Music and Morality

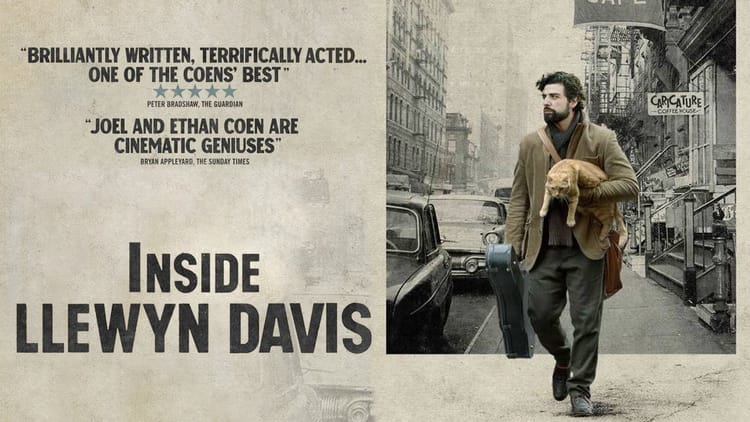

I had so much to say about Inside Llewyn Davis that I couldn't fit it into one oversized essay. For those who also can't get enough of the Coens' musical odyssey, here's a look at how its moral universe is well in keeping with the rest of their work.

Inside Llewyn Davis would seem an outlier in the Coen Brothers’ filmography. Neither a quirky comedy nor a genre pastiche, its most similar siblings are 2009’s A Serious Man, a morbidly funny Job parable set in a 1960s Jewish suburb of Minneapolis not unlike where the the Coens grew up; and their early-career art house nightmare Barton Fink, about a 1940s New York playwright who goes to Los Angeles to write a wrestling picture and develops a hellish case of writer’s block. The period settings, the dry comic tone, the suggestions of autobiography, all make these natural companion pieces.

Yet if there is one common thread that unites the Coens’ impressive tapestry of films, it is that they all, to one extent or another, are about plans gone horribly awry. A great many of these are get-rich quick schemes, often involving a briefcase of cash, as in Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country For Old Men, and Hail, Caesar! Other times it’s a more personal reward: the kidnapped baby in Raising Arizona or Mattie avenging her parents in True Grit.

This consistent narrative framework brings with it consistent moral implications. The characters of a Coen Brothers movie who tend to keep their lives and their dignity, are the ones who know their place in the world. Marge Gunderson is the hero of Fargo not for her righteousness but her competence, and Jerry Lundegaard is its villain because he could not accept his perfectly boring middle-class life—just existing—and contrived to change it in the most underhanded way possible. Hail, Caesar!’s singing cowboy Hobie Doyle is likewise smart enough to know he is out of place in a sophisticated costume drama with dialogue like "Would that it were so simple," but he gives it his best shot all the same. It all works out in the end, and his natural intelligence leads him to finding dim bulb actor Baird Whitlock, who had been kidnapped by a group of Hollywood Communists. Sheriff Ed Tom Bell makes it out of No Country For Old Men alive and physically unscathed because he knew when he was outmatched and withdrew, while Llewelyn Moss’s fate was sealed as soon as took a suitcase full of money from the site of a massacre and thought he could avoid ending up like its previous owner. Llewyn Davis’s aims are much more modest—to succeed on his own terms, without compromise—but he is just as foolhardy.

We see this, or rather hear it, in the most deceptively inviting quality of Inside Llewyn Davis: its music. The Coen Brothers had integrated musical sequences into their movies before—the soundtrack for O Brother, Where Art Thou single-handedly spurred a mainstream interest in bluegrass—but the music of Llewyn Davis, and Llewyn Davis, is the most crucial to its mood and characterization. The atmosphere of the movie’s grey New York winter setting is gloomy and oppressive; DP Bruno Delbonnel gives the visuals a soft focus that avoids the harshness of Fargo’s blinding sub-zero snowscapes, but he bathes much them in blues and greens, giving them a subdued, arguably depressed mood.

Llewyn’s world is an oppressive one, but every time the characters launch into a musical performance, the effect is transporting. Ambient noise falls away, and the soundtrack is overtaken by vocals and instruments. The moods of the songs vary, some wistful, comic, melancholy; but they always come as a warm reprieve. Llewyn experiences this as much as the audience. Though he spends the movie in a state of increasing agitation and exhaustion, performance gives him an escape. Sometimes it’s simple professionalism, as when performing “Please Mr. Kennedy,” a song he finds inane and ridiculous, but more often it’s a vehicle of plaintive expression or a relaxing escape, as when he strums on the long road trip to Chicago. Music may not be for Llewyn “a joyous expression of the soul,” as Mrs. Gorfein puts it, but it is certainly expressive.

Yet Llewyn’s performances are positioned in the film ambiguously. As a vehicle for dramatic characterization they’re spellbinding. But whether the music is good, is more complicated. Llewyn is a good musician, sure, but is he a good folk musician? Certainly the critics at the time of the movie’s release seemed to think so. Oscar Isaac is an accomplished performer in his own right and brings that to bear in the songs, which he played himself. But praise for the music was not unanimous. Music journalist Greil Marcus found Llewyn/Isaac’s delivery far too polished, stripped of the rough edges and grit that makes folk music compelling. It was inauthentic, a hipster pose. This he attributed to the influence of music director T. Bone Burnett, while Pop Matters’ Kevin Korber pointed to the presence of Marcus Mumford, who by 2013 had found success making hitting-rock-bottom music palatable for the Top 40.

There is something to this line of criticism. Consider the track that opens the film, “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me.” Llewis’ singing leans heavily on personal angst, attacking the lyrics with an intensity and volume that is immediately striking but overwhelms the words themselves. The movie’s visuals, the editing, and Oscar Isaac’s magnetism as a performer make the performance continuously engaging, but while the song’s general vibe makes an impression, the nuances are lost. It becomes much less compelling on the soundtrack album, without the visuals to help shape the performer’s characterization.

Compare that with Dave Van Ronk’s rendition, from his 1968 Folksinger album. Von Ronk’s delivery is equal parts defeated and defiant, often quietly mournful and only later on rallying to hit the decibels that Davis spends most of his performance in. This gives him the space to find the gallows humor of the line, "Wouldn't mind the hanging but the layin' in the grave." The performance is modulated and dynamic, and feels like an actor finding the history implied by the lines rather than playing up their surface-level meaning; it feels like the storytelling that folk music is. Llewis’ version is two-dimensional by comparison. Especially because Dave Van Ronk was a point of inspiration for Inside Llewyn Davis, it’s easy to see why the folk musicians who were there so disliked it.

If Llewyn's performances are flat, is that deliberate, a choice on the part of the Coens? Marcus certainly wasn’t buying that line:

But it’s the Coen brothers! They’re cynical! They’re sarcastic! They’re ironic! It’s supposed to be bad! I don’t think so. I don’t believe T-Bone Burnett set out to produce bad performances of good songs, and I don’t think that Joel and Ethan Coen meant Nolan Strong & The Diablos to show up Davis for the mediocrity that he is or to show up the film critics who are so touched by his music as, again in Agee’s words, “the sort of people who enjoy this sort of decay.”

I’m not so sure. True, the movie doesn’t call attention to Llewyn being outright bad. Nor would its creators, who are always somewhat cagey about discussing their work and who had a soundtrack album to move, be apt to sabotage the music in their music-driven film. But the Coens are extremely canny with how they deploy music. Miller’s Crossing is a gangster pastiche with an opaquely-motivated protagonist and all its characters speaking in an alienating made-up argot; Fargo is a story of how the superficial pleasantry of Minnesota Nice can obscure petty moral rot as well as perceptive intelligence. Carter Burwell’s themes for these movies are gorgeous and magisterial compositions, which makes them wildly incongruous. It creates an frisson of audiovisual tension and exchange, the music travestied and the nasty-minded stories ennobled. It’s possible the music of Inside Llewyn Davis was directed to produce a similar friction, not bad but wrong.

Beyond extra-textual considerations, however, there is plenty in the movie itself to support the idea that Llewyn is wanting as a folk performer. The narrative pivots on Llewyn’s failure to succeed as a solo musician, after all. His audience in the opening doesn’t sing along, and the ending makes clear he’s literally no Bob Dylan. Marcus’ own review opens with a discussion of Nolan Strong & The Diablos’ cover of “Old MacDonald” that plays on the drive back from Chicago after Llewyn has failed the make-or-break audition. Bud Grossman, the Chicago impresario, says straight up: “I don’t see a lot of money here…. You’re okay, but not great.” He compares Llewyn unfavorably to upstanding Army man Troy Nelson, who is “a good guy” who “connects with people.” Both are solo performers, but Llewyn doesn't connect with others (as has been made abundantly clear by his interactions with every other character in the film), so could never succeed.

Which isn't to say he is bad. Llewyn's partnership with Mike is fondly regarded, and he is at least good enough that Grossman offers him a spot on a trio he's putting together. But whether out of stubbornness, an inability to enter another musical partnership after Mike's suicide, or simple weary surrender to his fate, Llewyn declines the offer and returns to New York. The moment isn't emphasized, but it is pivotal. Like Llewelyn Moss he turns down a deal to give up his impossible plan and goes on, thinking that God’s not going to cut him down, only to be blind-sided when The Man comes calling.

In the end Llewyn isn't even allowed to fail completely. He is simply to remain stuck in an ennervating loop of couch surfing and missed opportunities indefinitely. It's perhaps not fair, no more than the cosmic fucking-over that A Serious Man's Larry Gopnik receives for thinking he doesn't deserve to get fucked over. But then the Coen Brothers have choice words for those who complain that it's not fair. Like so many other Coens characters, Llewyn puts on airs and pays dearly for it. Should the price less severe? Would that it were so simple.

Member discussion