The 'Don't Know Whether to Laugh or Cry' Issue

Greetings! The past couple weeks have been bad in too many ways to count, though the ongoing hijacking of the U.S. government's payment systems by unelected South African apartheid billionnaire Elon Musk is perhaps the most alarming and definitely the most stupid. With that in mind, this week's issue covers some Nazi-adjacent films from yesteryear, and the problems that attend to media depictions of those most heinous of historical actors and their crimes: historical crime thriller The Order; From Darkness to Light, a documentary about the lost Jerry Lewis film The Day the Clown Cried; and Lee Miller biopic Lee. Then to end on a positive note, some words about seeing the 9/11 rerouted flights musical Come From Away the day after the worst American air travel disaster since, well, 9/11.

Die Katze Und Die Maus

The Order

(dir. Justin Kurzel, 2024)

The question of sympathetic evil in art and literature goes at least as far back as Satan in Paradise Lost, but it took on an especial real-world valence in Tony Kaye's 1998 film American History X. A drama about the formation and redemption of a Los Angeles skinhead played by Edward Norton, the film is unsparing in its depictions of neo-Nazi hatred and cruelty, including an unforgettable scene that introduced curb-stomping to mainstream America. Yet these scenes also make their perpetrators look cool and powerful, the way actual neo-Nazis want to be portrayed.

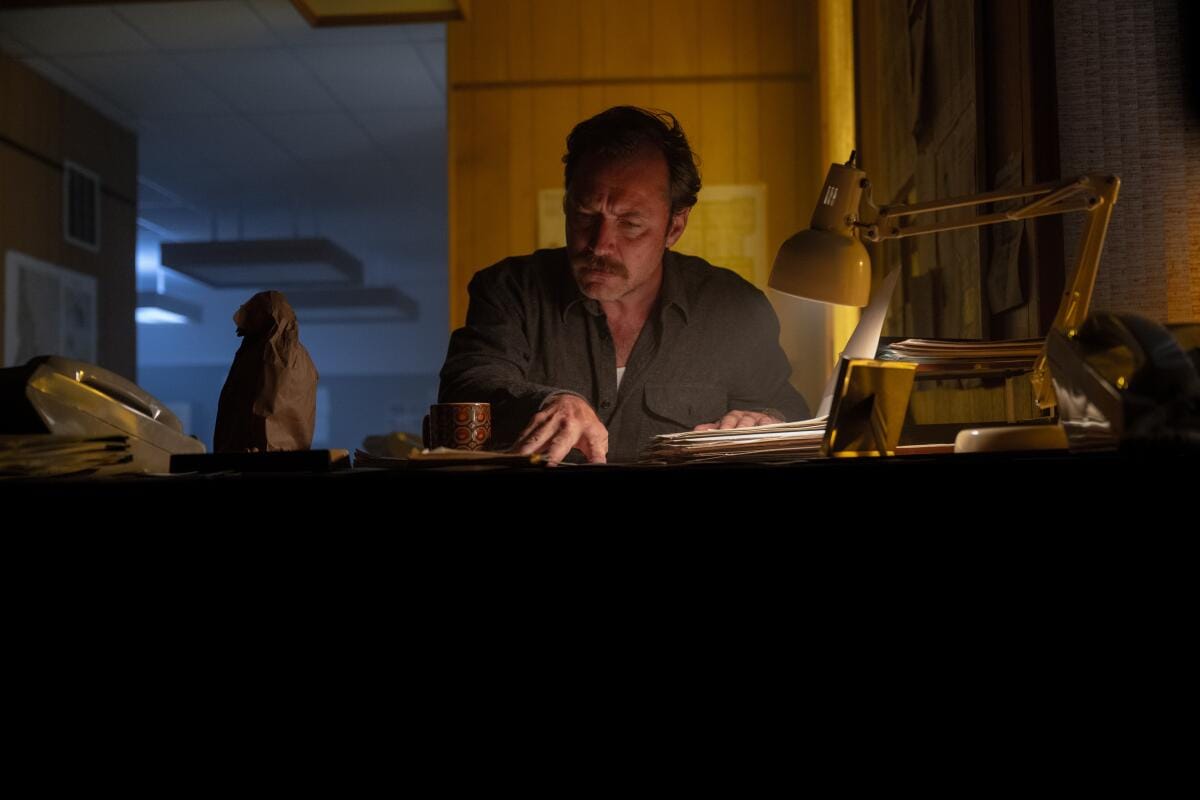

Justin Kurzel's The Order, about the FBI investigation into the increasingly murderous white supremacist terror group of the same name, could have easily fallen into the same trap, but happily it is instead a solid if somewhat undistinguished crime thriller. Starting in 1983 and concluding a little over a year later, it follows an FBI investigator, Terry Husk (Jude Law), who moves to Coeur d'Alene, Idaho in hopes of having a less stressful and draining caseload than when he was busting mobsters in New York City. Those hopes are quickly dashed as he links an Aryan Nations splinter group led by young and charismatic Bob Mathews (Nicholas Hoult) to a string of murders, bombings, and bank robberies that are just prelude to an even bigger attack.

Zach Baylin's meat-and-potatoes screenplay moves crisply through the beats of the investigation, though it has a tendency of jumping forward to just before the next setpiece, which doesn't leave much time to build suspense. Kurzel's direction is likewise not reinventing the wheel but contains some effectively impactful shots. A shrewdly placed camera lends the assassination of Jewish radio shock jock Alan Berg (Marc Maron) a sickening jolt, and several moments, including a creepy initiation ritual, were enough to elicit in me a reflexive disgust.

The movie works as procedural, though at the neglect of its characters. Husk and his partnership with local police deputy Jamie Bowen (Tye Sheridan) touch on some ideas of criminal investigation and how the abyss investigates you, but it doesn't do a lot to push or resolve them. Meanwhile we see how Mathews recruits by preying on the frustrations and insecurities of disaffected young men, but we don't see what's driving him beyond the surface-level explanations; it feels like Hoult's attempt at keeping an indistinctly American accent is holding him back, but it may also be an attempt by the movie to keep Mathews at arms length, to understand him without knowing him.

Indeed when it comes to understanding, the biggest surprise is how much attention the script gives to the theory and practice of this particularly apocalyptic brand of fascism. The racist screed The Turner Diaries is not just casually name-dropped, it is an extremely important plot point and in a way determines the direction of the plot itself. This makes sense given the book's status as an instruction manual for terror attacks, one that would later influence Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and the January 6 rioters. The movie doesn't use footage of those attacks the way Spike Lee did with Charlottesville in BlackkKlansman, but the significance is clear enough.

Perhaps too clear. Streaming rights for The Order were snatched up by Amazon, and toward the end of last year it premiered on Prime everywhere except for the United States, whose Nazi problem incidentally just got a lot worse. It can be rented, of course, and there is no proof that bootlicker Jeff Bezos personally meddled in the distribution plan, but it is certainly conspicuous. Now that we have white supremacists once again trying to take over the country, we'll have to write our own story, hopefully one they won't be so keen to identify with.

Why So Serious

From Darkness to Light

(dir. Michael Lurie and Eric Friedler, 2024)

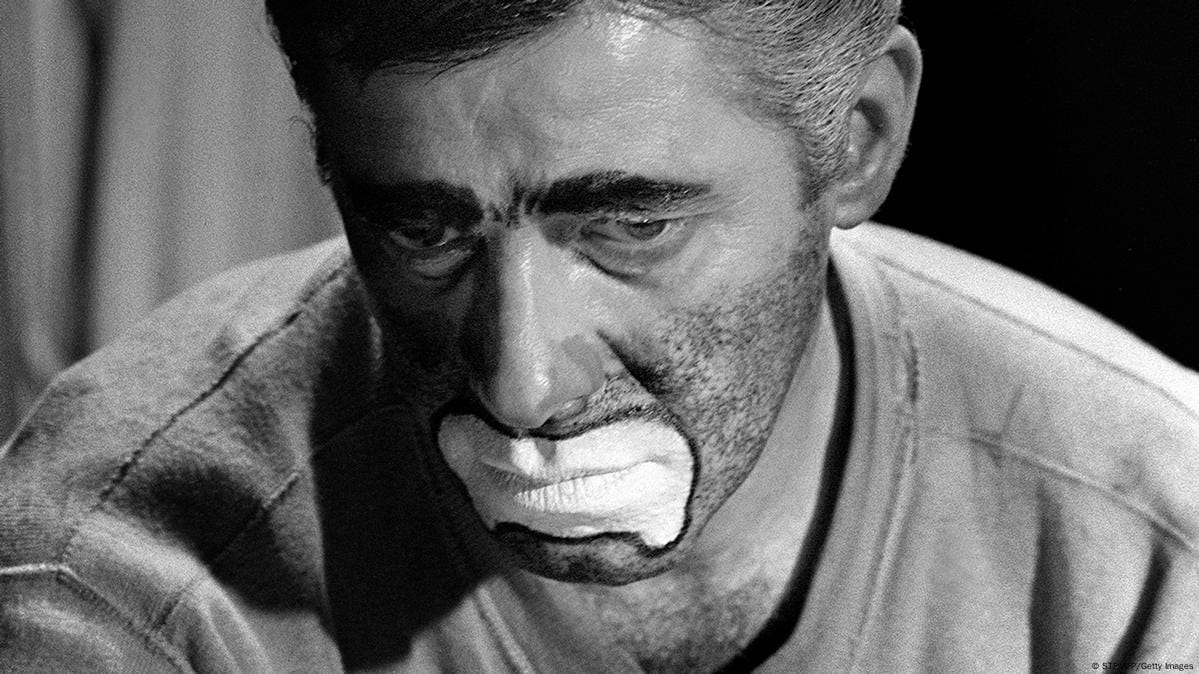

The question of taste and the Nazis becomes even more fraught when it comes to humor. Anyone can make a tasteless Holocaust joke, even not-members of our new government, but is it possible for a film about that darkest of topics to be funny? That was the question surrounding The Day the Clown Cried, Jerry Lewis' 1972 film about a circus clown entertaining children in a Nazi concentration camp. The movie was never released, making it one of the great (as in large) works of lost media, but last year Turner Classic Movies aired From Darkness to Light, a documentary that includes half an hour of footage, the most ever publicly released. Its dual nature, being both explainer and the thing explained, gives it an odd stop-and-go pacing, but that just maintains the fascination of its subject.

The doc walks us through Jerry Lewis' career up to the 1970s, his desire to stretch himself creatively and his struggle to produce his concentration camp clown movie at a time when Holocaust media barely even existed. We get footage of Lewis' film and talk show appearances of the time, re-recorded phone messages from the tumultuous production, as well as interviews with various comedians over the years discussing The Day the Clown Cried and its legendary status. The main talking heads are Lewis himself, still funny and sharp in his twilight years, as well as various figures involved with the production and Harry Shearer, one of the few people who has actually seen something like a full cut of the film. Interspersed with this are lengthy scenes from it in chronological order, enough to give us a sense of its shape and tone.

The doc is most compelling as an examination of Jerry Lewis in an introspective mode. For him The Day the Clown Cried, beyond its broader cultural status, is a personal and creative failure, one that clearly still hurt and haunted him. It's easy to understand, as it is clear he put much of himself into it. The first half of the film is given over to its protagonist, the bafflingly named Helmut Doork, as he is fired from the circus and suffers a crisis of confidence in himself and his purpose in life. Lewis' performance is raw, informed by the insecurities that attend to any creative person and particularly his own doubts about his continued career viability. It's a humane approach to the sad clown type that would take on a more sinister cast in The King of Comedy, where Lewis is the victim of a deluded, disgruntled comedian. The Day the Clown Cried could well have become a part of the 70s canon of thwarted and corrupted strivers if it was just a story of Pagliachian pathos. And it is that—but set in the middle of the Shoah.

I'm still not sure what Lewis thought was the answer to the question of humor in the face of darkness, and indeed in these interviews he seems himself to wonder. At one point he says outright that high-risk work needs to have a clarity of purpose to succeed and that The Day the Clown Cried did not. I don't think that's exactly true. After Helmut is arrested for drunkenly mocking Hitler and shipped to a camp for political prisoners, where he finds a renewed sense of purpose in entertaining the Jewish children fenced off next to them. As one of his fellow inmates tells him, the most threatening thing to a regime built on fear, is laughter.

These are clear ideas, clearly communicated. The problem is they fail in practice. Helmut's clowning, which even the prisoners around him consider bad and not actually funny, is like a whoopee cushion at a funeral, unable to say anything about the solemn proceedings except to imply that they are ripe for disruption. His mockery of the commandant is answered by the immediate murder of one of the other prisoners, and even this understates the Nazis' cruelty. At one point in the documentary one of the Swedish actors playing the commandant says that his character was written to be more understanding than he believed was true to life. Indeed much of the camp footage, centered as it is on Helmut finding his purpose again, feels like middle-class self-actualization with prison camp set dressing.

Lewis seems to think the film's signal failure is that it is in the end not funny, that you come out if it feeling awful. Which goes to show that perhaps trying to find levity in the greatest atrocity in history was a bad idea. It's telling that when the subject of Roberto Benigni's Life is Beautiful inevitably comes up, Lewis is appreciative. That movie covers similar thematic territory, but with a crucial difference: rather than trying to defy a child's predicament, the protagonist denies it, using slapstick to hide the terrible truth from innocent eyes. The idea is faintly risible, as evidenced by the ending of The Day the Clown Cried itself. Helmut ultimately accompanies the children on a train to Auschwitz and continues to entertain them so they are not afraid as they enter the gas chambers. He cannot live with this complicity, however, and, ashamed and guilt-ridden, he chooses to join them. Lewis seems to have regarded this, feeling awful as the children's laughter is cut off by the rattle of a Zyklon B canister, as the movie having gotten away from him. It is the only honest way the film could have ended.

The audiences of 1972 would have probably agreed with Lewis' poor appraisal, which is one part of why it was never released. The other parts have to do with a producer who dropped out and left Lewis holding the bag, and a lapse in the option to the script, leading to a rights snarl no one seems to think is worth untangling. And so we have this attenuated, annotated version if the movie, which is, to be clear, an improvement over mere legend. It is not The Most Offensive Movie Ever that we imagined; it is too aware of the pitfalls it tried to avoid to completely blunder into them. Oftentimes the most off-putting material is the least self-conscious.

The Theater of War And Its Double

Lee

(dir. Ellen Kuras, 2024)

It is strange how we got two war photographer dramas in 2024, stranger still that the first to come out, Alex Garland's Civil War, should be inspired by the same figure as the the subject of the second. Garland merely homaged acclaimed model-turned-celebrated-photographer Lee Miller by naming his protagonist after her, whereas Kate Winslet sought to embody the woman herself in a movie about Miller that she produced. Strangest of all is that, having now seen them both, I ended up liking Civil War more. I didn't like that movie a lot to begin with, but the sensory assault of its firefights and even its irritating pride in apoliticism at least were able to provoke a strong reaction.

Lee is much less frustrating, but its problems are the same that plague most biopics: a dull 'present-day' frame, an unfocused series of true-to-life moments, a flattening of the subject into an uncomplicated hero. It has its strengths: the supporting cast is good (whenever the Metal Gear Solid movie gets made, Otacon needs to be played by Andy Samberg), and Alexandre Desplat's score livens things up with a few left turns, a jazzy riff here, an electronic-sounding beat there. Winslet gives a prickly and irreverent performance that pushes back against lionization, and the best parts of the movie highlight how Lee's impish personality and the stranger parts of her job intersect, particularly a gleefully disrespectful photo shoot in Hitler's bathtub.

Yet I am ambivalent about the meticulously re-staged concentration camp photos (Buchenwald and Dachau, though not identified as such and compressed into one location). Not because the images are shocking, they aren't, not anymore, but because the film's attention to detail in recreating Miller's shots, the biopic compulsion to stage a famous moment because it's famous, borders on exploitatation. It isn't done lightly or disrespectfully, this isn't the gangsters of The Act of Killing boastfully re-living their crimes, but it loses something in the change in context from document to dramatization. Where Miller attempted with her photography to capture the reality of the death camps in front of her, Lee's camera attempts to obscure the reality of a studio production. It is a reconstruction of a document of the real, one considered more successful the better its deceptions. This is true of most historical fiction, and I've felt a similar unease at how The Longest Day turns one of the most deadly battles of World War II into patriotic entertainment. But the discomfort in making real, specific individuals' pain that elicits real empathy into a simulacrum, is here especially acute, the moral urgency of bearing witness becoming just an accomplished performance. 'What a horrible thing they did,' we say on seeing Miller's photos. 'What a great job they did,' on seeing the movie about them.

Lighter Reading

I saw so much in the past couple weeks that I didn't have the space to fit it all in here. I'm still doing some other write-ups, but in the meantime my Letterboxd contains capsule reviews of a 1970s docudrama about the Danes' protection of their Jewish neighbors during World War II, a local screening of Mulholland Drive that was scheduled before David Lynch passed away, and a rewatch of Conclave, one of my favorite movies of last year, whose divisive ending throws down the gauntlet on social liberalism in a way I wish more people appreciated.

Speaking of Lynch, here's one of the best YouTube videos ever:

Welcome to the Rock-Bottom

Come From Away

(dir. Christopher Ashley, originally produced 2017 at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, New York)

Last week the non-Equity production of Come From Away made its way out my way. My mom and I had missed our chance to see it when I still lived in New York, and so I made sure that didn't happen again. It made for an odd artistic time capsule. Ostensibly a performance that is born and dies every night, a traveling musical theater production like this is a recreation of a show that did well on Broadway and could do well abroad. The staging, choreography, and sometimes even an actor or two are all retained as much as possible to bring to audiences the experience as it was when it hit big. In this case that means a show which first opened at San Diego's La Jolla playhouse in 2015 and eventually won the Tony for Best Director for the 2017 Broadway season. Watching it and reliving that time was a bittersweet experience.

Telling the story of the town of Gander, Newfoundland as it landed and housed some 7,000 passengers whose flights were diverted in the wake of the September 11 terror attacks, Come From Away is an agreeably upbeat show. The ensemble focus and Broadway sprechsang style that de-prioritizes rhyming lyrics isn't to my tastes and does make it harder for some numbers to distinguish themselves, but the big choral approach and Gaelic-inflected score has real wall-of-sound appeal. The standout pieces for me are "Prayer," which pulls from the multitude of faiths represented for its lyrics and composition, and the penultimate song "Something's Missing," sung after everyone has gone home and found that they've changed. They inject a bit of reflection and melancholy into an otherwise optimistic show that takes place during the first darkest day of the new American century.

That chin-up attitude feels of a piece of the late Obama years, in a way that had the unintended, unexpected effect of making me feel profoundly sad. The signs of reactionary backlash were there for those paying attention, but the time between the 2012 and 2016 presidential campaigns made it easy to feel like happy times were here again, the arc of the moral universe and all that. A musical that saw the silver lining in the plumes of smoke rising from the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, that found common decency among unimaginable horror, felt like a small victory over despair.

These days despair is in the air, when it is not falling out of it. The performance was held the day after the catastrophic collision of a military Blackhawk helicopter and an American Airlines passenger jet over the Potomac River in Washington, DC which killed everybody on board. Before the show started a message played honoring the victims of the crash. It was a kind gesture; not one that would make a material difference, but an expression of sympathy and connectedness. Such a notion is wholly alien to the current president, who had already blamed the incident on diversity hiring, gutted the agencies created to prevent such disasters, and, when asked by the press if he would visit the crash site, made a joke about them wanting him to go swimming. This is to say nothing of the 25% tariffs he raised against Canada a couple days after the performance, since delayed for a month, as part of a joking-not-joking effort to coerce a century-long ally and neighbor into submitting to annexation.

Come From Away is a necessary antidote to such all-corroding cynicism, a reminder that decent people can make a positive difference in the face of willful destruction. But it is also a reminder of a time, fast receding, when such a view defined the zeitgeist instead of defying it.

Enjoyed the read? Subscribe for free and get the next one as soon as it's published! If you know someone who would enjoy it, share the link. And if you want to support Cinema Purgatorio, any tips I receive will help to offset hosting costs. Any support is appreciated.

Member discussion