Separating the National Culture From the Nation

Greetings, friends. In this installment my Oscars catch-up continues with the bewilderingly nominated Emilia Pérez and another Best Foreign Picture nominee, The Seed of the Sacred Fig. With that are some more newsy items on Kendrick Lamar's halftime performance and the now uncertain fate of the Kennedy Center made this one something of an assessment of what the relationship between art, commerce, and the state. Not that that is particularly relevant at this moment in time!

Ask Not What Your Country Can Do For You

Ask What You Can Do To Your Country

Donald Trump's self-installment as chairman of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and purging of its board of directors is not the most dangerous development since his inauguration less than a month ago. It's not even the most harmful to the arts. But it is perhaps the most tacky, which when it comes to the health of a national culture is about as bad as it gets.

The Kennedy Center's role in American arts has always been aspirational. New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago have always been the engines of the country's high and low cultures, and even within Washington, DC its Georgetown-Foggy Bottom location put it at a remove from the city's surprisingly vibrant theatre scene. But at the same time, that separation and elevation was a signal from the American government that art and artists mattered and should be celebrated and supported and showcased. And it did well by them. It's been the home for decades of the American College Theater Festival, it hosted meetings of the DC Metro Area chapter of the Dramatists Guild, and the free programming on the Millennium Stage made it a stop for what at this point must be tens of thousands of performers. Although its vaulting ceilings and marble facade were sometimes an awkward fit for the more populist players who milled about its stages, it did real work in supporting the ground-level artists that form the base of America's far-flung culture.

And then there was the big stuff. My first job when I lived in Washington, DC was ushering part-time at the Kennedy Center. I worked in the Theater Lab, which contrary to its name has been the home of Shear Madness, an interactive crowd-pleaser mystery comedy, since 1987. I didn't care for the show, though I appreciated how much its very talented cast could enliven the material. I was allowed to pick up shifts in the other theaters, and periodically staff would get offers of free or discounted tickets to shows. In this way, while still living on a lunch money budget, I got to feast. The Bernadette Peters-starring revival of Follies. A collection of Samuel Beckett shorts directed by Peter Brook. Cate Blanchett and Hugo Weaving in Uncle Vanya. These are still some the best shows I've ever seen, and the sheer size of the place allowed it to host all of them and so much more.

And now this will all be subect to the capricious whims of a man who previously had a staffer whose sole job was to put on his favorite Andrew Lloyd Weber standards to calm him down when he was in a rage. This is clearly a power move, an iconoclastic defacing of a temple of the uptown Manhattan crowd he was trying to impress when he was still a vulgarian real estate developer from Queens. We would be lucky if the worst thing to happen to this country in the next four-plus years was an endless gilded season of spectacular spectaculars with set design by Melania. As it is, the cultural coup is apt to turn the Kennedy Center into a monument to bad taste.

Speaking of which...

"Let’s acknowledge that the Oscars are bullshit and we hate them. But they are important commercially… I’ve learned to never underestimate the academy’s bad taste. Crash as best picture? What the fuck."

Snarkocorrido

Emilia Pérez

(dir. Jacques Audiard, 2024)

No movie on the 2024 Oscar slate represents the state of that bastion of Hollywood respectability like Emilia Pérez. The film came out of nowhere—that is to say, Netflix—to win Best Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globes and garner 13 Academy Award nominations, the most an international film has ever been nominated. It faced ferocious criticism from Mexican and transgender critics along the way, however, for what they considered poor representation and stereotyping. Which isn't new. Academy favorites may have gotten stranger in recent years, with Best Picture winners that include a 50s sci-fi throwback romance between a deaf-mute woman and a fish person and a multiverse action-comedy that uses a butt plug as a plot device, but the guiding ethos of feel-good white liberalism that elevated Crash and Green Book still holds brittle sway.

I'll weigh in on all that shortly, but first I must make clear that the Academy committed a category error. The title character is not the lead: that would be Rita (Zoe Saldana), a Mexico City defense attorney who is especially good at keeping her corrupt political clients out of jail. She is hired by drug lord Juan "Manitas" Del Monte (Karla Sofía Gascón), who hires her to facilitate a surgical male-to-female transition and then relocate his wife (Selena Gomez) and kids to Switzerland so he can fake his death and start a new life with a new identity.

This occupies the first half of the movie, and Saldana is in nearly every scene. She's good, too, arguably the best part. She brings her experience as a dancer and a motion-captured action star to the two biggest musical numbers, and zeroes in on the ambivalence of a character serving a rotten system. Gascón is mostly relegated to the background during this segment. Wearing facial prosthetics and speaking in a hoarse rasp, she appears enough to set up the relationship with Manitas' family, but it is through Rita's eyes that we go through the first hour or so.

I didn't much care for all this, though I could understand why it elicits strong reactions. In its favor are Saldana and "La Vaginoplastia," an absurd musical number about gender reassignment surgery that will be the movie's viral legacy; the score in general sounds good, though the songs themselves are not especially memorable and are sustained mainly by their choreography. Demerits include the cinematography's ugly 'Third World' color grading and the script's sometimes childishly simplistic dialogue. The cartel gangster plot elements here are not really any worse than something like Sicario, and it does make a moving case for transitioning in order to be one's honest self.

So far, so bland, but then Señora Pérez makes her entrance and the movie reveals its gaudy, sequinned heart. Emilia is a new person with a new life, but she cannot help but try to redeem herself by repairing the damage she wrought as her old self. A standard theme that, one that with the transgender framework would perhaps always be heavy-handed but not inherently bad. That comes from the way in which she goes about it: reintroducing herself to her family as a long lost aunt to reconcile with her 'widow,' and using her money and old underworld connections to locate the missing bodies of cartel victims and give their families closure—without disclosing her old identity and culpability as a drug kingpin.

Of the two subplots, the transgender storyline fares better. I can't speak to what it does or does not get right about transitioning, though I have seen queer critics attack for being sensationalist trash, and praise it for the same reason. Treating gender transition as a repudiation of your 'old' life, to the point of faking your death, is a rather literary conceit, very French, the metaphorical deadnaming made literal; and Mrs. Doubtfire is a doubtful model of trans liberation and familial reconciliation. But this narrative does progress and escalate and resolve. It at least gestures toward the idea that one cannot just leave their old self behind, whereas the cartel storyline enthusiastically declares, "¡Si, se puede!"

Words fail to convey just how thoroughly misconceived this subplot is. The idea is that this is Emilia's atonement, but who grants that? Her? The victims? God? Honoring the victims means both apologizing and allowing them to choose whether to accept the apology. If Emilia never has to answer to the people whose lives she at least indirectly helped tear apart, then her redemption is just vanity. Rita, who spends much of the second half of the movie in a support role, complained at the beginning that she was laundering criminals' money, and she's really only changed in that she is now laundering their guilt. Keeping Emilia's secret is not wholly indefensible, it does ensure the bodies are returned to the families, but the movie is oblivious to there being any tension to the scenario. It's morally grotesque and bad storytelling besides.

Heightening the contradictions and forcing confrontations is the stuff of good drama, and there is no better example than in Emilia Pérez's Oscars campaign. In a twist worthy of the telenovelas that the movie tries to emulate, some old tweets by Gascón were unearthed, where she expressed ferocious bigotry toward Muslims, Blacks, and Catalanians. Gascón apologized profusely, but no one was satisfied and Netflix dropped her from the film's press tour and marketing materials. The movie's chances for Oscar gold have more or less evaporated, its fall as quick as its rise. I could not un-hear this discursive din, but in the interest of fairness I did as best I could to set it aside. In doing so I could see the movie with clear eyes for the tasteless boondoggle that it is. We all have to do our part to combat prejudice.

The Only Winning Move Is Not To Play

If the Kennedy Center and the Oscars represent America's reach toward high, Empyrean culture, then the Super Bowl is the earth to which it falls, and the commercial frenzy surrounding it the infernal downward slope. The climax of the modern-day gladiator match that is American football season, the Super Bowl is the most-watched annual live event in the country, its television ad time the most expensive, and its commercials the most hallucinatorily opulent, the anti-Dada (Adad?) vanguard of capitalist art. At its center is the half-time show, where the winners of the music industry's Darwinian meritocracy perform for the audience that put them at the top. The tension between democratic ideals and wealthy patronage is refreshingly absent here; this is what the people watch. Of course President Trump would want to attend.

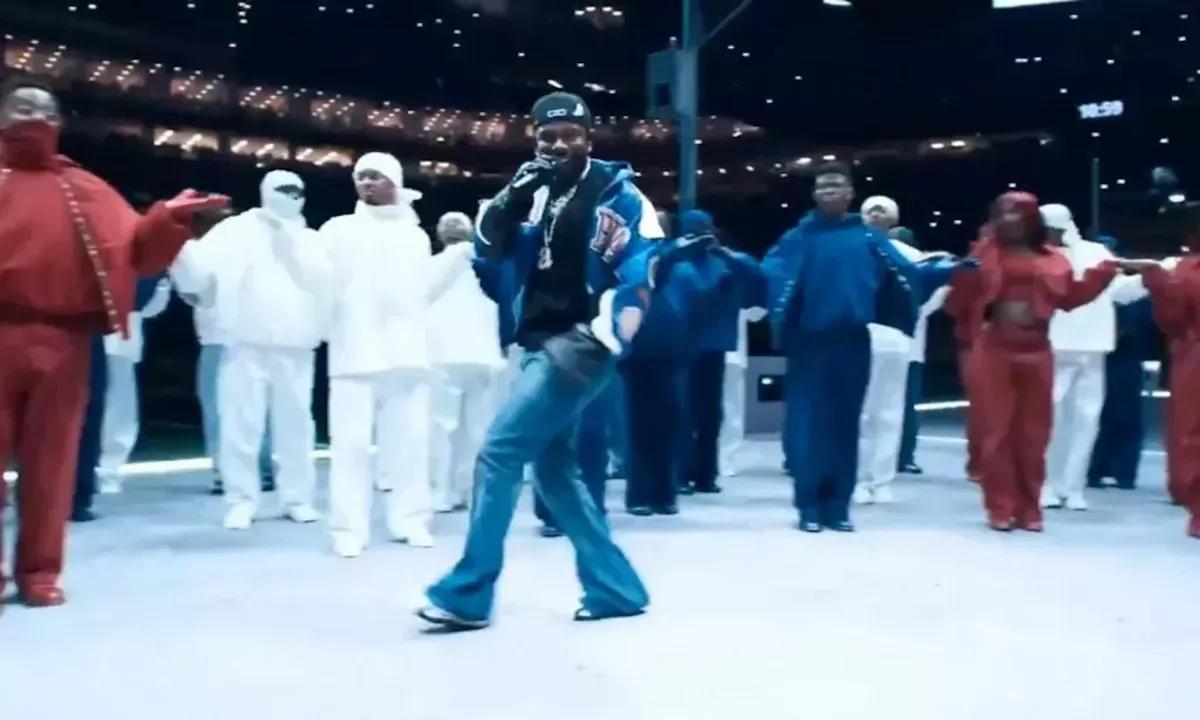

The half-time show had booked rapper Kendrick Lamar, however, an outspoken advocate of the Black Lives Matter movement that Trump had previously tear-gassed during the 2020 George Floyd protests. Some kind of capital-S Statement seemed likely, desirable, inevitable. Might Kendrick use his turf-friendly platform to pull a Sinead O'Connor? He's walked the minefield intersection of activism and the music industry, and as his feud with Grammy-winning shower singer Drake shows, he is an evil genius at manipulating public attention.[1] So instead he addressed the Republican elephant in the room obliquely, by not addressing it. His show was less a concert performance than performance art, with imagery and references pulling from Americana, video games, and Black peoples' contested place within the culture—and also an endzone spike over Drake's tombstone, the subject of most immediate reactions.

The performance did not make a material difference, but short of stopping the show and the game entirely, that was never going to happen. It would be too much to expect meaningful change to come a half-time show, but that doesn't mean it could lack meaning. Whatever its economic importance, the Super Bowl is a cultural institution, and Kendrick Lamar fought in cultural terms, which ultimately meant appealing to the audience. Without any kind of line-in-the-sand statement to seize onto, and the production itself a mini-masterpiece of televised choreography,[2] the Republican Kulturkrieger could only sputter impotently about DEI and reveal the gulf between them and the American people they claim to represent. It's loser shit for a movement whose entire worldview is about winning, a triggering of the triggerers, and a morale boost for everyone else. They are, as the song goes, "not like us."

When There Is No Way, A Way Will Be Made

The Seed of the Sacred Fig

(dir. Mohammad Rasoulof, 2024)

Experiencing genuinely subversive art is similar to having an "authentic" experience in another country as a tourist. If the official channels are selling it to you, it's already been co-opted. The wildflower you bought is already wilting. Real culture and subversion exists, but that's all it is doing; it has to be sought out on its own. The film industry in Iran produces any number of officially sanctioned domestic commercial works—these too are culture, though of mostly academic interest to anyone who doesn't live there—but more than nearly any other nation it is most famous internationally for its art house filmmakers. Receiving very little if any support from the country's theocratic government, they often skirt the bounds of censorship—the real kind, not the 'being mean to you on the internet' kind—to the point many of whom are political dissidents, forbidden to make movies.

Mohammad Rasalouf has trod an especially perilous path. Having previously been arrested and banned from international travel and making movies, he was in the process of directing his latest film, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, when he learned he had been sentenced to eight years in prison and flogging for "collusion with the intention of committing a crime against the country’s security." The appeal process took just long enough that he could complete filming, and when he learned that his appeal had been denied he fled the country on foot with no electronics, eventually making his way to Germany to complete the film and bring it to Cannes. When it came to the Oscars, it was Germany's submission, not Iran's. Rasalouf does not know when or if he will return to his home country.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is an appropriate movie for the moment, by design. Set during the protest movement that erupted in late 2022 in response to the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini, the plot concerns the family of Iman (Missagh Zareh), a career attorney promoted to the position of investigative judge for the Islamic Revolutionary Court. So widely despised are the judges that they could be killed, and so he and his wife Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) do not tell even their daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sama (Setareh Maleki) the nature of his promotion and why they suddenly have to keep their friends at arm's length.

The plot unfolds along parallel lanes, the government father and the rebellious daughters, with Najmeh as the conduit between them. She is loyal to both her husband and her children, and so she embodies the movie's tension—and the nation's—as the one trying to prevent the situation from spiraling out. Hard enough when eldest Rezvan brings home a friend shot in the eye by police at a demonstration, and harder still when Iman's paranoia begins to grow.

The setup alone is tight thriller material, elevated by the movie's proximity to real-world events. The social media videos of violent police crackdowns on protesters that Rezvan and Sama watch on their phone are actual videos captured during the demonstrations.[3] The real world influences the narrative, and the reverse as true as well; the IRC that Iman works for also sentenced Rasoulof to prison time, in part because of his understanding but extremely unflattering portrait of someone who serves such a system. Iman is early on genuinely conflicted about his job, because the overflow in arrests means he is functionally rubber-stamping death sentences for people whose cases he has barely had time to look at. But this is a procedural issue, one he makes peace with it soon enough; ideologically he is sympatico with the regime and its brutal judgment of dissenters from its orthodoxy.

The consequences of this take the movie out of realistic thriller territory into something like the The Shining. This is not the more even-handed approach of the movie's first half, yet it works, both as an escalation in tension, and for how it effectively telescopes the stakes of the story from filicide at the political level down to the personal. Iman ends up not at all who we thought he was, but extreme circumstances have a way of revealing one's true character.

Apart from the context in which it was made, and in which I saw it, The Seed of the Sacred Fig stands well enough on its own. It looks excellent, not at all like a low-key guerilla operation that was only able to shoot a few days at a time for three months. It is more bracing and alive than most movies with a generous budget that are not evading arrest. A nation and its government should support its artists, but even when they don't, even when they actively impede and suppress them, they will continue to create. The artists will find ways to thrive without their tyrant rulers, and they will show the people, and then the tyrants will have no one left.

Going in I only knew the fact of Kendrick's beef with Drake, and none of the fine details. Catching up on that feud has been a balm in this cursed week, so for those still in need of guidance, Josh Johnson's explainer is a very funny and relatively concise summary. For the deep lore and its deeper significance for rap, pop music, and the culture, F.D Signifier's 3.5 hour dissertation is a great listen. It is a saga of creative conflict and jealousy on par with *Amadeus*, if Salieri and Mozart's roles were reversed.

↩︎The entire performance and how it was choreographed with the camera in mind should be considered proof-of-concept for other live performances, dramatic and and musical alike, designed for audiences at home as much as in the venue.

↩︎Last year had several movies that used real-world video to blur the boundaries between news and narrative. Civil War included dubiously sourced footage of the George Floyd protests, Monkey Man spotlighted anti-Muslim riots in India, I'm Still Here had archival footage of dictatorship-era Brazil, and even the little indie We Shall Not Be Moved used footage of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre to give context to its plot. This isn't a revolutionary technique, and it may well be that a number of movies do this each year. It is striking in the context of so many mainstream American films that take place in an eternal present, absent of any kind of politics or even a post-Covid signifier.

↩︎

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion