Sex and Death in the Second City

Greetings, friends! This entry's a fun one, a short trip to Chicago I did last week. There I caught some movies I would have otherwise missed out on in theaters, The Visitor and The Shrouds, for reasons that will soon become obvious. The former is available on Video on Demand due to its extremely limited theatrical exhibition, though I beg you learn what you're getting into before you watch it. If you are put off by the trailer, the movie is absolutely not for you. I'm cooler on the latter film, but it's still invaluable as an unmistakably personal film in a film industry where that is becoming all the more rare.

Sexual Diversity in Chicago

There's a gay bar joke that goes something like this:

Q: Why doesn't Chicago have The Eagle?

A: Chicago is The Eagle.

I have lived in cities with large gay populations by raw numbers (New York) and per capita (Washington, DC), but none have thrummed with the queer vibrancy of uptown Chicago. Boystown gets all the attention, but go anywhere further up the CTA Red Line and it won't be long before you come across crunchy lesbians, sloppy bears, and genderfluid gamines. Chicago as a whole has a more working-class vibe than the more stratified American cultural and political centers, and so without the need to keep up appearances, the freak energy (complimentary) flows a little more freely.

With New York's sheer size and critical mass of queers and tastemakers (but I repeat myself), it's unsurprising that it got a New York Magazine write-up and the American premiere of Bruce LaBruce's hardcore propornganda film The Visitor. But the fact that the movie came to Facets, a Chicago film institution but one more off the beaten path than the Gene Siskel Center or even the Music Box, bespeaks an irrascible queer spirit. It was reason enough for me to plan a visit back to the city, a decision rewarded by the experience itself.

The showing was preceded by some appropriate programming. First up was camp icon John Waters' iconic 1981 smoking PSA.

Next was a short by Program Operations Manager Nick Edelberg which takes audio stripped from a decades-old evangelical Christian anti-porn program, and juxtaposes it with equally old stag film footage processed into a hallucinatory mirrored and doubled kaleidoscopic image. I have my quibbles with the latter, as the visuals are so abstracted that the contrast between sound and image is dulled and the imagery becomes diffuse enough to project on the wall at a hip party and not to pay attention. All the same, it was terrific mood-setting for the group of generations-spanning mostly queer, mostly male sinnerphiles in attendance.

Topping it off afterward was a pre-taped Zoom interview with LaBruce that covered all aspects of the production: its origins as a photo shoot for a film that Doesn't Exist, the different responsibilities for intimacy coordinators on mainstream movies versus porn, the support of an underground arts organization founded by an eccentric Kazakh billionnaire. Facets is hoping to put together a Bruce LaBruce retrospective at some point, and I can't think of a better city for LaBruce's brand of playful, prurient polemic.

Dialectical Smut-erialism

The Visitor

(dir. Bruce LaBruce, 2024)

There are many movies where, upon seeing it, one can easily think of another it would pair well with as a double feature. Rarer is the film that one thinks of a movie with which it would pair poorly, because the other would suffer for the comparison. The Visitor is one of those rare speciMen, as one of my first thoughts after watching it was how thoroughly it eats (out) Saltburn's lunch. Both are movies about a lower-class male outsider being welcomed among their betters and sexually destroying them from within. But where Emerald Fennell's notionally queer Eat The Rich geek show wants you to tell it how naughty and rebellious it is with its sexless slurping usurpation, Bruce LaBruce just goes there, with assaultive cherry-popping agitprop whose commitment to the bit is the straightest thing about it.

Remaking Pier Paolo Passolini's Teorema, the arthouse porno parable tells of a Visitor (Bishop Black) who washes ashore in London and proceeds to ingratiate himself within the household of a posh family, consisting of a Maid (Luca Federici), Mother (Amy Kingsmill), Father (Macklin Kowal), Daughter (Ray Filar), and Son (Kurtis Lincoln). The Visitor debauches them with sexual revolutionary fervor, then leaves them born anew to spread the word and their legs to the rest of the world. Where Passolini's film and companion book were a parable of the Italian bourgeoisie and its mores being exploded by their encounter with the divine, LaBruce here takes aim at far right xenophobia, the scenario playing out like a parody of nationalist nightmares of foreign impurity.

To that end the whole thing is shot through with a style best summarized as militant camp fantasia. The emergence of the Visitor is overlaid with a Narrator (Adrian Bracken) bellowing right-wing propaganda, while the sequences of corruptive copulation are regularly superimposed with horned up political slogans ("Vote For Sex Change", "Keep Calm and Fuck On," "The Complicity of the Dom-Proletariat and God"). Except for a series of climactic confessions, dialogue is minimal. Scenes unfold like a performance art slapstick silent movie sketch, operating more on dream logic than any kind of natural narrative. The mood is guided by Hannah Holland's pulsing techno woven score, woven with a whirring theremin that pushes the idea of an alien invasion into 50s sci-fi territory. Least pornographic of all, the movie is shot with an eye for composition, edited for impact, and color graded with strobing chromatic filters, all of which give it the feel of a communist dance party.

Edelberg, in opening the presentation, said that Bruce LaBruce is always grateful to the theaters that screen his movies because "they're not for everyone, nor should they be," which is about right. Decades of queer activism yielded important legal victories, but it gave way to a corporate rainbow capitalism in the 2010s that sat uneasily with the continued vulnerability of young and trans populations. Its insincerity has been exposed by how easily companies like Disney and Target have folded to appeal to and appease the reactionaries who considered even sexless Ken doll queers were a threat. The Visitor shows them what a real threat actually looks like: a "pansexual revolutionary" espousing solidarity, in the sheets and the streets.

The timing of my trip worked out such that I was also in Chicago for the opening of David Cronenberg's latest, The Shrouds. It's all but certain not to make it out my way; I had to schlep out to Lynchburg, Virginia of all places to see his last picture, Crimes of the Future, and on the drive there I saw a man carrying a large metal cross on his back across the highway, which is more perverse than anything in the movie. Which is to say I had to catch The Shrouds at the Music Box, though alas the screening with a director Q&A afterward was already sold out (Freak City, babyyyyy). Cronenberg has been one of cinema's foremost pioneers of alternate sexualities, and so I was expecting this new movie to be complementary to The Visitor, yet it is more of a counterpoint. If that movie and its maker are about sex as a fact of life and therefore politics, The Shrouds is a rumination on death as an even greater biological reality.

Marriage à la Mort

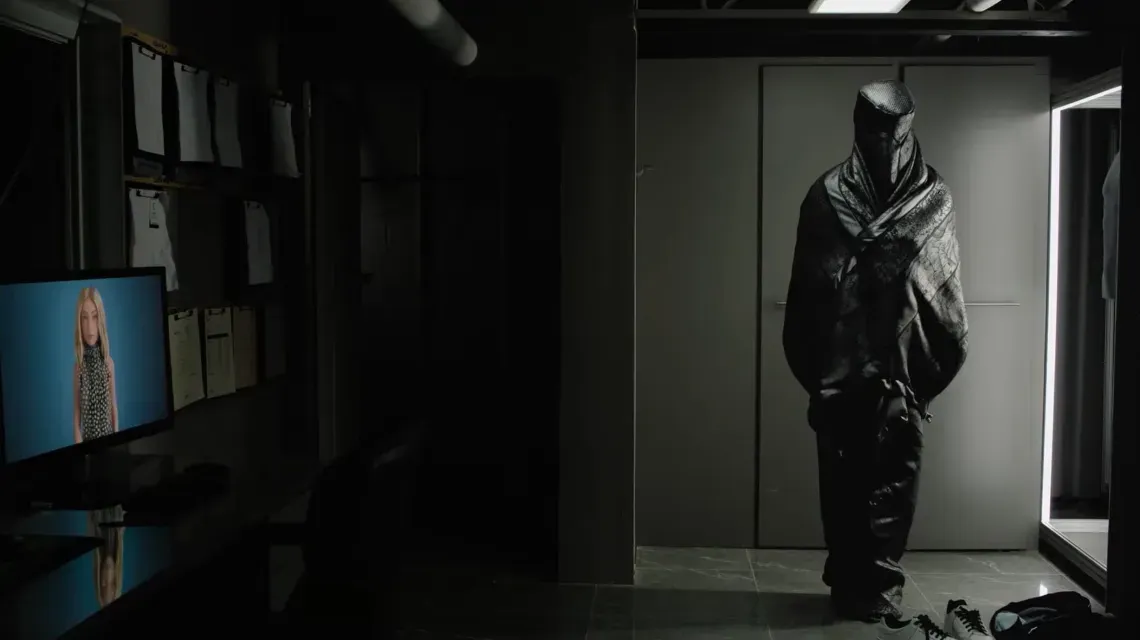

The Shrouds

(dir. David Cronenberg, 2025)

Bodies and their transformations are a career-defining interest for David Cronenberg. The body's final transformation, death, is the subject of his latest feature, The Shrouds, and a natural for the director, now in his 80s and facing his own mortality. Its origins lay in the death of Cronenberg's wife of 46 years, Carolyn Zeifman in 2017, and his own difficulty processing it. The inability to let go on a nearly physical level is the core from which all of the movie's best parts derive. Alas but there are not more of them.

The film's title refers to the invention of its lead, Karsh, played by Vincent Cassell and a dead ringer for Cronenberg himself. Inconsolable after the death of his wife Becca (Diane Kruger) four years ago, Karsh founded GraveTech, whose Shrouds envelope the dead to create a real-time image of their body as it decays, viewable both on the tombstone and in an app. Karsh is haunted by his wife in other ways: memories of her physical deterioration by leukemia in his dreams; the ambiguous relationship he has with her identical twin sister Terry (Kruger again), who, he tells with little self-consciousness, "has Becca's body;" a cartoon AI assistant avatar named Hunny (Kruger once more) designed by Terry's ex-husband Maury (Guy Pierce). One night the GraveTech cemetery is desecrated by unknown vandals, and Karsh's subsequent investigation leads him down a rabbit hole involving strange growths on Becca's remains and cyber-espionage that may involve the Russian and Chinese governments.

The contents of that last sentence are only tangentially related to the rest of the paragraph, but they take up an inordinate amount of runtime. Moreover they involve tertiary characters who appear only sporadically, and the details of their development are talked about at such length that it becomes actively difficult to keep track of it all. Its tech and political signifiers, including Karsh driving a Tesla, are insistently specific to 2025, which due to some truly unfortunate timing already feel dated. The complications don't end up amounting to all that much, and the movie's ending is a stopping point rather than a resolution. It feels like vestigial material from when the movie was going to be a Netflix series, and it doesn't have the surrealistic mood to make the red herrings and loose plot threads a part of the experience like the other former-TV-project-turned-feature-by-a-weird-director-named-David.

Or does it? While the movie feels needlessly plotty, most of the characters are oddly subdued, Karsh most of all. They speak in hushed tones with minimal inflection. This lends it some dry humor, but it drains everything of urgency, talking around its morbid subject rather than about it. The movie is as clinically depressed as its lead, and possibly its author, with Howard Shore's droning score and a low-key lighting scheme serving as audiovisual anesthesia. (To paraphrase David Foster Wallace, think about the literal meaning of that word.) This isn't an inherently bad approach, but it misses the mark when its apathy is applied to material that is of at best secondary interest.

The moments the movie feels most alive are, fitting Cronenberg, its most visceral. A scene where Karsh strips down and drapes himself in a Shroud, with his computer building a visual representation of his naked body beneath it, section by section, has an air of ritual and contemplation in its interface of flesh and tech. Though the dream sequences with Becca feel unbalanced by Kruger's nudity being constantly frontal while Cassell's is tastefully obscured, they also also deal the most immediately with the terror of one's own body betraying them. A late scene has Karsh and Terry at last embracing the psychosocial dynamics of their relationship, but its only real impact is felt on one of the movie's many subplots. These scenes so vividly explore a person's relationship with their own failing body and their partner's, it's frustrating for the movie to return to its under-baked mystery.

It's all the more vexing because Cronenberg grappled with the subject of the death of the body not so long ago. In 2021 he and his daughter Caitlin released a short film, "The Death of David Cronenberg," depicting the man as he faces his own death, literally, as represented by an uncannily accurate latex model of himself as if deceased. Though marred by its otherwise low production valus and the complete absence of sound editing, it is bracingly, strangely moving, despite only being 56 seconds long.

The creation of this short is the only acceptable justification for NFTs.

In the moment of watching The Shrouds it feels like the subject of his wife's death defeated David Cronenberg, that the pain was still too raw to address head-on. The more I sit with it, though, the more I wonder if its dissatisfying evasiveness is the point. Karsh is after all surrounding himself with relics and reminders of a person who no longer exists, and distracting himself with all of the busywork they entail. His Shrouds, rather than cover and protect the dead, expose them to the living. And when he at last moves on there is no closure, only continuity. Life goes on, though some do not.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion