The Straight Story: Zen and the Art of Mower (Riding) Maintenance

Greetings! I was too busy to post last week, but had been working on something I was hoping to get up this week. A bout of Covid-19 scuttled those plans and left me too tired and sore to concentrate on anything especially complicated. The subject of today's missive is a lesson in simplicity, however, and the review followed easily after seeing it.

Calling a work of art 'subversive' implies it's getting away with something. There is a value system in place that dictates the rules, and somehow an artist working within those rules manages to make something that feels like it should not exist. The Straight Story, directed by arthouse auteur David Lynch and released by Walt Disney Pictures, certainly sounds like something that shouldn't exist. The movie itself does feel subversive, though for surprising reasons. It's not in the explicit content; the most parentally objectionable aspect is the omnipresence of tobacco products, including a scene where one character uses his cigar to light another's cigarette. Other than that there is nothing depicted that would not be appropriate for kids. But there is so much implied and discussed that children either would not be able to handle or would not even know what to make of, that it becomes hard to believe this is only rated G. The Straight Story isn't so much appropriate for children as it can be superficially understood by them; it is better appreciated the older one is, as it is as great a meditation on aging as they come, regardless of rating.

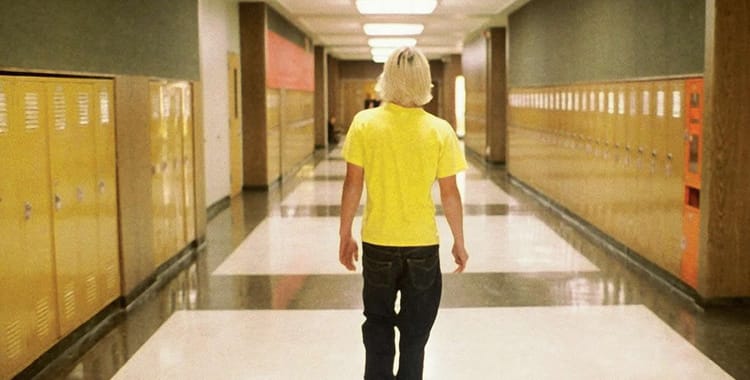

It's easy to see the saccharine, anodyne version of this story just by glancing at its logline, based on a true story: old man rides lawnmower across the country, meeting friendly strangers along the way. It's charming and cute, inoffensive, weightless. Add in a few details, however, and it gets weighty indeed: retired veteran Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth) learns his estranged brother has had a stroke and wishes to see him and make amends. His own declining health—including poor vision, a bum hip he won't obtain X-rays or a walker for, and incipient emphysema for which he refuses to quit smoking—have left him unable to drive a traditional motor vehicle. His mentally impaired daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek) can't drive him either, so he opts to make the 250 mile trip from Laurens, Iowa to Mount Zion, Wisconsin in the only vehicle he can operate, a riding lawnmower. The various people Alvin meets on his journey often have their own baggage, and he helps them as often as he is helped by them.

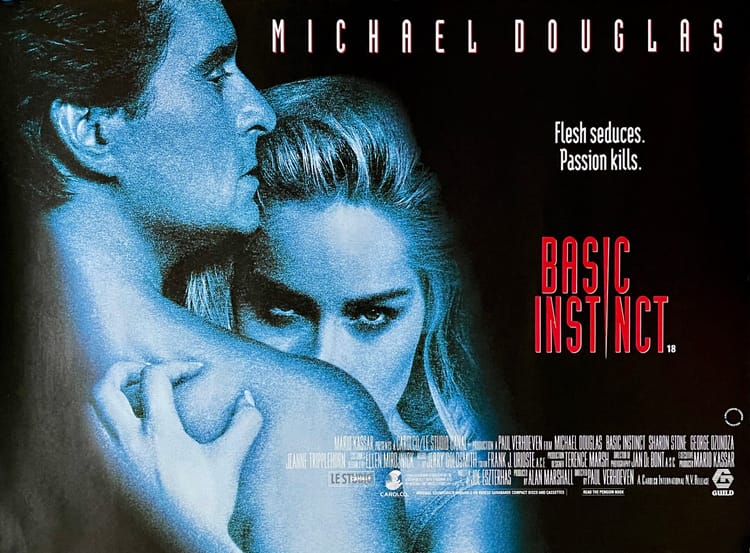

The typical reaction to learning David Lynch made this is surprise and bewilderment, yet it is unmistakably his work. Lynch's penchant for scenes where seemingly nothing happens for minutes at a time is apparent in the very first shot, which concludes with Alvin suffering a fall off-screen and whose prolonged length gives a shock to the next shots, which inform us that Alvin has been on the floor for well over an hour. Lynch's way of making familiar spaces strange is in full display in a brief scene set during a storm, where silhouetted rainfall on a window plays across Alvin and Rose's faces. Many of Lynch's old collaborators are present; Twin Peaks veterans Everett McGill and Harry Dean Stanton, as well as sometime Eraserhead financier Spacek, contribute to the working-class grit that in its own way makes the G-rating all the more surprising. Angelo Badalamenti, Lynch's go-to composer since Blue Velvet, delivers a score that is appropriately warm and inviting without ever being cloying. Lynch's longtime editor and then-wife Mary Sweeney had the initial interest in Alvin Straight's story in the first place and so also co-wrote and produced the picture in addition to editing. Lynch swore off studio films after the Dune debacle, but his work here shows he could still work fruitfully within parameters set by others. (I would be more apt to wonder if his long cinematic silence after 2006's INLAND EMPIRE could have been spent on similar collaborative gigs, but since we ended up with Twin Peaks: The Return anyway I'm not going to ask questions.)

The most overtly Lynchian aspect is the Americana, with the film taking place in Iowa, that most Americonic of states. 'Revealing the unseemly underbelly of Middle America' was practically Lynch's calling card by 1999, and as easy as The Straight Story's premise lends itself to schmaltz, it's just as easy to imagine a misery porn version, albeit not one that would ever actually get made. Yet Lynch as a filmmaker is less cruel than morbidly curious, poking his characters with a stick rather than shivving them with it, and David Foster Wallace once wrote that Lynch is less about evil lying beneath the good than the coexistence of the two in any person and place. The Straight Story isn't as direct about that particular duality—can there be evil in a G picture?—but its tonal balancing act is just as vital, situated between gauzy sentimental idealism and the compromises and disappointments of the real world.

Indeed the road trip structure of the film is engineered, rather brilliantly, to reveal complications, sadness, and hard-won optimism in each deceptively upbeat encounter with a new stranger. A young hitchhiker is revealed to be pregnant, prompting Alvin to disclose some quietly heartbreaking details about his own kids. A drink with another old man leads the two to share stories of World War II combat trauma and guilt that never fully went away. The exception to this is the final encounter, when Alvin finally reaches his destination. It's not much of a spoiler to say the Straight brothers' reunion unfolds elliptically, which is to say, in a Lynchian fashion, highlighting that the journey was always more important than the destination.

The mistake often made when discussing Lynch is to assume his work is only grotesque and random. It's more accurate to say it is dream-like, and more accurate still to say it is rooted in Lynch's embrace of chance and the subconscious. This is reflected as much in those scenes of "slow, go-nowhere moments designed seemingly to do nothing but blank out our minds" as much as the spontaneous creativity that turned a set dresser stuck in a room into a terrifying embodiment of evil, and a failed TV pitch into one of the most acclaimed movies of the 21st century.

That kind of insistent serendipity was present in The Straight Story as well; it was to be Richard Farnsworth's final role before his death a year after its release.[1] Lynch's approach to creativity is about accepting the present and mining the depths of simplicity, and you don't get much simpler than a man and his mower. From that simple setup (tailored for him, it must be said, by the third woman to know him best), he made a movie that without insistence gets at some of life's deepest truths. If David Lynch can do that with a G rating, without a mutant baby or a malevolent force that feeds on pain and sorrow, anyone can.

Farnsworth was in remission for cancer at the time of filming, but ultimately lost the ability to walk after requiring hip surgery and shot himself once the pain became too severe. ↩︎

Member discussion