Snatcher: Tech Voir

Hello friends! The second installment in my Hideo Kojima retrospective is here at last. Snatcher is not the longest game I'll cover by any means, but playing two versions of it did lead to me having a lot more to say. For this I've put together a YouTube playlist that kicks off with the opening track for the Sega CD version, with the rest comprised of, appropriately, Kojima's favorite Vangelis tracks, as laid out in an episode of his Brain Structure podcast.

Also, the first proper episode of Mise en Screen, my movie podcast with Steven Santana, dropped this morning. It's on a whole bunch of podcast services now, so if you haven't already listened to it go do so! After reading this, of course.

I. The Prototype

Snatcher

dir. Hideo Kojima, 1988, 1994

Platforms: MSX, Sega CD

Although it has been a full decade since Hideo Kojima went independent and left the Metal Gear Solid series behind, he and his sensibility are still seen through its lens, and not without reason. Metal Gear was his first game, and after MGS's industry-shaking success he would not direct a full-length non-Metal Gear game again until Death Stranding in 2019. That first game is convenient as a starting point for Kojima's career, but it doesn't tell the whole story of his decade-plus career before MGS. For that we have to look at the games that came after, which passed completely without notice abroad if they were released at all.

Coming off a week-long vacation following the release of Metal Gear, Kojima pitched Konami a new game with the working title of JUNKER. Having felt limited as a designer by having to delegate creative work to programmers, he opted to make it a story-driven adventure game inspired by Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii's 1983 The Portopia Serial Murder Case. To better control the flow of story events he had his programmers build him a basic scripting language and compiler, essentially a set of IF and SWITCH statements. "I was able to manage all the pictures, sounds, animations, commands, flags, and programs by myself," he later recalled. "Now I don't have to bow down to programmers."

As a result the team for Snatcher was small, about half the size of that for a Famicom title, with everybody working multiple roles. Kojima has credits within the Editing, Character Design, Continuity, Debug, Flag, and Command units, the design of the title and Junker logo, and the concept for the newspaper shown in the game's opening. He also wrote the game's lore-heavy manual. Under his supervision every screen underwent significant storyboarding and refinement, down to the lighting sources.

The intensive process and requirements pushed the team to its limits; eighteen months and one Kojima ulcer later and still the game's length had to be drastically scaled back from a proposed six acts to two for its original November 26, 1988 release for the PC-8801, with the MSX2 following December 13. Even truncated, however, the game represents a significant step up in Kojima's ambitions and execution. When expanded it shows how much his authorial voice had arrived fully formed.

II. Replicant

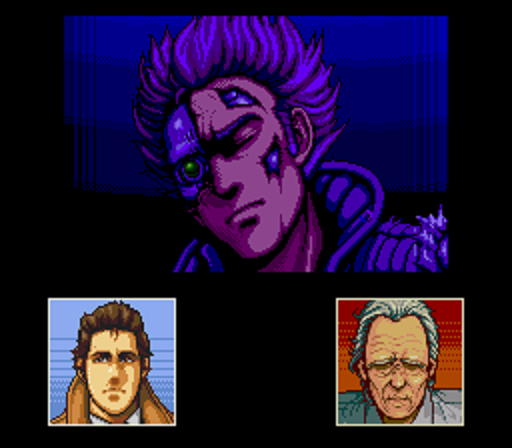

Where Metal Gear's premise and goal could be summarized in a few lines of radio dialogue, Snatcher gets a proper cutscene. To wit: an accident in the Soviet Union's "Chernoton research lab" results in the release of deadly virus Lucifer Alpha, which wipes out half the world's population. Fifty years later another existential threat looms when the citizens of Neo Kobe City begin being replaced by 'bioroid' doppelgangers referred to as Snatchers. Into this steps Gillian Seed, who three years before was found with his wife Jamie in 'the Siberian Neutral Zone.' With no recollection of who they were, the two have recently separated, and Gillian has been hired by JUNKER, Neo Kobe City's agency for investigating and terminating Snatchers.

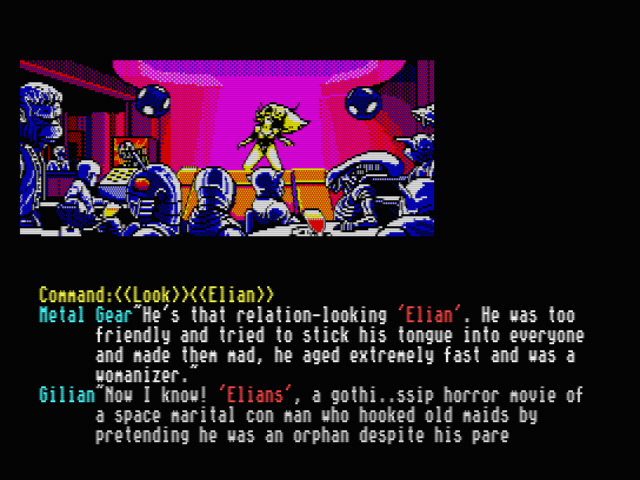

All of this is relayed through expository narrative, but also in expressive mosaic anime-style pixel art, a full opening credits sequence, and music composed to change in time with the visuals. Animation remains limited to a few keyframed elements so that dynamic detailed tableaus can be produced without having to worry about animating all that detail, but not unlike how early anime did the same to stretch out limited production budgets, it punches above its weight. It feels radical for a game that came out in 1988.

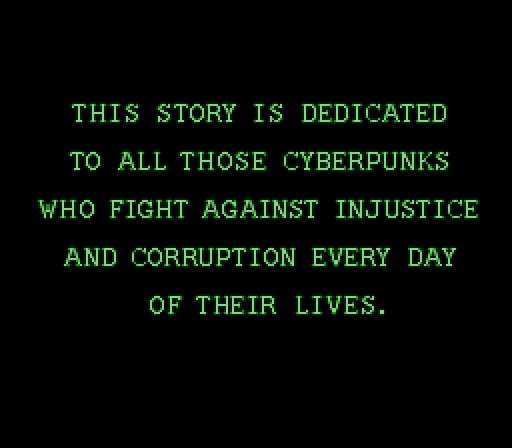

To be sure, much of the game's early effect is lifted from other sci-fi media. The 'bioroid' Snatcher endoskeleton is just The Terminator's T-800, Neo Kobe City homages Akira's Neo Tokyo, and its skyline is ripped straight out of Blade Runner. One of the Snatchers is a dead ringer for Blade Runner's lead Replicant Roy Batty, played by Rutger Hauer, and one character's design is essentially 'Sting in Dune, but anime.' The joke has been made that Snatcher's title, itself a nod to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, could just as easily refer to the pillaged iconography.

Kojima has acknowledged these early homages as a shorthand for his audience to get what he was doing. But even if the game was only that, the fact of Blade Runner's yellow peril vision of a futuristic Los Angeles being appropriated wholesale by a Japanese creator—only six years after the cult film failed to make back its $30 million budget—would still be significant. Ripping off Blade Runner's production design is now standard Hollywood practice, so Kojima was just ahead of the curve (though the similarly-influenced Imitation City released in Japan for the PC-88 just a year before). Fortunately Snatcher is much more than mere ripoff or pastiche, but instead leverages its influences to make something entertainingly new.

III. The New Flesh

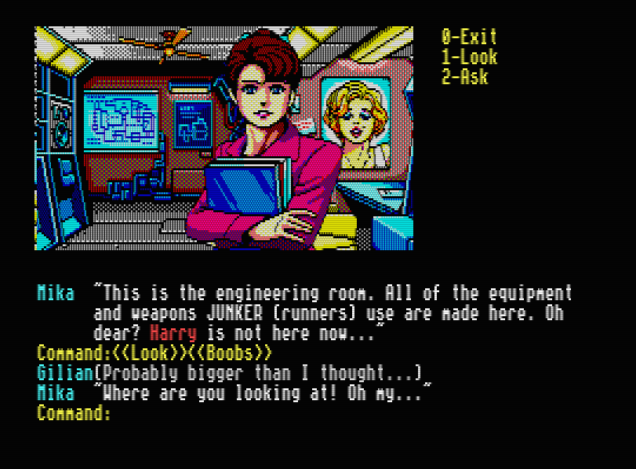

The difference in approach can be seen with a cursory glance at its story, which discards Blade Runner's moody understatement for anime-styled wacky comedy, thrills, and ultraviolence. After meeting the agency's secretary Mika and Chief Cunningham, Gillian meets its engineer Harry, who provides him a sidekick, a small bipedal robot named Metal Gear. A call for backup from JUNKER's other investigator Jean-Jack Gibson leads Gillian and Metal to a derelict warehouse. There they find Gibson decapitated and spot two escaping Snatchers, whose identities they try to deduce with the help of Gibson's daughter Katrina, a Chinese informant who goes by Napoleon, and rogue bounty hunter Randam Hajile.

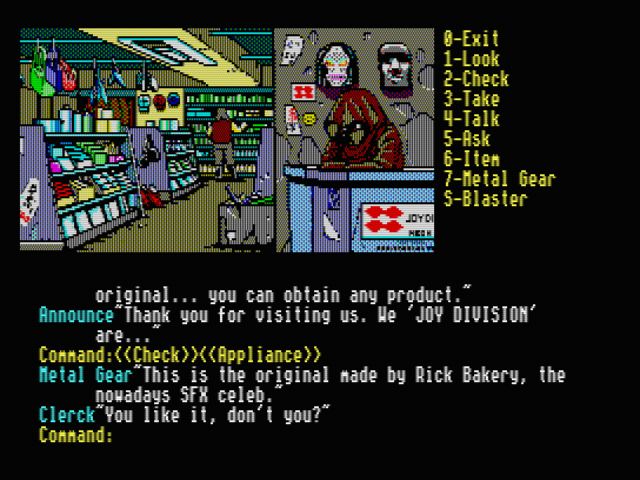

Beyond the plot differences, there is also the adventure game format. Though there are occasional (clunky) shooter segments, the player spends most of their time examining items, objects, and people, all with unique descriptive text that often will say more if selected again. There's even a computer, Gaudi, which contains voluminous details of Neo Kobe City's history, demographics, and culture. There are so many details which help to bring Neo Kobe City to life, which is crucial, since the game is also eager to draw attention to itself as interactive fiction.

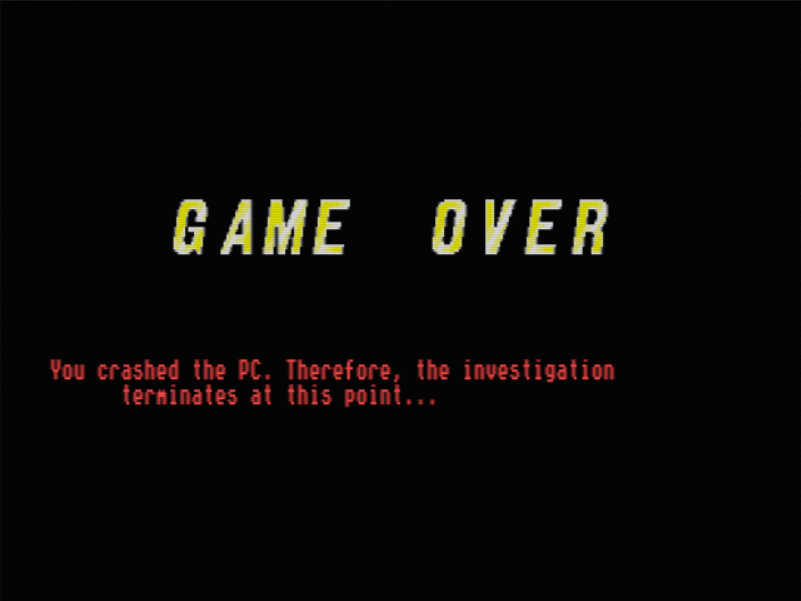

That Snatcher is a game is not so much acknowledged as it is just treated as a fact of life. It begins with the inclusion of Metal Gear, but happens regularly after. Early on "Metal" tells you to turn the volume up in order to hear a ticking bomb, and then chastises you for not turning it back down after the explosion blows out your speakers. Shortly afterward you find a clue from him telling you to "Find home;" when you go to investigate Gibson's home you see he has an ancient MSX2 computer on which he has hidden some key information behind a password: the player's own MSX 'Home' key. The union of the game world and the player's is a Kojima standard, and far from the only one.

Indeed many of Kojima's tropes and pet obsessions show up here for the first time: a sneezing guard, a Moai head, fake jargon and technobabble, dubious biology, a fascination with military equipment. Name-drops and copyright-skirting cameos from Kojima's favorite bands and movies abound. There is even tech that monitors the protagonist's bodily fluids and functions (Death Stranding's poop grenades), with a bathroom that tracks blood pressure, heartbeat, urine, and "manure." Most strikingly, Kojima's eerie prescience is already present; in the original 1988 versions, the Lucifer Alpha outbreak that destroys the Soviet Union occurs in 1991—the year the actual Soviet Union was dissolved.

One of Snatcher's biggest departures from Blade Runner, and arguably its weakest point of comparison, is thematic. The Replicants' existentialism has no analogue, nor the question of Deckard's humanity; essentially there is no cyber in Snatcher's cyberpunk. The Snatchers are straightforwardly villainous, with the game culminating in the revelation that JUNKER itself is compromised and Chief Cunningham is a Snatcher, who sabotages Gillian's vehicle and attacks HQ while he is away. On returning Gillian cradles the mortally wounded Harry in his arms, takes out the "Chief," who attempts to take Mika hostage, and declares that "The real battle starts from [sic] now..." Then the game ends.

It's perfunctory, leaving several plot threads unresolved. It does however provide Snatcher with a final commonality with Blade Runner: a compromised original version whose cult popularity would lead to a subsequent rerelease more true to the creator's original vision—with one caveat.

Interlude: Cybersex Pest

Snatcher took an unusual detour to completion. It was adapted by Konami into an RPG, SD Snatcher, in 1990, with a revamped scenario and an entire new act written by Kojima himself to wrap up the story. It was subsequently ported in 1992 to the PC-Engine Super CD-ROM², whose greater storage capabilities allowed for more detailed pixel art, CD-quality music, voiced dialogue, and the third act, now fully scripted. This version was in turn ported to the Sega CD in 1994 and localized in English. It reviewed well, but U.S. sales were disastrously low, estimated in the 'thousands' range. The later Playstation and Sega Saturn ports never left Japan, making the Sega CD version the only official American release.

This complicates assessing the game in the light of Kojima's authorship. For one thing he was not involved in the American localization led by Jeremy Blaustein, a precedent that would have important ramifications a few years later. The American release also contains several content tweaks, excising potential copyright violations, making certain cultural references more familiar to Americans, and trimming some of the adult elements.

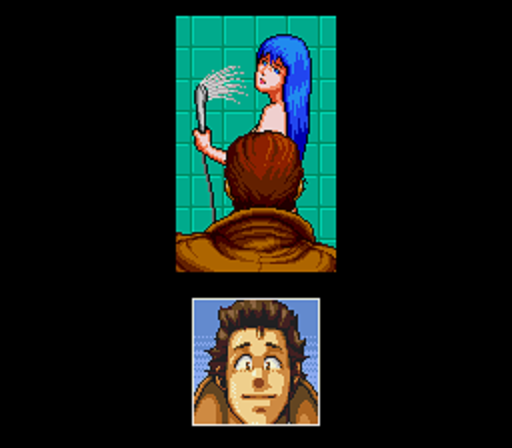

The most significant changes have to do with Gibson's daughter Katrina, the most insistent object of Gillian's wandering eye; a shot of her showering has been obscured, the questions asked to enter her home are slightly less gross (asking about a birthmark instead of her measurements), and she has been aged up from fourteen to eighteen.

Ay, among Kojima's tropes making its first, worst, appearance is his leering camera. Gillian can hit on and strike out with every woman he comes across, and this sex comedy hijinks—which includes walking in on her in the shower—is extended to the youngest such character that would be legally permissible in Japan, where until just last year the national age of consent was thirteen. There's a defense of this that it's all in jest, and Gillian is always framed as a creep and loser when the player makes these choices. The game doesn't gain anything from offering a Ted Nugent option, though, and in fact feels worse for having the same jokey attitude toward sniffing an eighth-grader's panties as it does having a character owning an MSX. Unhappily, this will not be the last time that a purported teenager is sexualized in a Hideo Kojima game, but it's never quite as gross as it is here–but only in Japan.

The American release of Snatcher is not a fully honest presentation of its author's work, but it is far and away the better version for non-Japanese players. It loads instantly and does not require constant disk swapping. The localization is largely excellent, and the 'cartoony' voice acting has a distinctive 90s anime charm. The game is, finally, better for reining in Kojima's worst excesses, making his very real strengths that much easier to appreciate.

IV. Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger

The original version of Snatcher has Kojima's playful design and copious references, but the story, entertaining as it is, feels like a warm-up. The third act, "JUNK," pays it off, exploding the game from sci-fi homage to a decades-spanning geopolitical conspiracy that threatens to tear the bonds of humanity asunder. In other words, it becomes a Hideo Kojima game.

The odd satisfaction of a classic Kojima reveal: utterly batshit yet thematically resonant.

These developments defy summary, but suffice to say they anticipate nearly everything Kojima would make in the ensuing thirty years. Metal Gear Solid would iterate on its protagonist learning his conspiratorial origins, self-sacrificing antihero who is the product of experimentation, and prodigal son wanting revenge on the world. Developments here pivot on the splitting of the world into East and West during the Cold War and its reunification (Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater), and the villain desires to bring about the end of the world by destroying humanity's bonds (Higgs in Death Stranding). There's a name with a jumbled spelling that serves as a dumb accessory to a plot twist (Rat Patrol/Patriots in MGS4, Amelie/Soul Lie in Death Stranding). Even the original abridged release of Snatcher, Kojima's first wholly conceived game for Konami, is a prelude to the unfinished state of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, his last.

It has the odd satisfaction of a classic Kojima reveal, utterly batshit yet thematically resonant. For all that the scheme behind the Snatchers is convoluted nonsense, it's got some teeth: the game's big bad Elijah Madnar chose Neo Kobe City because (like real-life Kobe) it is "a melting pot of various races," allowing him to tap into "the element of suspicion or mistrust, which runs deep in Japanese culture." Some of this comes too late to make its full impact—Elijah is only introduced in this sequence and spends most of it explaining himself—but that narrative overload is in itself exciting, not least because it feels like the young Kojima is surprising himself as much as anyone else.

V. Future Shock

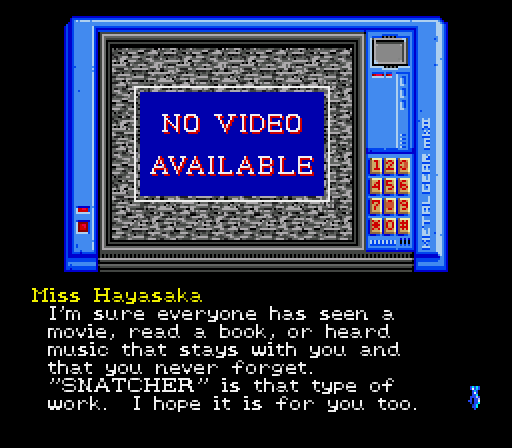

It wasn't until his western breakthrough in 1998 that Hideo Kojima became known for wanting to make games that are meaningful, but he was talking about it as early as 1992. His sentiments made their way into Snatcher itself. In the Sega CD version there's a secret phone call, nominally from Konami head of PR in sales Taeko Hayasaka that is really Kojima's own message to the player:

For the relatively small number of players who played it, the game had its intended impact, which rippled decades into the future. Japanese sci-fi author and Kojima protege Project Itoh's debut novel Genocidal Organ started as "Heavenscape," a loose Snatcher fan fiction. Fallout 3 included an easter egg referencing Gibson's house. Kojima's fellow mad genius game developer Goichi "Suda51" Suda says Snatcher got him into games, and he repaid the favor by collaborating with Kojima on a 2011 radio drama prequel. More recently Argentinian developers LCB Game Studio have cited the game's presentation as an influence on their Pixel Pulps series of adventure games, as has Norco developer Yuts. The game's baffling unavailability on modern systems has bolstered its mystique. Its cult following persists into the present, with the first installment of a 1993 ASCII manga story set in Neo Kobe City archived just last month.

It earns that fervor. Especially in the polished American version, it is cool in its all-encompassing vision, and playing it still feels like glimpsing the future. Even more than the relatively crude Metal Gear, which had been handed to Hideo Kojima as a salvage job, Snatcher represented a statement of purpose from the developer: a love letter to his favorite media (and alarmingly young women) as well as an innovative interactive experience unto itself. Many of its motifs would be reprised in later titles, and during Snatcher's production Kojima came up with the concept for another futuristic adventure game. But while SD Snatcher was being developed he had a chance encounter with a Konami employee which would send him back to Metal Gear, and even more decisively set the stage for his work yet to come.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion