevance in a basement vice unit office with his officers Meryl and Dave, who offer their help to Ed and Jonathan in investigating Lorrain and Hojo's deaths. They need all the help they can get, since the BCPD, run by erstwhile Policenaut Gates Becker, operates at the discretion of the colony's dominant conglomerate Tokugawa Pharmaceuticals, headed by another former comrade, Joseph Tokugawa.

It's a solid premise, though marred in the execution: Lorraine's death feels like a cheap shock, given the dramatic potential of her interactions with a still-young Jonathan and the silliness of a villain using such literally bombastic methods to cover up a conspiracy. It is conventional, for better or worse.

For all its cosmic scope, this is by far the most grounded of Kojima's plots.

So far, so Snatcher: an adventure game with visual designs pulled straight from Kojima's favorite movies, where you play as a detective estranged from his wife and with no recollection of the future world he finds himself in. Policenauts has been criticized as being, at best, a refinement of Snatcher's formula, and it never does quite break out of this framework. The shooting segments control better but still feel tacked-on, and the exploration/navigation is still more about exhausting menu options than figuring out the correct answer.

But as exciting as Snatcher's original and later iterations were as new frontiers for Kojima and adventure games, their execution left definite room for improvement. The Blade Runner and Terminator inspirations were too directly lifted to give that game a visual identity of its own, and the pacing is lopsided, with two acts of open-ended puzzle solving and dialogue trees giving way to a strictly linear third act. Policenauts is more linear overall, but it is much better about parceling out the secrets behind its world.

And indeed Beyond Coast might be the most fully-realized world that Kojima has ever created. The shuttle Jonathan takes to the colony functions like an airliner, with standard passenger protocols for space adaptation sickness. He arrives on a massive rotating O'Neill cylinder orbiting around Lagrangian point L5, which the in-game glossary helpfully notes is, "where an object can theoretically maintain a stable orbit due to the gravitational forces of two larger objects." The Tokugawa Pharmaceutical offices occupy a skyscraper that extends up into the central point of Beyond Coast, where its centrifugal gravity is weakest and VIPs like to party. There are copious amounts of descriptive detail given over to Beyond's three waves of immigration from Earth, referred to as 'Home,' and the difference in accents and outlooks in colony- and terrestrially-born individuals.

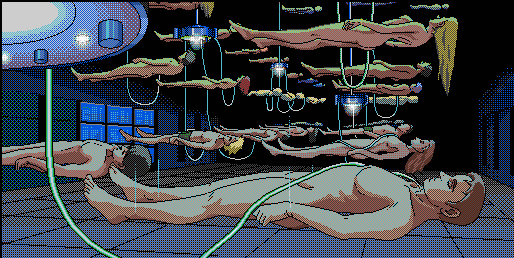

The extensive world-building, using real-world scientific concepts, is crucial, since the story is about that world. Typical of the detective stories which are Kojima's biggest narrative influence, one crime reveals another, which reveals another still, and at its heart is an organ-harvesting operation designed to meet the demands of Beyond Coast's population, which suffers increased levels of cancer and other by-products of long-term exposure to the sun and the inhospitable conditions of space. Policenauts' villains behind this plot are not given all that much psychological shading, yet their primary motivation of outer space exploration feels weighty by dint of being born of an enthusiasm shared by Kojima himself. The game is awash in wonder at scientific achievement, yet it concludes with the sober realization that sustaining humanity in a place it was not made to be requires, well, inhumanity. For all its cosmic scope, it is by far the most grounded of Kojima's plots.

This also means fewer of his characteristic acknowledgments of the fourth wall. There are copious references to Snatcher and the Metal Gear games, though not so many nods to the player. There is an infamously difficult bomb defusing puzzle, of which Jonathan asks, "What kind of sadistic fuck came up with this?" and if the player fails and blows up and then tries again, the action resumes thus:

It is the most accomplished game Kojima had done to this point. Reviews of the 1994 PC-98 release are impossible to come by on the English-language internet, though we do know the 1996 ports scored highly in Weekly Famitsu and Sega Saturn magazine, which praised it for its story and presentation. At least one American outlet, Hardcore Gamefan, covered the Japanese PlayStation release, and a couple French magazines also gave it high marks. Otherwise most international players only knew of it from brief references in Metal Gear Solid in 1998, and it would remain that way for over a decade. Even today, getting to play Policenauts is an adventure in itself.

V. Beyond Home

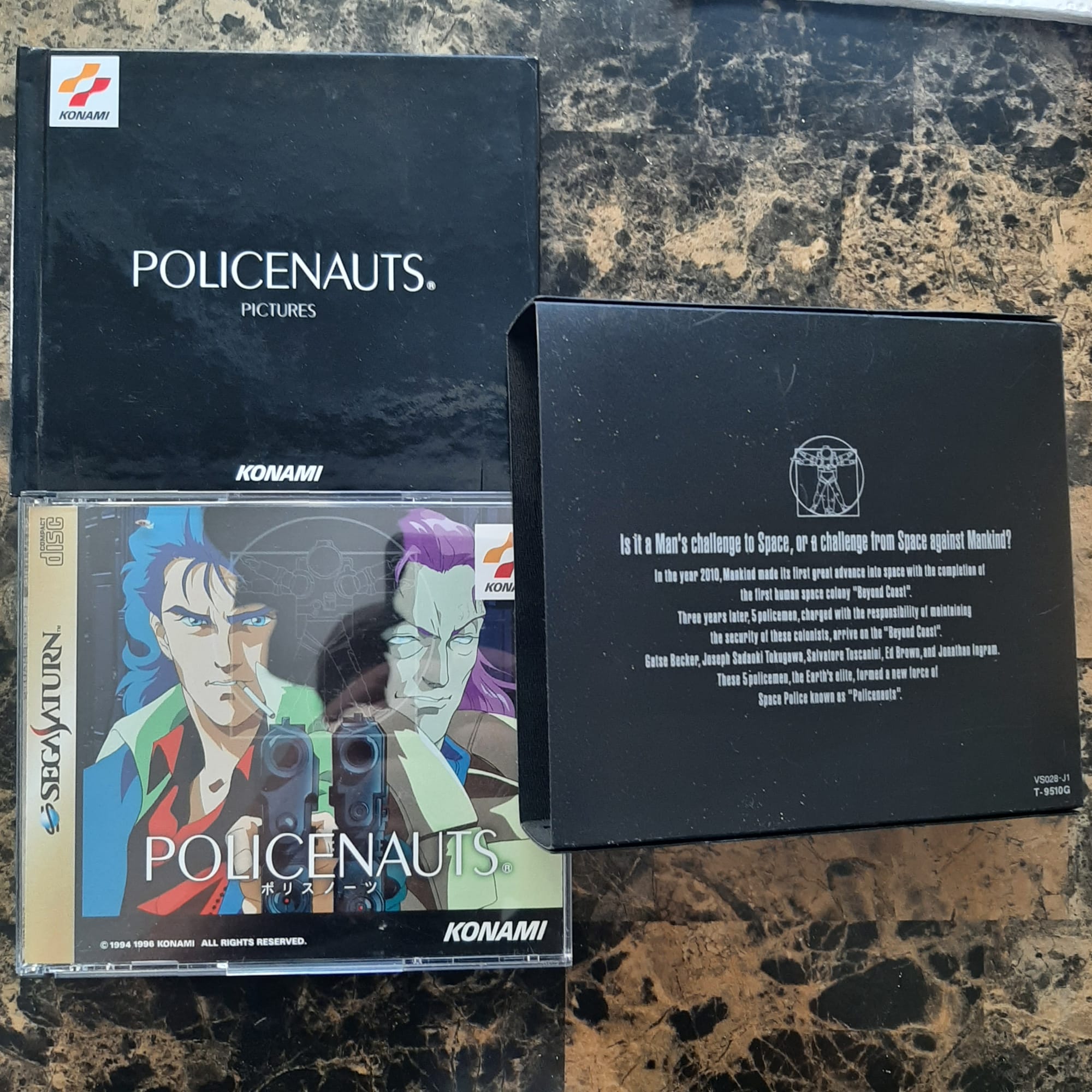

For years western audiences had no way of playing Policenauts. It was never officially localized, reportedly due to dissatisfaction with the game's lip-syncing tools. When asked about a re-release in the wake of Metal Gear Solid's success, Hideo Kojima said he wasn't interested in returning to older titles. A fledgling email campaign to Konami was waged in 2003 to no avail, one year after work began on a fan translation of the PlayStation version began. With the first two Metal Gear games ported to the PlayStation 2 in 2005, Policenauts became the only one of Kojima's early titles not to have some kind of international release. The PlayStation version was re-released for the PlayStation 3 in 2008, but in Japan and nowhere else. The translation had been completed in 2007, but implementation into the game itself was not completed until 2009. Work on a Saturn translation commenced and only released in 2016.

Many elements of Policenauts would be referenced in Metal Gear Solid and its sequels, and some were re-used wholesale.

Widely considered the best version, the excellently translated Saturn port is the one I played, though not without difficulty. Saturn emulation is more demanding on a computer than the PlayStation, and setting it up involves placing some specific files with specific names in specific folders. If anything is out of place it just doesn't work, with no explanation. Patching the English text into Policenauts involves a similar song and dance. Once set up I encountered no problems, until literally the last five minutes, when a specific cutscene would fail to load every time I got to it. I had to ditch the old, unsupported emulator I had been using and figure out how to switch to the more stable one, and the process involved more specific file management jiggery-pokery. Once that was solved, in order to not have to start the game over I had to find a fan-made tool (KnightOfDragon's Saturn Save Converter), which required an old version of Microsoft's .NET to run, and which could take the in-game saves from the old emulator and spit out files that the new one could read. It was an enormous hassle, albeit oddly gratifying, an antidote to the passive consumption that is the norm in today's media.

Of course this only ends up being 'worth it' if the game is actually good, and fortunately Policenauts is very good indeed. It's Hideo Kojima summing up a decade's worth of lessons learned, and for the first time it feels like his ambitions, skills, and technology have kept pace with one another. Many elements of Policenauts would be referenced in Metal Gear Solid and its sequels, and some were re-used wholesale: plot recaps, the telops used to introduce characters with their voice actors, and the "Doo, doo, doo, do-do doo" beginning of the opening track "End of the Dark," all are now familiar to the MGS player on a Pavlovian level. Other ideas would be further iterated on. The background of clearly-telegraphed henchman Tony Redwood, a genetically-engineered "advanced human" is a clear forerunner for arch-nemesis Liquid Snake. An easter egg that adds additional text if the player has completed save data from Konami's dating sim Tokimeki Memorial: Forever With You would be memorably expanded into a full setpiece for the Psycho Mantis boss fight. Policenauts is the missing link in Kojima's ouvre, the one that shows Metal Gear Solid did not come from nowhere, as American players had experienced it, but was instead building on a sturdy foundation hidden behind a language barrier.

VI. Escape Velocity

Kojima would lend his services to the adventure game genre a little while longer; the code base of Policenauts was used for the Tokimeki Memorial Drama Series spinoff, on which he served as a producer. The first of those games even includes Policenauts as a movie the player can see on a date with. But Kojima later said that making Policenauts showed him the limits of controlling everything on a project. Some of those limits are apparent in the gameplay itself, and even in the visuals; the effect of some of the later plot twist/info-dump scenes is diminished by having a handful of slides to switch between over several minutes. In that light it is not surprising Kojima would never again make another point-and-click adventure.

Even the most perceptive of speculative fiction will fail to account for the full scale of the future and the changes it brings. A fully operational space colony is still a dream, and an increasingly delusional one. Between the 1994 PC-98 release of Policenauts and the completion of the 1996 ports, Kojima had seen the possibilities of the new console generation and 3D technology and was planning on bringing it to bear in another Metal Gear sequel for the hot new console–the 3DO. The immediate future was seemingly clear enough. Yet he could never have predicted how much everything was about to change. Though he would produce and even design other titles, Policenauts—the first to bear the opening credit, "A Hideo Kojima game"—would be the last full-length non-Metal Gear Solid game he would direct for two decades. Another B.C.-A.D. milestone was about to be crossed.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! You can also get more of my movie thoughts, and more frequently, on my weekly podcast with Steven Santana, Mise en Screen. If you know someone who would enjoy either of them, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion