Old Movies on Getting Older

Tokyo Drift Apart

Tokyo Story

(1953, dir. Yasujirō Ozu)

I'm glad I waited to see Tokyo Story. My local theater showed it as part of their art house series last week, and so rather than on my large but home-sized TV or on my phone (christ), I got to see it on the biggest screen possible, where its small, human-scale drama can assume epic status.

And why shouldn't it? The story of aging couple Shūkichi and Tomi Tirayama (Chishū Ryū and Chieko Higashiyama) visiting their adult children in the big city may unfold in the space of a week, but its narrative threads unspooled years before: eight years ago, when middle son Shōji went missing in the Pacific Theater and his widow Noriko's (Setsuko Hara) obligations to his memory and family became an unsettled question; two decades before that, when their youngest daughter Kyōko (Kyōko Kagawa) was born and it seemed Shūkichi's ugly drinking habit had at last abated; all the years preceding, when each child was born, with hope and promise for what they would become. The sacrifices and betrayals here are the most quotidian, and therefore the most important, for it is in the everyday that relationships are built up and torn down: a day taken off work to spend with the parents, a train missed for lack of urgency. I don't know that I've ever seen something so casually monstrous as when older daughter Shige (Haruko Sugimura) tells one of her salon clients the old couple who just walked in are "just some friends from the country."

The Tirayama children come in varying degrees of selfishness, but the hell of it all is that Yasujirō Ozu doesn't even give us the cold comfort of moral superiority. Such thoughtlessness, we are told by the most thoughtful of all the characters, is inevitable, especially in the post-industrial world. The steam engine and telecommunications collapsed distances to make the world seem smaller, but they also dispersed familial relations into atomized nuclear families, weakening bonds and obligations. Adult children will have their own lives that are increasingly difficult to take time away from, especially when those lives—their everyday—are so far away.

The movie's audiovisual scheme drives this home. Its boxy, ninety-degree angled interior compositions trapping the characters, whose dialogue close-ups are likewise nearly direct-address, giving even generous affirmations an accusatory undercurrent. The outdoor scenes are freer by contrast, but are so open as to strand and isolate the characters if they aren't isolating themselves, as in the famous shot of Tomi watching over her grandson, who plays, unminding, apart from her. Any doubt over what we are to take away from the movie is put to bed by the penultimate scene, underscored with a song, Yube no Kane, which asks, "People of the old days/Where are they now?" and is answered by being sonically obliterated by a train that takes the last and most loyal of the children away and back to the city.

It is a terribly sad film, but not insistently so, nor is it one-sided in its depiction of dissolving relations. Each of the children is given ample time to emerge as a full and contradictory person. Youngest son Keizō (Shirō Ōsaka) is a callow youth but also one who comes to regret his own short-sightedness. Even Shige, who late in the movie acts even more crassly callous, is given shading when she has to handle Shūkichi and a stranger entering her home stinking drunk in the middle of the night. Even though it is largely her fault that he has turned up out of sorts, having turned her parents out for the night, it is still an impossible situation she has to handle.

Death is even more impossible, for there is no rehearsing one's reaction to it. Another reason I am glad to have seen this later rather than sooner is for the life experience I am able to bring with it. All four of my grandparents have passed on, and I now know just how weird and fraught funerals and memorial services can get as everyone most immediately copes with sudden absence. Family drama is often not fiery and confrontational but instead sublimated, passive, oblivious. Tokyo Story quietly but devastingly bears this out. You don't have to burn a bridge to stop crossing it.

L-I-V-I-N, or, Some Minor Insignificant Preamble to Something Else

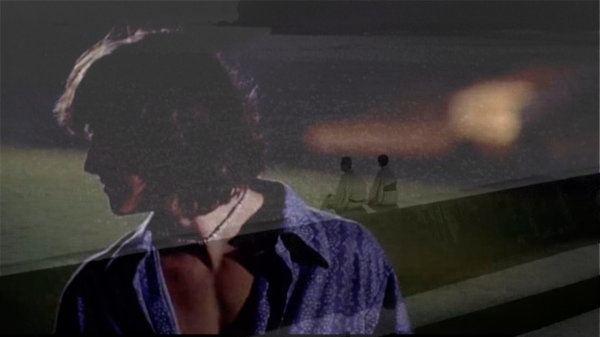

Dazed and Confused

(1993, dir. Richard Linklater)

All art, the meaning of art, changes as we return to it with age, but film is unique for being not just a product of a moment in time but the capturing and preservation of it. Time continues moving forward after the camera has stopped rolling, and so do the camera's subjects. Few have taken advantage of this as much as Richard Linklater, whose Before trilogy along with Boyhood build the real-life aging of their actors into their storytelling, and whose underappreciated 2022 animated feature Apollo 101/2 indelibly captures the talismanic magnetism of televisual memory. Dazed and Confused is more straightforward in its approach to the passage of time; as only Linklater's second film it has to settle with "only" recreating the physical details of 1976 and scoring it with an unassailable collection of period-perfect classic rock. But that just allows it to tap more directly into a sense of memory—not nostalgia, not completely, but retrospection—that because it is already unmoored from the time it was made makes it feel somehow timeless.

What makes Dazed and Confused more than just an exercise in Boomer narcissism (that would be Forrest Gump, which arrived the following year) is the fullness of its view of the first day of summer in the high school population of a small Texas town. High school movies almost by definition include a panoply of competing cliques, but here no single group or individual pulls focus. Senior quarterback Randall "Pink" Floyd (Jason London) is the closest thing the movie has to a protagonist, with the question of whether he will sign his coach's drug-free pledge standing in for his broader ambivalence about the straight and narrow path that's been paved for him. Not incidentally he is the character who most freely floats between the different crowds.

Those crowds are populated by a staggering amount of up-and-coming talent. The charming lech graduate David Wooderson made a star of Matthew McConaughey, and his "Alright alright alright" is one of the movie's most enduring memes. For me, though, the funniest character is easily Rory Cochrane's Slater, whose jittery stoner steals the show with his every moment of screentime. My favorites are "Woodward and Bernstein," Mike and Tony (Adam Goldberg and Anthony Rapp) and Cynthia (Marissa Ribisi), the smart kids who are aware that high school social structure is ridiculous and distasteful but still need to make do while they're stuck in it. The movie lets us inhabit that point of view without ever fully endorsing it, as it does with all of its characters.

The effect of the roving perspective is something of a paradox: it deflates the stakes, but that just makes it funnier that the characters take it seriously. Scenes like the hazing by seniors of the incoming freshmen read less as sadistic cruelty than Bacchanalian anarchy. It's a ritual, a tradition. A stupid tradition to be sure, but a tradition all the same. That consistency gives it a certain amount of fairness; everyone was a freshman once. The only clear villain is Ben Affleck's mean and stupid super-senior Fred, whose relish for inflicting additional humiliation beyond his allotted year is karmically turned back on him by incoming freshman Kramer (Wiley Wiggins), who learns that the high school hierarchy can be scaled by those willling to roll with the punches. Mike learns the same lesson, albeit much more literally, sucker-punching a guy who tried to give him grief earlier. He gets subsequently pummelled, but he maintains his honor. The fact that none of this really matters makes the occasional intrusion of actual stakes and danger—a spectacularly shattered rear windshield, truly reckless driving, and characters who get guns pulled on them twice—feel weird and incongruous, and therefore funnier still.

Irreverent high school party movies are a dimebag a dozen; what makes Dazed and Confused a for-real masterpiece is how it uses this bad behavior to bring its characters to real connection, growth, even moments of transcendence. Tony and freshman girl Sabrina's (Christin Hinojosa) meeting during her initiation, a mock-wedding proposal while covered in hotdog condiments, leads to a tender kiss shared between them at the end of the night. Kramer's big sister Jodi (Michelle Burke) begins to see her little brother as an equal.

Pink's big moment, the one that makes the movie, isn't when he tells his coach off, but just before. As he and his friends laze about the football field's 50 yard line waiting for the sun to come up and he ponders whether to give in and sign the pledge, he off-handedly remarks that "if I ever start referring to these as the best years of my life, remind me to kill myself." It's a funny line, and it expresses the 'adult' perspective, one that recognizes these precedings for what they are, but it's immediately contradicted by his teammate Don (Sasha Jenson), that most jocular of jocks: "All I'm saying is I wanna look back and say that I did it the best I could while I was stuck in this place." It stops Pink in his tracks, and Linklater's camera slowly revolves around him as he takes his in, time itself seeming to stop as Pink considers that most valuable of lessons, to live in the present and not be so fixated on the life yet to come that the life you have passes you by.

Don continues by elaborating that he wants to as have "had as much fun... played as hard... and fucked as many chicks" as he could, while stuck in this place. Pink laughs, we laugh. The moment of profundity is passed, but it elevates the entire movie, which ends on light and frivolous joy, Pink and Wooderson and Slater packed into a pickup truck, cruising down the highway to score some Aerosmith tickets, as Foghat on the radio and soundtrack entreats characters and audience alike to slow ride and take it easy.

That philosophy has served its cast well. The high school setting gives watching Dazed and Confused thirty-one years later extra poignancy. As much fun as it is see McConaughey, Affleck, Parker Posey, Renée Zellweger, and Mila Jovovich so early in their careers, it's edifying to see what became of the performers who did not go on to become stars. Many of them are still working actors today, while others have branched out or pursued other paths. Wiley Wiggins is a digital artist with an MFA from the UCLA Game Lab. Christin Hinojosa left acting and pursued a career in anti-war and social justice activism. Much like a yearbook, the movie captures a moment in the lives of its young subjects, with no indication of where they will go afterward.

It's all too easy in today's era of 'where are they now' legacy requels to imagine a follow-up (Da2ed and Confu2ed). While such a movie could have a similar effect as Linklater's Before films and would easily surpass the original's surprisingly weak box office take, it couldn't reassemble its cast without feeling at least a little beside the point. Wooderson's other immortal maxim, one which comes across more sinister than it used to for being about teen girls, is much more tastefully applied to the appeal of classic films: you get older, they stay the same.

Member discussion