Columbine Media: Traumatis Personae

Hey there. This is going to be a different kind of entry, less focused and more introspective, for obvious reasons. I've gone back and forth on whether to write it, and even then on whether to publish it. It is a deeply unpleasant topic that, I'll explain shortly, put me into a pretty bad headspace. I certainly don't want to inflict on anyone, and I won't hold it against you if you don't want to think about what it is to think about mass shootings and skip this. At the same time, I think my experience is useful in considering what we get out of trying to comprehend the incomprehensible.

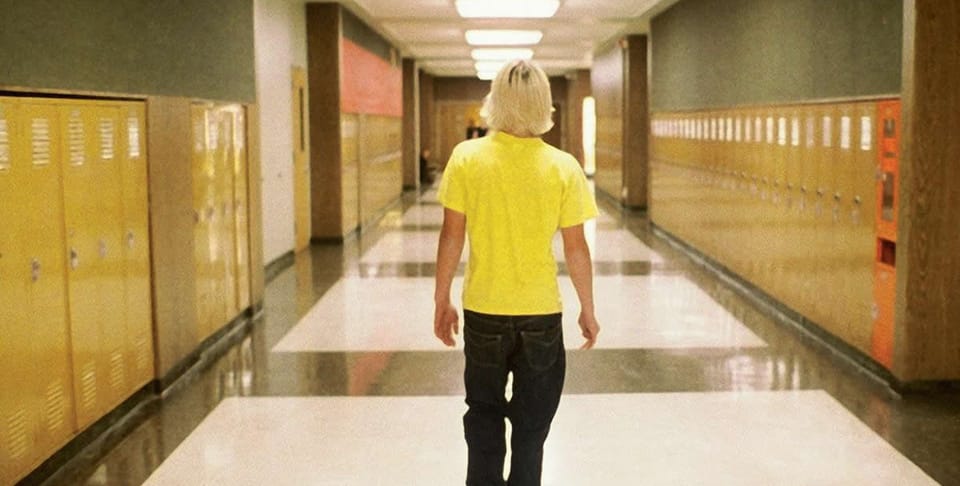

Gus Van Sant's 2003 film and Palme d'or winner Elephant, loosely inspired by the 1999 Columbine High School shooting, is the opposite of a movie about memorable shots. It was conceived to be as spare and naturalistic as possible, with lo-fi cameras filming improvised scenes featuring nonprofessional high school-aged actors. Yet there is a prominently featured Oliver Wendell Holmes quote whose placement seems too appropriate to be an accident. The quote is supposed to be inspirational, but in the context of Columbine it feels like a warning:

Man's mind, stretched to a new idea, never goes back to its original dimension.

Not all ideas are benign. Some are maladaptive, destructive, immoral, evil. Once such notions have been brought into the world, there is no going back; they now exist, and everything that follows is done in the knowledge of them. I experienced this first-hand in the process of considering Columbine and its media afterdeath over its 25th anniversary last weekend. Things that lodge in your brain tend to stay there, for better and worse.

The question that most swirls around Columbine even today is, 'why?' Both 'why did this happen,' and 'why would anyone choose to think about this, much less create something from it?'

The second question is, somehow, the easier. The shooting has been an interest of mine for uncomfortably personal reasons ever since it happened. In my teen years defiance and shock were part of how I formed my identity. I was a gay misfit in rural Idaho in the 90's, and deliberate outrage was both fun and empowering. By the time Columbine happened I was in the seventh grade and consuming a steady diet of fashionably transgressive media: Marilyn Manson, The Matrix, Doom (more precisely the Sonic Doom mod for Doom 2). All of these were blamed by politicians like Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman for inspiring the killers. I deeply resented this notion and what it implied about weirdos like me, and it's informed my antipathy toward moral panics ever since. A lot can change in twenty-five years, however, and in the time since Columbine I thought I would see how I, and the world, have changed since I was a sullen teenager. And so over the weekend I took in not just Elephant, but a variety of news and internet media about the shooting.

This is, spoiler alert, a recipe for morbid depression, but I did not see it as such. I've read and written about some bleak subjects over the years. Murderous religious fundamentalists, internet trolls, Objectivists. I was always able to look at these things with some disinterest and surgically pick them apart. Or at least I thought I was. In reality I was an increasingly miserable person for many years, with untreated anxiety and depression. If grim subject matter didn't affect me, it's because I already felt I was in a world of shit.

These days I am generally content, but given those unhappy times I thought myself innoculated from whatever impact Columbine might have on me. So I took it in. I looked into the disturbing internet fandom surrounding the killers. I played the infamous 2005 indie game Super Columbine Massacre RPG!. I watched the TED talk of Susan Klebold, the mother of one of the killers. I watched Elephant. All of which left me by the end of Sunday feeling much worse about a world with spree killers and the people who love them.

If I was doing this five or ten years younger I would have shrugged this off. Young people joke about serious things, or at least they did when I was young, because the lack of life experience makes it seem remote, less real. I have thankfully never been caught in a mass shooting, but there was a report of an active shooter, later revealed as a hoax, at my school while I was getting my MFA. I have dealt with people who could realistically have become a threat to themselves and others. My own mental health got worse before it got better. After all that, try as I might to maintain some kind of critical distance, the issues of Columbine are no longer abstract. They couldn't help but have an effect on me.

I should be clear that I didn't come away from this thinking any of the things I was reading about or watching were good. I very much did not want to think about them at all. But the mind had been stretched, and even if I did not want to think about them, they were now a part of my background knowledge of the world and what it contains, and that informed my thinking. This was all unconscious, as natural as breathing carbon dioxide, and indeed it corroded my every thought felt like a physical sensation. Imagine a darkness in your peripheral vision that begins to work inward, but instead of what you see, the darkness begins to obscure how you see the world.

This is basically the textbook definition of a trauma response. Which is not optimal for a self-styled critic, someone who digs for meaning, and even less so for an ironist. I find meaning is often best revealed and conveyed in subversion, especially when it comes to disagreeable subjects. It's an analytical trick shot, approaching a subject sidewise to highlight less apparent truths, and a useful tool for navigating a world that will frequently disappoint you. The fact of preachers and pundits that stir up disgust for queer people becomes more tolerable with the knowledge that they will inevitably get caught doing lines of coke off the floor with a rentboy while wearing a dog harness. Irony is a coping device, and I am loathe to admit that there were some things with which it could not cope.

Every approach has its limits, though, and irony is helpless in erecting a mental defense against the reality of a nihilistic death drive. But so too is sincerity. Another person's desire to die and take as many people with them as possible is so overwhelming to any kind of rational response that it is effectively a moral black hole, in the true astronomical sense: a mass that inexorably draws in everything surrounding it, from which nothing, not even light, escapes.

This brings us back to that first question, the 'why.' Friend of the newsletter Dan Stalcup recently wrote a penetrating review of Dennis Villeneuve's Polytechnique, about a 1989 shooting at a Montreal school bearing that name, that was shaped by his own experience of losing friends and one of his professors in the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting. His broader conclusions about the desire for movies to "solve" a shooter's mindset were not far from my mind as I tried to purge it of Columbine's second-order toxicity:

Mass shootings like Virginia Tech and the Montreal massacre occur when people who are so poisoned and broken they have lost touch with reality and humanity get access to guns. Until large-scale systemic and societal change is implemented to address the underlying poison and breaking, it’s basically that simple and that impenetrable.

When we try to apply any explanation or meaning to a specific shooting beyond that, we dignify the senseless violence as an act of personal expression, even if we don’t mean to. It’s a tempting path to go down — to try and make sense of the demons haunting a broken soul so we can exorcise them, to capture them in print or on celluloid. But the end of that path reveals nothing but chaos and emptiness.

This week's post isn't really a review or analysis of anything I watched last weekend, but I do think Dan's point was borne out. As much as I appreciate how Super Columbine Massacre RPG! tries to contextualize Columbine within the alternative zeitgeist that was blamed for it, its attempts to try to understand the shooters is defeated at every step by their ugly callousness and bottomless self-regard.[1] Elephant fares much better by refusing to provide any kind of definitive explanation or even catharsis; it can only try to depict what happened as honestly as it can and let that speak for itself. It doesn't look or behave like a prestige masterpiece, it is nobody's favorite film, but if we were going to get The Columbine Movie, I can think of little that could be done to improve on it.

If artistic attempts to reckon with a shooter's mind are bound to fail, then criticism must be close behind, no? What did I actually get out of consuming so much negativity last weekend? More than one would think. I have a better understanding of myself, my values and limits. It was foolish and not a little arrogant to think I could stare into the abyss without it staring back. The subject defeated me, but it defeats everyone. There is no objectively right way to engage with it. Not everybody cared for Van Sant's austere art house approach, and SCMRPG developer Danny Ledone was still suffering professional consequences a decade after he released his willfully flippant game. Susan Klebold has been lauded for publicly speaking out about her son's actions, but her other son Bryan and husband Tom were against it and she and Tom divorced in 2014. All anybody can do is their best and live with the outcome.

For myself, that means following my interests and curiosity wherever they may follow. Which doesn't mean wallowing in ugliness and cruelty. Taking in the worst aspects of humanity to reinforce one's already negative opinion of it borders on self-harm, and I am not going to make a habit of writing about an actual American domestic war zone the week after covering an imagined one. But if I am taken to cover less savory subject matter, I can only face it, albeit honestly and modestly. The mind cannot return to its original dimensions when stretched to a new idea, but neither can it remain in brittle distension. It must grow; the where is up to each of us.

Unfortunately this particular missive isn't the best place to unpack Super Columbine Massacre RPG and its contentious approach, which involves heavy reference of violent movies, music, and games to comment on how they are scapegoated for the actions of disturbed individuals. I will say that the reflexive hostility to the game in 2005 and now stems in part from the mistaken assumption that 'game equals fun' and therefore a Columbine game is making fun of mass murder. This is not true, as the game is deliberately not fun. There is a real and fundamental tension in how games' needing to be enjoyable on some level for a player to continue playing potentially limits their ability to address difficult topics. But making a game to address a serious topic is no more inherently wrong than writing a play about it; even the terminology is the same. ↩︎

Member discussion