Queer: A Man Apart

Happy new year! And a happy one year anniversary to Cinema Purgatorio, which launched just over a year ago. I won't be quite as prolific as I was at that point, two 2000+ word essays a week is a bit much, but I hope to make up for that with depth, variety, and a little more polish and visual interest. With that in mind, here's a deep dive on Luca Guadagnino's Queer, a film that's grown on me the more I've thought about it and is the only movie I saw twice in theaters last year.

Queer

(dir. Luca Guadagnino, 2024)

Intro. "He always gets some innaresting effects."

To be, or not to be, 'queer?' The term is defined by otherness, a departure from the norm, yet its connotations have been ever aflux. For decades a slur deployed by conventional society, by the 1990s it had been rendered a somewhat passe neutral descriptor, usually of the gay men who were its most visible representatives. In the 2010s 'queer' was folded as one identity among many into an acronym, LGBTQIA, whose syntactic usefulness became inversely proportional to its length.

In the past few years, 'queer' has come back around as a catch-all term for the not-default sex and gender orientations. It does so just in time for Luca Guadagnino's Queer, an adaptation of a William S. Burroughs novela that dates back to the term's derogatory heyday. If the title doesn't quite pack the same confrontational wallop as it would have in the 1950s, it is an apt descriptor of its content, a strange and unapologetic excursion into gay life of a bygone era rendered in modern terms, an adaptation of a book that already adapted from real life, and a heady mix of alienation effects and potent passions.

I. "Just a routine for your amusement, containing a modicum of truth."

The viewer who approaches Queer unfamiliar with its source material may be baffled or, worse, bored. Its story is simple enough: An American expatriate in 1950s Mexico City, William Lee (Daniel Craig) is enchanted and confounded by a younger American student, Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), who returns Lee's affections only to recoil from him afterward; Lee seeks a solution to Allerton's inconstancy in a legendary Amazonian herb, Yage, ayahuasca, rumored to bear gifts of telepathic communication that will bring separate minds together.

Any notion that this will be a straightforward period piece is quickly dispelled by the opening credits, set to a Sinead O'Connor cover of Nirvana's "All Apologies." Nirvana makes a couple more appearances on the soundtrack, along with some choice Prince cuts; and still other blatant musical anachronisms that would have made a superb companion album to Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross' lonely, longing score. The effect is to make the movie both alienating and familiar, breaking the cinematic illusion but opening up a line of connection with Lee, whose perspective the needle drops often serve to highlight. They are as foreign to the time period as he is to Mexico City.

The city itself in turn allures with artifice. Filmed in Rome's Cinecittà Studios, the sets are lavish enough to convince, but DP Sayombhu Mukdeeprom's camera is always finding just-so ways of framing it and using rich colors to make the image pop. Guadagnino has cited Powell and Pressburger's The Red Shoes as an influence, and one can see that vibrant Technicolor spirit in Queer's purple flowers, magic hour sunsets, and an early sex scene taking place in a neon-lit hotel room that has more of the uncanny aura of Suspiria than Guadagnino's own excellent 2018 Suspiria remake. The Mexico City Queer creates is willfully ahistorical, was never real, but it makes you wish it was.

For all this, however, my first viewing was a mixture of enjoyment and impatience. The languidly paced plot is frequently interrupted by Lee's visions and dreams, which ramp up at an uneven pace. Though David Cronenberg's adaptation of Burroughs' Naked Lunch[1] is the obvious comparison, it also for better or worse recalls Terry Gilliams' transmogrification of Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which eventually has the wearying vibe of a stoner excitedly telling you about this crazy dream he had, man.

It wasn't until the movie's ending, a hallucinatory vision that overtly references the death of Burroughs' wife that I got a sense of what it was doing: not just adapting a book but adapting its author's life which so informed it. Ordinarily I don't have much patience for an adaptation that feels incomplete without knowing the source material, but then Queer, and queerness, isn't ordinary, is it?

II. "I'm not queer, I'm disembodied."

The book is a title out of time. Written in 1952 while Burroughs was trying to publish his debut Junkie, a loose fictionalization of his agonized pursuit of American student Adelbert Lewis Marker the year before, it ended up having entire chapters cut and pasted into the latter book to bring it up to proper novelistic length. Its forthright--not to say proud--homosexuality made it likely unpublishable, and so the manuscript remained the stuff of literary legend until 1986. Publishing it meant piecing the manuscript back together from disparate copies, as well as fresh composition of a new, first-person, epilogue. The net effect is to make Queer a patchwork text, a cut-up like those for which Burroughs had become famous between the time of its writing and publication.

Luca Guadagnino's Queer is perhaps inevitably a more holistic object. It is a faithful adaptation, albeit one that trades the source's piecemeal nature for unity and artful arrangement. The anachronistic music simulates the disjunction of the cut-up method, but the choice of scoring Lee's solitary walk and first glimpse of Allerton to Nirvana's "Come As You Are" is as much a nod to Burroughs' connection to Kurt Cobain as it is a reflection of Lee's mood--and a canny, reportedly unconscious, foreshadowing of Allerton's fate.

The subtlest but perhaps most consequential change is a softening in Lee himself. Burroughs scholar Oliver Harris notes in his introduction to the 2009 edition of Queer that Lee is a particularly ugly American, who often sees the world in martial and imperial terms and is prone to offhand caustic joking-not-joking asides about lower-status groups, with particularly backhanded appraisal of his fellow queers. He observes a group of "Mexican fags" as having "the stylized gestures of a temple dancer," "a depraved animal grace at once beautiful and repulsive." In his first conversation with Allerton about his "proclivities," Lee relates his disgust on discovering he was a homosexual, only to be guided by an old queen, Bobo, who taught him "to conquer prejudice and ignorance and hate with knowledge and sincerity and love." Bobo gets a cruel punchline, a "sticky end," his guts blown out the back of a car.[2]

Harris situates this in the context of Burroughs' own discomfort with the gay community of his time, whose turn-the-other-cheek liberalism he despised. This would endure even as the scene turned militant: Burroughs and the post-Stonewall gay rights movement, representing individual and collective action, regarded each other with mutual suspicion, and it is only recently that gays have taken steps to reclaim him.[3]

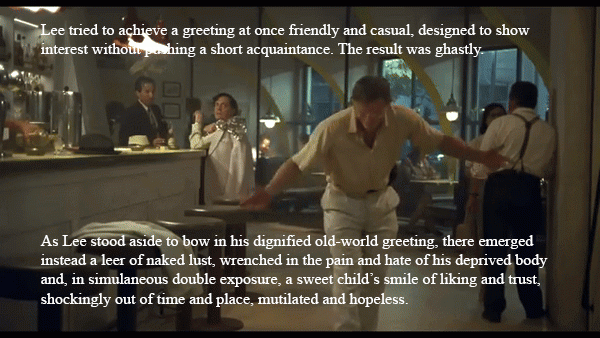

For his part Daniel Craig approaches the role of William Lee with no ego, no bids for sympathy, and unafraid of coming off a little pathetic: dissolute, unkempt, loose and open. Midway through there's an unbroken minutes-long shot of him shooting junk by himself in his apartment, after which he spends the next half-hour of the film increasingly sweaty and dope-sick. Craig has only one of the character's numerous "routines" of the book, extemporaneous shaggy dog stories where Lee adopts the voice of some exagerrated character in order to impress a sometimes imagined audience--but he conveys that same sense of desperate showing off.

Performances are made in the edit, and while nothing about Craig's portrayal of Lee has been changed per se, excisions have been made. The original cut of Queer was said to have been 185 minutes long, and while it was speculated that some of the spicier sexual content may have been cut for American distribution, the missing material likely comprises the more abrasive edges of the character. The screenplay contains many additional and extended routines, fantasias, and moments--like Lee stubbing out his cigarette on the crotch of a sculpture of Simon Bolivar or a routine that describes Tibet as "High and cold and full of ugly looking people and llamas and yaks"--that make him less natural an audience surrogate. Likewise the story of Bobo skips his unhappy ending and instead goes straight into the old queen's extortation and Lee's conclusion:

'No one is ever really alone. You are part of everything alive.' The difficulty is to convince someone else he is really part of you.

The effect of the cuts is to make Craig's version of Lee not wholesome by any means, but with fewer points of friction that would alienate the modern viewer. I can't say I miss these aspects--the fewer reminders that the character's author was a southern trust fund baby, the better--but I should like to see a director's cut that makes the audience's push-pull identification with Lee match the complications of Lee's relationship with Allerton. As it is the cuts give the audience a more consistent Lee to hold onto, and greater focus on Bobo's words in particular clarifies the unity between the narrative's two threads: Lee's pursuit of both Yage and Allerton, the former the means by which he attains the latter in the adaptation's other most significant change, the ending.

III. "Think of it: thought control. Take anyone apart and rebuild to your taste."

Queer's haphazard construction is most acutely felt in its original ending. Lee brings Allerton with him to the mouth of the Amazon in search of Yage. They hack their way through the jungle to the thatched hut of a botonist, Dr. Cotter, who is suspicious and has nothing to offer and sends them away. And that's it. The narrative doesn't end so much as it just trails off, and then the 1985 epilogue picks up two years later.

Guadagnino doesn't change this outcome, but instead recontextualizes it with new material. Dr. Cotter, male in the book, is in the movie a woman (Leslie Manville, feral and very funny), a kind of mirror image of Lee: she is paranoid and apt to pointing firearms at him, and her husband is likewise some twenty years her junior. She eventually reveals that the ayahuasca is all around them and boils a concoction of it that the four of them drink. After thinking it's having no effect, Lee and Allerton both puke their hearts out onto the ground, read each other's thoughts, and then physically meld their bodies in and out of each other. It's like Aristophanes' description of soulmates finding each other in The Symposium, two reunited halves of a single, splay-limbed whole, by way of the gross-out climax of Brian Yuzna's Society. Dr. Cotter tells Allerton this is only the beginning, that he must step through the door of perception that they've opened, but he's had enough. The two men depart and Lee loses Allerton in the jungle. As if in acknowledgment of the book's narrative break, Lee is flung through space and time into the Two Years Later epilogue.

Aside from its inherent value as surreal spectacle, the Yage trip escalates and breaks a cycle that Guadagnino has found in the book and finessed. The movie's three-chapter structure divides it based on location: first Mexico City; then Quito and Manta, Equador; and then the Ecuadorian Amazon. Within each of them Lee and Allerton's relationship crosses a new threshold of intimacy that Allerton then recoils from. First a drunken oral exchange, after which Allerton avoids Lee's company, and then penetration, which is followed by a scene where Lee reaches out to Allerton, who instead slugs him for breaking their agreement that he only "be nice" to him twice a week. That Allerton abandons Lee for good after this third, transcendental coupling is in keeping not only with the novel's conclusion but also with who Allerton is as a character, unable to resolve his own contradictory feelings about Lee and his own sexuality.

The epilogue in the book has Lee returning once more to Mexico City, where he learns Allerton was last heard going to South America. He dreams of finding Allerton, not as himself but as one of his routines, the Skip Tracer of the Friendly Finance Corporation calling due. Allerton remains wordless as ever, and the book ends with the Skip Tracer promising he'll see him soon. The epilogue doesn't necessarily resolve anything, but it does tie off the severed relationship like a tourniquet. That it's done by a retreat into the subconscious and Lee's own raconteurism is fitting. It's a good ending. Guadagnino does it better, however, by pulling not just from Burroughs' desperate infatuation with Lewis Marker, but the shooting of his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer.

IV. Ultimas Noticias

The relationship of Burroughs' wife to his second novel pulses with contraction and expansion like a telltale heart. The text is not even oblique about her absence; the unknowing reader would not even think to ask where Lee's spouse is, as he would not even know she exists. Yet it is Burroughs, not Lee, who pressed the subject. In his introduction written for the book for its belated 1985 publication, he declared that "The reason for this reluctance [to read about and reflect on a painful personal history] becomes clearer as I force myself to look: the book is motivated and formed by an event which is never mentioned, in fact is carefully avoided: the accidental shooting death of my wife, Joan, in September 1951." First there was the shot, then the echo in its absence, and then reverberations in Burroughs' memory until it was as deafening as the original.

According to Burroughs' initial statement to the Mexico City police, during a gathering with friends (including Lewis Marker) he and Vollmer attempted to show off his 'William Tell routine,' in which she balanced a shot glass on her head and he took aim with his Star .380 automatic and missed.[4] Burroughs in his Queer introduction goes on to write of his sincere and very literal belief that he was possessed by an "Ugly Spirit" that night, and that was what killed Vollmer. "I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death," he says, reasoning that he would resist the Ugly Spirit for the rest of his days, in writing.

Setting aside the self-serving convenience of this explanation, it is clear that Vollmer's death haunted Burroughs, far more than any Ugly Spirit preceding. After dredging up the memory of it with the publication of Queer and his introduction, the William Tell routine made its way into David Cronenberg's 1992 adaptation of Naked Lunch as Cronenberg felt that history was a critical element of the book itself. "It’s Joan’s death...that first drives him to create his own environment, his own Interzone. And that keeps driving him. So in a sense, that death is occurring over and over again."

In Guadagnino's adaptation, that death which so hangs over the work is manifested in its ending. Lee returns to Mexico City, and after learning of Allerton's whereabouts returns to the hotel where earlier he had a tryst with a local boy, lays on the bed, and dreams. He dreams of finding a scale model of the hotel, peering into it and looking on himself as he walks the hallway and enters. Allerton lays on a bed beneath a pane of glass in an otherwise empty room. He rises, shares a telepathic glance with Lee, places a shot glass atop his head and nods. Lee removes his pistol, aims, fires, enacting the shooting of Joan Vollmer right down to the unbroken shot glass tumbling away.

Lee, distraught, takes Allerton in his arms. Allerton fades away. Lee goes to leave the room, and he fades away too. He is in the hotel room, aged and withered and "looking uncannily like Burroughs at 83, the age of his death," and as he lies down on the bed for a final rest, he is joined in spirit by the younger man.

To take this whole last sequence at face value, especially without familiarity with Burroughs' life, is to believe that Lee never moves on, literally never leaves that hotel, and dies pining after Allerton. This is not necessarily wrong, there's no right way to interpret a fever dream, but it is a rather literal way of reading a movie that has insisted on its subjectivity from its opening credits, which end on a shot of the first page of the original manuscript for Queer. The choice to end the movie by symbolically transposing Joan Vollmer's death onto Allerton closes that loop, like a snake devouring its tale, by making literal the odd co-mingling Burroughs had engaged in with the book. Though he said in 1985 that the book was about Vollmer, at the time of its writing he baldly declared he had written it for Marker. "The self-loathing in Burroughs' self-portrait is haunted by the memory of death as well as the masochism of desire," Oliver Harris wrote of the twinned influence, and it's likely he said something similar when advising Luca Guadagnino and Justin Kuritzkes on their adaptation. Seventy-three years since Vollmer's shooting and Marker's departure, thirty-nine since the Skip Tracer hummed "Johnny's So Long at the Fair" and promised Eugene Allerton to settle his account, death and desire come together once more in those final moments.

Beyond biographical considerations, the ambiguous ending works an expression of an emotional truth, the feeling of longing and loss not unlike that explored in the equally divisive ending of All of Us Strangers the year before. Guadagnino has dealt with such emotions in his work previously, the ending of Call Me By Your Name in particular marinating in gay heartbreak. Befitting its more middle-aged perspective, however, Queer's ending is not so heart-searing as that of an adolescent with the rest of his life in front of him. Instead it bears a deeper ache, of moments lost in time like hourglass sand that's slipped through one's fingers. Hardly queer, that, no matter the when or where.

Whose title it owes to Queer, specifically Alan Ginsberg mistaking an excerpt to read "naked lust" ↩︎

This passage ended up being repurposed in Naked Lunch, as an aside about a Professor Fingerbottom in Vienna, as part of a longer routine about a society of paranoiacs who grow clones of themselves. ↩︎

Burroughs was outraged by a publisher's suggestion that Queer be retitled Fag, a title which would instead go full and pluralized, ironically, to budding gay activist Larry Kramer's lacerating 1978 novel about hedonistic gay ennui in pre-AIDS Fire Island. ↩︎

His lawyer Bernabe Jurado would later have him change his story say that he dropped the gun and it discharged, only to change it again to say that he was showing it to his friends and it went off in his hand. A character in his own right, Jurado would eventually shoot a man and skip town, prompting Burroughs to do the same. ↩︎

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion